Earlier this week I came across a blog post casting doubt on the inspirational story of Mormon pioneer John Rowe Moyle (1808-1889). The story has been told in general conference by two different apostles, is in a current church manual, and was even dramatized in a 2008 short film, Only a Stonecutter, by T. C. Christensen of 17 Miracles fame. I mean, who can pass up a story about a pioneer amputee with a wooden prosthetic leg walking 20+ miles from his home in Alpine, Utah, to the Salt Lake Temple and climbing scaffolding a hundred feet high to engrave the words, “Holiness to Lord”?

So what did that post at the 116 Pages blog criticize? The distance. The primary manual says 20 miles, a Deseret News article says 22 miles, and Google says 26.3 miles. Well, which is it people?! Ultimately, the story of an old guy walking that distance in 6 hours (on a wooden leg, no less!) is just too unbelievable. So we shouldn’t believe it.

John Moyle was born in 1808. He turned 77 years old in 1885. Not only is it extremely unlikely that a 77 year old with a crude peg leg could walk 26 miles, it is even stranger that nobody thought to loan him a horse or buggy or that the LDS church didn’t provide transportation for him. By 1872 (15 years before his peg-leg adventure) there was a railroad going from Lehi to Salt Lake City. Source Why didn’t he walk the 8 miles from Alpine to Lehi and catch the train?

Okay. First, inspirational stories are about beating the odds, so unrealistic is often part of the package. Second, this blogger actually had some good material (like mentioning the mountainous walking route and the railroad link), but the presentation was thoroughly underwhelming. I dismissed it at first.

But… the post piqued my curiosity about this pioneer tale. After looking into it, I did, indeed, find some historical inconsistencies. So I decided to do some of my own debunking, Wheat & Tares style.

Story Origins

The first time this story was shared in general conference was in April 2000 by Elder Jeffrey R. Holland (I know, Elder Holland hasn’t had good luck with stories, lately). Elder Holland said,[1]

One other account from those early, faithful builders of modern Zion. John R. Moyle lived in Alpine, Utah, about 22 miles as the crow flies to the Salt Lake Temple, where he was the chief superintendent of masonry during its construction. To make certain he was always at work by 8 o’clock, Brother Moyle would start walking about 2 A.M. on Monday mornings. He would finish his work week at 5 P.M. on Friday and then start the walk home, arriving there shortly before midnight. Each week he would repeat that schedule for the entire time he served on the construction of the temple.

Once when he was home on the weekend, one of his cows bolted during milking and kicked Brother Moyle in the leg, shattering the bone just below the knee. With no better medical help than they had in such rural circumstances, his family and friends took a door off the hinges and strapped him onto that makeshift operating table. They then took the bucksaw they had been using to cut branches from a nearby tree and amputated his leg just a few inches below the knee. When against all medical likelihood the leg finally started to heal, Brother Moyle took a piece of wood and carved an artificial leg. First he walked in the house. Then he walked around the yard. Finally he ventured out about his property. When he felt he could stand the pain, he strapped on his leg, walked the 22 miles to the Salt Lake Temple, climbed the scaffolding, and with a chisel in his hand hammered out the declaration “Holiness to the Lord.”8

Looking at the footnote from Elder Holland’s talk, we find his source, Biographies and reminiscences from the James Henry Moyle collection, edited by Gene Sessions (1974). Luckily, there’s a digital copy of this book available via the Family History Library Catalog. In that volume, John R. Moyle’s great-grandson, Theodore Moyle Burton, related two family stories passed down about his ancestor, one of which Holland used as his source.

…While [Moyle] was working on the Salt Lake Temple, he lived in Alpine, Utah… It was his custom to work on his farm Friday night and Saturday after he finished his work in Salt Lake. He would walk out to Alpine from Salt Lake after he had finished his shift of work as a mason on the Temple and would take care of his farm chores and his irrigating, go to his meetings on Sunday and then walk back to Salt Lake City to work on the Temple Monday morning….

…On one of these occasions when he had returned home for the weekend, he was taking care of milking his cow when, perhaps impatiently or with his hands too cold, or being too rough, he hurt the cow and she kicked him and broke his leg. It was a nasty fracture of a compound nature and the bone stuck through the flesh. In those days there was not much that could be done for people in the way of anesthesia even though they decided the only thing they would do under the circumstances was to cut off his leg. The story goes that they gave him a big drink of whiskey and a leaden bullet to bite his teeth on, tied him to a door and then with a bucksaw, sawed off his leg, bound the flesh over the stump and allowed it to heal. It is a wonder he didn’t die of infection, but the Lord blessed him and the would healed over. while it was healing, he got himself a piece of wood and carved out a peg-leg. He fastened some leather to the top of the wood, padded it and fitted it to his leg. As soon as the wound had healed sufficiently, he walked around the farm on that stump until he was able to stand the pain and had formed a callous over the stump. When it had healed, he walked into Salt Lake as was his custom to take up his work, for he had been called as a work missionary on the Temple. And there, the story goes, he climbed up the scaffolding on the east side of the Temple and carved “Holiness to the Lord,” as his contribution to the Temple building.

Mother told me that great grandfather was a very skilled mason, much more skilled than some and hence grandfather, who was then superintendent of the masonry work on the Temple, asked him to carve the stones which made the spiral stone staircases in the corners of the Temple. This required meticulous cutting and couldn’t be trusted to ordinary stone cutters. Mother said this was his major contribution to the construction of the Salt Lake Temple. These are the stories, as I remember them, from family tradition. (p. 201-203)

Historical Problems

There are two big historical inconsistencies in this story, neither of which has anything to do with the distance between Alpine and Salt Lake. The first is how he broke his leg. Blame the cow, right? Unfortunately, a Utah Enquirer newspaper article from when Moyle broke his leg tells a different story.

John Moyle, of Alpine, Crushes His Leg With a Log

Luckily, a Deseret News article filled in details a couple weeks later.

A few days ago, John Moyle, of Alpine, met with a severe accident in Box Elder Cañon, just above Alpine, from which he is confined to his bed. He was getting out some logs when one of them fell on his leg, badly crushing it. He is resting as easily as can be expected. W. Devey, of the same settlement, had one of his horses’ legs badly broken in the same cañon while snaking logs.

So the stories don’t match. Big deal, right? It’s possible he was embarrassed about getting beat up by a cow and publicized a different tale. Possible.

But a second problem is when he broke his leg. In other versions of the story, he broke his leg in 1874 or at the age of 77 (about 1885). That Utah Enquirer blurb about him crushing his leg with a log was published June 12, 1888. The Deseret News article was published June 27, 1888. Unless this guy had a habit of crushing his legs, he wouldn’t have started wearing a prosthetic limb until much later in life, at the age of 80. And since he passed away in February 1889, he only got to wear that wooden leg a maximum of 8 months. Not a lot of time to recover and make a whole bunch of weekly trips to Salt Lake.

But he still could’ve climbed that scaffolding triumphantly and carved the words “Holiness to the Lord” during those few months he had his wooden leg, right? He could’ve… if those words hadn’t already been engraved on the temple several years earlier.

From The Salt Lake Herald on Saturday, September 26, 1885 (accessed via GenealogyBank.com):

The inscription stone has been finally laid in the centre tower of the Temple. It is of white rock, and the inscription is cut into the stone with gilt letters. It reads: “Holiness to the Lord. The House of the Lord, built by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Commenced April 6th, 1853. Completed —–.”

At the time the “Holiness to the Lord” inscription was installed, Moyle was still about three years away from losing his leg. (In case you’re wondering, the completion date was engraved on the inscription stone just prior to the dedication in 1893, four years after Moyle died.)

At the time the “Holiness to the Lord” inscription was installed, Moyle was still about three years away from losing his leg. (In case you’re wondering, the completion date was engraved on the inscription stone just prior to the dedication in 1893, four years after Moyle died.)

But, the Distance…

The original post at 116 Pages focused on the distance issue, and it’s not a bad angle if you dig a bit. The article would’ve benefited from some additional supporting arguments. Instead of just mentioning the actual distance (they put it as 26.3 miles), they could’ve point out that the Google estimate for walking from John Moyle’s home in Alpine (Moyle Park) to the Salt Lake Temple is a little over 9 hours. Or… that some of Moyle’s descendants walked that trail on Memorial Day in 2000, and it took them from 4:30am till 6:00pm to complete (stopping at times for lunch and snacks, of course).[2]

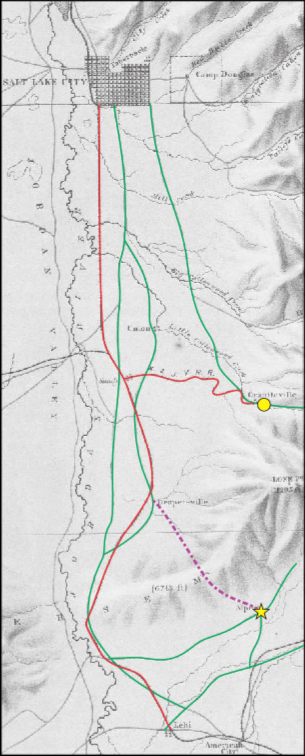

Since I’m a visual person, I also like looking at maps from the time period. Luckily, there’s a good one over at the David Rumsey map collection from 1876 showing the major roads and railway lines. I included it below, highlighting some important parts.

The bright yellow star at the bottom right is Alpine, where Moyle lived. Up top is Salt Lake City. The green lines are the major roadways of that time period, and the red lines are the railroads which became operational around 1872. The yellow circle to the right is the quarry in Little Cottonwood Canyon where granite blocks for the temple were excavated. Moyle likely worked there sometimes in addition to the temple site downtown (it only took Moyle’s descendants six hours to walk from his home to the quarry in 2001[2]). The purple dotted line connecting Alpine with “Draperville” (Draper) is the approximate location of the hiking trail he would’ve used over the mountain. According to the current Google-recommended route, it’s a climb of about 1100 feet before descending into the valley. (As the post over at 116 Pages pointed out, it’s a good mountain biking area.)

Even though Moyle wasn’t walking the route with his wooden foot (it’s unlikely he ever got back to his previous speed during those 8 months before his death), it’s still hard to imagine someone regularly walking from Alpine to Salt Lake City in 6 hours. Oh and by the way, I’m not sure where Elder Holland got the 6-hour time frame in the first place.

But… it’s quite unrealistic to believe he ever walked the whole route. Once Moyle got to Draper, he would’ve been on a MAJOR roadway the rest of the way downtown. No matter what time of day, he’d encounter wagons traveling on that road. And if he was truly a regular, it’s hard to believe no-one was offering “Brother Moyle” a ride on his way to the temple (or on the way home after a long week). Most of the people in Utah at the time were fellow Mormons working hard to create Zion. They would’ve “taken care of their own.”

At the 116 Pages blog (as well as Middle-Aged Mormon Man and Mormanity), the question comes up of why no-one loaned Moyle a horse, or a buggy, or whatever. Something people need to understand about this time period is that the vast majority of 19th-century Mormon pioneers were poor. Really poor. They were building from scratch. Moyle’s family came over in the very first 1856 handcart company, funded by the perpetual emigration fund. He initially started working at the temple to pay back that debt. Now, animals, like horses and mules, weren’t just transportation, they were farm assets. Grabbing a horse to save a couple hours walking to Salt Lake (and then feeding and housing that horse downtown the entire week until it was time to come home) would’ve been an incredibly unwise use of precious farm resources. Walking was a normal mode of transportation (think of 19th-century missionaries). It also provided flexibility that you couldn’t get with a horse or wagon, like being able to hike over a hill rather than taking the long way round.

Conclusion

Mormon pioneer myths are common (I’ve got a bunch in my own family), but they do need to be corrected at some point. Perpetuating these embellished stories does a disservice to both those ancestors and their descendants. John Moyle did break his leg, he did have an ingeniously engineered wooden leg (currently on display at the Daughters of Utah Pioneers Museum if you ever want to take a peek)[3], and he did spend many years of his life working on the temple. But details still matter, especially when you’re using his life as inspiration.

The author of the 116 Pages post wrote, “The problem I have is that the LDS Church cannot help but twist a great story and make into a lie. Either that, or they need to check their facts.” Based on my experience, this seems like a case of believing the family tradition and not checking facts.

Thoughts?

[1] Elder Holland mistakenly said John R. Moyle was the chief superintendent of masonry during the construction of the Salt Lake Temple. It was actually John’s son, James Moyle (1835-1890), who served in a supervisory position. James was “foreman of the builders and stone-cutters on the Temple Block in 1875 and general superintendent of the temple in 1886.”

[2] FamilySearch memory attached to John Rowe Moyle (KWJ1-J6F): “Footnote to the Wooden Leg Story” contributed by BLMV on 12 December 2015.

[3] There’s a good photo of Moyle’s leg at his findagrave.com page. Don’t make the mistake of thinking this is a simple peg-leg.

MaryAnn, you are on a roll of some amazing posts!

Great post! In my ward growing up, my Bishop got obsessed with this story for a while. We watched the movie and talked about the story over and over. Then we actually did the walk from the John Moyle memorial in Alpine to the salt lake temple, starting at midnight. It took us well over 6 hours, (more like 12) and I was amazed that a man with one leg could do it.

Hermeneutic, homiletics, exegesis… all fancy words for providing interpretations, interpolations and elaborations to scripture or historical accounts… resulting of a sort of folklore in many cases. The Jews have embraced these methods with their midrashim which provide “backstories” to scriptural persons and events.

A classic is Abraham in his father’s shop, which sells idols. Abraham demonstrates to his father the absurdity of worshipping the very idols he sculpts. Abraham stages a “riot” among the idols in which he claims that a large idol smashed others in order to take their grain offerings as his own. Terah, upon returning to the shop, refuses to believe the tale. After all, the idols aren’t alive! Abraham catches his father in this logical flaw: Why worship the lifeless work of your own hands?

Maybe it is time for LDS to freely acknowledge and even celebrate our own midrashim… The garden of Eden was in Missouri, Egyptian mummy funeral text yielded the Book of Abraham and so on…

I love this post because I will take truth any day over a fabricated inspirational story. My second take away is to always fact check talks by Elder Holland.

Seems to me the take away is that if we have to rely on fabricated stories to “build faith”, we are a fruitless vestige of Christ’s original restoration.

MH, thanks!

Derekbrimley, I came across a lot of accounts of people doing walks because of this story, either the full Alpine to Salt Lake hike or just the 22-mile route from the Draper temple to the Salt Lake temple. Moyle pushed a handcart over the plains, so he definitely had the ability and determination to walk the full distance if necessary, though I expect it took significantly longer if he ever had the opportunity to do it with his wooden leg. I’m just not wild about people pushing themselves to unnecessary extreme lengths in order to live up to embellished examples of pioneers.

Miguel, fact-checking is always a good idea in my book. Sometimes the truth really is stranger than fiction. Honestly, when I started looking into this, I was expecting to find articles backing up the accounts because they had been repeated so much in different venues. But, based on first-hand accounts from his kids, there’s plenty to admire about this guy without resorting to myth.

Jan, my belief is that there are enough authentic inspirational pioneer stories out there that it’s unnecessary and unwise to rely on fabrications. But, based on my experience with family history, it is not unusual to get these embellished stories because human memory is faulty. That’s why it’s important to verify info in family histories. Passing down fabrications to the next generation is just plain irresponsible if you have the ability to correct the record.

I’m quite impressed by the research skills and tenacity shown here.

The embellishment of the family story is quite familiar. I have heard a number of other family stories which I expect are embellished, but I haven’t actually fact checked them. I have pointed out to family members where I think the facts may be lacking, but the oral traditions continue unabated.

It’s interesting to see the change when the family oral traditions are related in general conference or correlated materials. Like the Sweetwater Rescue, Marsh’s apostasy over milk strippings, and Ryder’s apostasy over a misspelled name, the (almost certainly inaccurate) story will keep being repeated unless a concerted effort is expended to correct it, which seems unlikely.

Well done, Mary Ann! Very interesting.

Did you ever consider the possibility that he broke both legs? It wasn’t unheard of then and it isn’t unheard of now. My brother broke his three different times.

Karl, yes, I did. But then I considered the probability that a newspaper article pointing out he had crushed his leg (not just broken it) would have mentioned that he was an amputee already. The article went to the effort to explain how a horse had been injured in the canyon as well, so it’s not like they were concerned with space.

Also, his obituary (which goes into his life story a bit) doesn’t mention anything about his wooden leg. That makes sense to me if the amputation was a fairly recent event. If the amputation had happened many years prior, I’d think that distinguishing characteristic would’ve been mentioned.

Great sleuthing! But I’m kinda bummed. I liked that story. Next we’ll find out that the cipher in the snow didn’t die and nothing started with Thad.

This is outstanding, Mary Ann. Thanks for doing the digging to figure it out, and sharing it!

I live in Alpine where the John Moyle home is open and available for tours. On a recent visit, the guide told us that he walked to Draper and from there followed a busy road. She insisted that he surely got a ride in a wagon. During the week, he lived with his son, the named supervisor of masonry whose home was in Salt Lake. He then likely hitched another ride or two south to Draper before walking the last bit through Corner Canyon and over a few hills back to Alpine. To be honest, the story of his excommunication over water disputes and taking on a angry second wife are even better stories! Don’t know how accurate those tales are either, but they made for good entertainment for me and a group of Cub Scouts!

Hkgrob, the attempted excommunication one was awesome! That was the other family tradition shared by the great-grandson in the 1974 book. Based on other pioneer stories I’ve heard, I wouldn’t be shocked if it were true. Glad to hear they are pushing the hitch-hiking angle at Moyle Park.

Having lived near Alpine in the 1980’s and as an Australian I was …I think astonished is a good description at Utah culture which was often based on a culture of ‘unicorns and rainbows ‘ a highly romantic culture. This explains, I think not only folklore like this and countless other stories but a very major factor in smothering and distorting so much of church history ( the culture demands ‘positivity ‘ and ‘ niceness ‘ very often at the loss of truth) which has been transported internationally

Do we, as Latter-day Saints, have a way to tell the embellished stores while simultaneously acknowledging that they are stretched beyond historical fact? I’m thinking, of course, of the great American tall tales. I have no qualms about telling them to my children, even though they are based in fact but manage to convince us they’ve been embellished without ever needed to say so explicitly.

Any story experts out there that can pinpoint how we could do that, or whether we have?

Mary Ann, I was the one who wrote the blog post on 116pages.com. I appreciate you taking the story further. It’s sad that this extraordinary man’s life is made into mythology. His true story is very powerful in its own right.

So really this is a non-starter. The argument against the Moyle story is mainly strawman and illogig: it’s tough to believe, so we shouldn’t believe it, since no one mentions that he wasn’t picked up, they’re lying about it, etc., since the dates are wrong (or potentially wrong), the whole story is off.

Facts: a Roman army marched under load 20 miles a day, and then made a camp. The Expert Infantry Badge requires a recipient to march 12 miles, with a 70lb load, in under three hours. People walked a lot in the 1800s. A lot!

Do any of the published accounts tell every detail? No. Do they need to? No.Is there a bit of hagiography going on in the movie? Yes. Does that mean that the whole story is false? No. If Moyle only walked a quarter of the time, and rode the rest, it’s still quite an accomplishment.

If you’re going to pick at details – pick thoroughly, don’t just cherry-pick.

Buddy10mm, the argument is that a newspaper account of him breaking his leg shows he did it years after inscribing the “Holiness to the Lord” stone at the temple. He also was then not traveling with that wooden leg to work at the temple for decades (because he broke his leg within a year of his death). Even without traveling with that wooden leg, he still was not likely to have walked the entire way, due to his route being a major roadway (but if no-one picked him up he could’ve walked it, it just wouldn’t have been with the wooden leg as proven by the timing of the newspaper article).

That in no way takes away from his dedication and hard work. He worked hard, really hard, and his ACTUAL life story is inspirational enough without people having to fudge details for dramatic effect.

So wonderful to have brilliant investigative skills to set these stories straight. Where would we be without your commitment to revealing the truth? We all benefit because you selflessly researched until the true story could be told. Maybe you could help the General Authorities with their talks.

Thanks for the good hearted but clear eyed investigation . I love reading my own pioneer ancestors’ stories, but I ensure I have a large salt shaker near by when I read, since I need many grains of salt.

I appreciate your interest and research into this story. I don’t purport to be an expert historian, but have a nagging question about the 1888 article cited in your report. When John Rowe crossed the plains in 1856, he brought with him his wife and 5 children, the youngest of whom was also named John Rowe and was 5 years old at the time. Could it be, that in 1888, when “John Moyle of Alpine” crushed his leg with a log, that it could have been his son, also named John, who would have been about 37 years old at the time? At that age, he would also have been a well known resident of Alpine, and likely a man in his own right. The thing that puzzles me about the article is that it just says “John Moyle of Alpine”. It doesn’t say anything about him being a mason or associated with the temple or that his leg had been amputated (which would have been an even bigger headline). Acknowledging the coincidence of a hurt leg, citing the 1888 article isn’t conclusive enough to prove beyond reasonable doubt that these weren’t two accidents to two different men named John Moyle. I think, in some way, this allows for the probability that John the Elder could have indeed had a wooden leg for more than 3 years .

Robert Murdock,

“Acknowledging the coincidence of a hurt leg, citing the 1888 article isn’t conclusive enough to prove beyond reasonable doubt that these weren’t two accidents to two different men named John Moyle.” That is a good point, that the newspaper article could be in reference to his son. I would think that the family stories would have noted that two different men named John Moyle each suffered shattered legs in separate accidents, since that’d also make for a fun story. I’d have to look back at the records to see whether the newspapers typically differentiated between the two men. But again, it is a good point that this isn’t an airtight argument.

Well. The leg has been found now, for what that is worth.

I found your post while researching information because my wife and I for years have thought it would be a good reminder for us that sacrifice is worthwhile. So, we are planning to do our own commemorative walk. Your article has provided some interesting concepts to contemplate. At first, it even caused me to feel disappointed. However, even with potential inaccuracies to the original story we still plan to walk 20+ miles to our local temple. Some will ask why? And, others think us foolish. Yet, “this world consists of two sorts of people, those who are acted upon and those who act”. Sacrifice, on any level, helps one learn more about themselves. This type of commemorative effort helps us to understand the types of sacrifices our ancestors made. And, I want my grandchildren to read in my journal about their grandmother and my experience and the emotions we felt as we acted.

From the Berkley Wellness website: “While a brisk walker typically covers a mile in 15 minutes (that’s four miles per hour), a power or speed walker may do a 12-minute mile (five miles per hour), though this depends in part on the person’s height and stride length. A good race walker can move faster than a 10-minute mile (six miles per hour). In contrast, a slow walker or stroller moves at about two miles per hour.”

John could have covered the distance in six hours or less with ease before losing his leg. Thereafter it would have been a challenge.