When I was a kid, my family had a big, beautiful dog of indeterminate breed named Feathers. She was a fun family dog but not really an example of a well-trained animal. We kids thought it was hilarious to have “obedience lessons” in which we would tell our dog, who was already lying down, to “Lie down!” “Stay!” “Don’t do anything!” “Look happy!” Then we would praise her for being such a good girl. Or we would give commands we knew she wanted to follow: “Feathers, come get a treat!” or “Git that squirrel, git it!” She would follow those commands immediately. What an obedient dog! If we told her to do what she was already doing, or to do something she wanted to do, she was perfectly obedient! We thought we were really funny (we were).

But was Feathers really obedient? Or was it just that her natural inclinations had never been challenged?

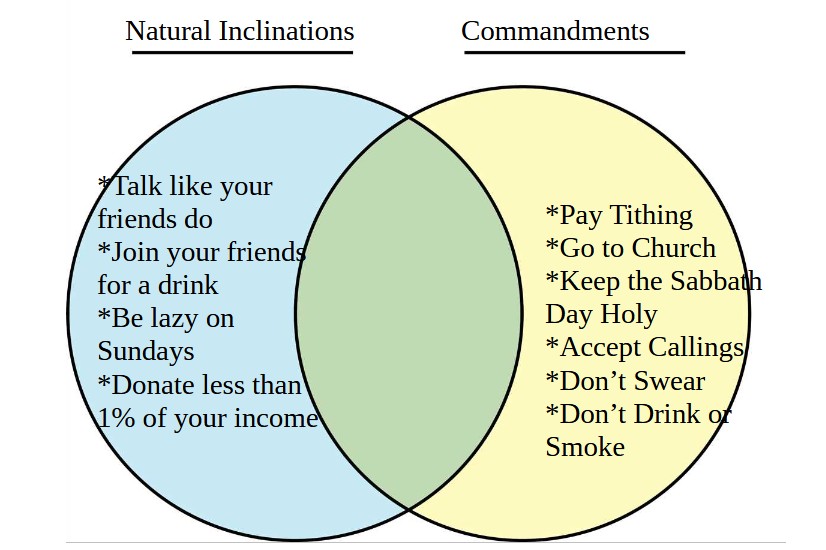

Let’s talk about obedience to the commandments of the Church. What’s the overlap between your natural inclinations and the Church’s commandments? Here’s a handy Venn diagram with some behaviors filled in.

What changes would you make to this diagram to match your natural inclinations? I don’t need a commandment to avoid smoking, for example. Would you go to Church even without a commandment because you like seeing your friends and feel good at Church? Is it easier/harder for you to obey some of these commandments than others?

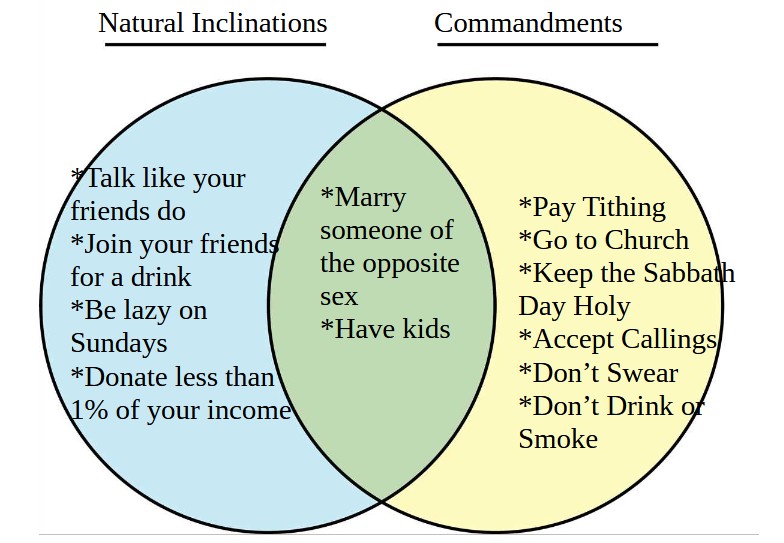

Now let’s fill in that middle section for the majority of the population.

About 7% to 10% of the population identifies as queer, meaning 90% to 93% of the population is heterosexual. It’s hard to find accurate survey numbers, but lots and lots of people want to get married and have kids. If a straight person marries someone of the opposite sex and they have children, do they get righteousness points for that?

We could command Feathers: “don’t have puppies!” and she could comply with that commandment because we got her spayed. On the other hand, if we commanded Feathers to have puppies, she couldn’t do it.

Andrew S. made an insightful comment not long ago on Bishop Bill’s post “Moral Agency” and asked about the impact our inclinations have on our agency and choices. If we want to do something regardless of the commandment, Andrew S. asked if that was really free will. That’s a fascinating question and I hope he does an entire post on it.

Rather than entirely swipe Andrew S.’s question, I’m going to change the question a bit. If we want to do something regardless of the commandment, does it count as obedience? Like, the sort of obedience that gets you to the Celestial Kingdom? Church leaders have taught that obedience is the first law of heaven.

If a straight person presents himself at the Pearly Gates and says, “I married a woman and had kids!” does that help him get into heaven? Or will Saint Peter reply, “You wanted to do that anyway, so heaven doesn’t care about that. You never went to Church because you wanted to go play golf with your friends: go to hell.”

Or let’s talk about another Christlike behavior that is super easy for me because it turns out I have some natural inclinations towards it. I left the Republican party in my 20s because I was sick of the Utah legislature passing laws that made life harder for poor people. Christ commands us to be compassionate towards poor people! Even back when I agreed with the Church’s teachings about sexual behavior, I despised the way the Republicans treated poor people enough to leave the party over it. I won’t sound a trumpet about my alms-giving, but I help. As much as I can, I help. Even though I’ve left the Church and have serious doubts about Christ’s atonement, I help the poor because something inside me wants to help the poor.

So picture me at the Pearly Gates. I tell Saint Peter, “I gave to the poor and helped feed the hungry!” What happens? Does Saint Peter say, “Great job, Janey! Welcome to heaven!” Or does he say, “You wanted to do that anyway, so heaven doesn’t care about that. You divorced your husband because you never wanted to have sex with a man again: go to hell.”

For this discussion, assume that neither the golfer nor myself wants to repent and rely on the atonement for our sin. The golfer has no interest in going to Church. I have no interest in being married to a man.

It’s easier for a naturally social person to fulfill their ministering assignment; introverts with social anxiety are going to struggle. It’s easier for someone who finds it restful to sit quietly to attend Church and the temple; someone with ADHD is going to struggle. It’s easier for someone with upper-middle-class parents to stay out of debt and pay tithing; someone breaking the cycle of intergenerational poverty is going to struggle.

And so forth.

Questions:

- Which commandments are easy and natural for you to follow?

- Which commandments are hardest for you to follow?

- Do you get brownie points in heaven for doing something you have no inclination to do?

- Say you hate public speaking but you accept an invitation to speak in sacrament meeting.

- Say you have Tourette’s and can’t sit quietly in a group but you go to the temple anyway (based on a true story) (the person with Tourette’s ended up hitting a couple people and shouting during the session).

- Say you’re not sexually attracted to your spouse but you have sex anyway, even though you aren’t trying to conceive.

- And the other way around — do you get brownie points in heaven for doing something you want to do anyway?

- The time I went to the bishop and asked if I could teach Gospel Doctrine and he said yes.

- Someone who has always wanted children gets married, has children, and does their best to be a good parent.

- You’ve got young children and would give anything to spend a quiet evening just sitting down. So you leave your kids with your mom and go to the temple.

This is a wonderful post which raises important questions. Is blind obedience worthy of blessings? Does it even deserve praise? The answer is an emphatic “No” to both questions.

Got is not just another Bon Jovi who seeks hordes of croc-wearing followers to mindlessly purchase tickets and scream at concerts. God has a higher purpose.

Followers who can not or do not think for themselves are useless to God. For those mindless followers will be in a real bind when a slight alteration of the common scenario occurs and they have to figure something out.

What is actually beneficial are followers who have been taught, who have given reasoned thought to the teaching, and have decided that following the teaching is the right thing to do. These people will be able to figure things out and do good in any scenario.

Are there blessings for those who reluctantly accept sacrament meeting speaking assignments and put no effort into preparation? Absolutely not! And there is actual harm inflicted on those who have to listen to a talk that is about as energetic as a Soviet-era farm tractor rusting in a field.

And what about the endless ward council, bishopric, and similar meetings in which nothing is accomplished? Do participants get blessings simply for being there? They absolutely do not. And their families are worse off for it because while the parents are in these meetings, the unsupervised children are home playing violent video games while Dua Lipa songs blare in the background.

So many thoughts. It’s a great topic, and one worthy of reflection. I’m not inclined to think that we have a point system of good deeds and bad deeds. In fact, I think the Good Place skewered that notion so perfectly that there isn’t much more to say to that. But I do think being a moral person matters, and that we all have areas where we are naturally more inclined to be moral and other areas where we are less inclined to be moral.

How did we get that way? I suspect a lot of it is through our life experiences–we create neural pathways the more we behave a certain way, and those become easier for us over time. But maybe there’s something related to temperament as well, which could totally be hormones or dopamines. Some people go to the casino and it just lights up their brain in a way that it doesn’t for me. I find it boring, repetitive, noisy and shallow. Some people love the sensation of cliff jumping. I’ve done it, and while it’s not terrifying, the number of seconds I can count falling in the air before I hit the water is not time I actually enjoy. I’d have more fun just swimming and normal diving than doing the more arduous cliff jumping that is so fun to other people. I don’t think those examples are particularly moral, but I suspect that my preferences are related to things like dopamine and hormone levels that differ from person to person and that cause us to engage in risky or more cautious behaviors. Mormons typically associate “goodness” with caution, not with risk-taking. But it’s risk-taking to protect Anne Frank in your attic during the Nazi occupation. It’s cautious to comply with the Gestapo. It’s cautious to tattle on your roommate at BYU, and you get rewarded by the institution. Alex Pretti followed his natural instincts, the same ones that he used as a VA nurse, and helped a woman who was pushed down. Many conservatives said he deserved to be executed for “interfering” with an ICE operation. Was that risk-taking? If so, it appeared to be his natural instinct. Does that mean he also liked cliff jumping and gambling? Not necessarily. There are different types of risks we take.

When I was in high school there was a new girl who had a funny name. I made a terrible joke about her name that stuck, and I felt so bad about it that I went out of my way to befriend her. At the end of senior year we ran into each other and she thanked me profusely for my friendship and for making her life easier at a new school, but she didn’t know that I did both things: made it worse, and then felt bad and made it better.

I was listening to Ezra Klein’s podcast this week about the Epstein files, and the elites who didn’t consider the connection to him to be a deal-breaker, even when they knew what he was up to. There were other elites like Tina Brown who immediately saw him for who he was and refused to associate with him. So was she more moral than they were, or were they just less skilled at judging people? Or were they more transactional (which feels like it is less moral)?

I kind of went off on a tangent here, but in general I do think being a moral person means we work to avoid the social pressures that often lead us to make morally compromised choices, and we learn from it when we fail and do better. We try to remedy the harms we’ve done. Unlike in the point system in the Good Place (where your point totals always ended up in the negative), I tend to think we just have to keep trying to do better.

What is moral has very little to do with the church’s rules, though. Among the ones you listed, most of them don’t make humanity better–they just benefit the church as an institution. Most of those I know who were raised LDS and no longer attend mostly live like Mormons anyway. There are exceptions, meaning some people only behaved as they did because the church prevented them from doing what they wanted. There is often a short-term second adolescence that ex-Mos go through that’s a little embarrassing to watch I guess, but on the whole, I think it’s necessary as you grow up to own your own choices, and if you never have before, well, you have to work that out.

This is the first thing that came to mind reading this thought-provoking post. From Holland’s infamous “musket fire” talk ([link](https://speeches.byu.edu/talks/jeffrey-r-holland/the-second-half-second-century-brigham-young-university/)):

“We have spent hours with them, and we have wept and prayed and wept again in an effort to offer love and hope while keeping the gospel strong and the obedience to commandments evident in every individual life.”

So if obeying commandments you don’t like racks up brownie points in heaven, the Q15 must be racking them up in spades. All that endless weeping and praying as they’re compelled to excommunicate LGBTQ members they’d personally love to keep in the Church — if only Christ would let them! Notice how neatly this frames their obedience as the costly kind — the kind that actually counts.

One can pay tithing, go to church and temple, accept callings, not swear drink or smoke (which are obedience to ceremonial law) and one can still abuse their family members or coworkers, cheat, lie, and harm others, which reflect lack of obedience to moral laws (love God and others). The church obsesses on cermonial obedience, as reflected in the temple recommend interview questions. Jesus focused on moral obedience, ie. Sermon on the Mount. He said very little about ceremonial obedience and sometimes defied it.

From a slightly different perspective–

Is a person who bears three children more moral and more righteous than someone who bears one child?

Is a person who bore seven children a hundred years ago more moral and more righteous than someone who bears three children today?

Is a person whose age at first marriage is 20 more moral or more righteous than someone whose age at first marriage is 30?

Anyway, to the OP’s questions, I think it is worth considering C.S. Lewis’ discussion of Dick Firkins and Miss Bates. God doesn’t consider Dick’s niceness in his favor, and doesn’t hold Miss Bates’ nastiness against her.

“Do not misunderstand me. Of course God regards a nasty nature as a bad and deplorable thing. And, of course, He regards a nice nature as a good thing—good like bread, or sunshine, or water. But these are the good things which He gives and we receive. He created Dick’s sound nerves and good digestion, and there is plenty more where they came from. It costs God nothing, so far as we know, to create nice things: but to convert rebellious wills cost His crucifixion. And because they are wills they can—in nice people just as much as in nasty ones—refuse His request. And then, because that niceness in Dick was merely part of nature, it will all go to pieces in the end. Nature herself will all pass away. Natural causes come together in Dick to make a pleasant psychological pattern, just as they come together in a sunset to make a pleasant pattern of colours. Presently (for that is how nature works) they will fall apart again and the pattern in both cases will disappear. Dick has had the chance to turn (or rather, to allow God to turn) that momentary pattern into the beauty of an eternal spirit: and he has not taken it.”

As I read the OP I kept fighting it. Eventually I realized the entire discussion assumes a transactional framework. I submit that thinking transformation instead of transaction turns the discussion on its side. For example, as a long since transformational thinker, I would ask this kind of question:

“If I resist this inclination/desire/temptation and instead obey that commandment, will it lead to me becoming the person God wants me to be?” Or the person I want to be? The resulting action or choice may or not be the same as in a point scoring system.

Very interesting discussion.

Obedience may indeed by the first law of heaven, but Jesus said the first “great” law of mortality is love.

Maybe we should just leave obedience alone until heaven, and focus on love right now.

I was going to come in on this post and talk up and down about how I’ve been thinking about it a lot, so it’s very timely, and then I saw that you referred back to some comments I had made. 🤗🤗🤗

I was having a discussion with a Catholic a few years back where he was trying to explain that a core part of Catholicism is treating the human being as a subject, instead of an object. And whereas a lot of discussion of “objectification” focuses on external influences on the person, this can also apply to “internal” factors — hence, the human as “subject” should moderate the appetites by self-discipline.

One example my interlocutor used was dieting and exercise vs “technical manipulation” and “medical procedures” — where he asserted that the latter should never become a replacement for the self-discipline needed to moderate one’s det and maintain health. He allowed that surgery could be acceptable to restore the body to proper functioning or to preserve, but that it should not be used to replace self-discipline.

I pressed him on whether conversion therapy — if it actually worked to change someone’s sexual orientation — would therefore be less moral than being tempted and simply choosing not to act on same-sex attractions. After all, the person who is tempted and resists is demonstrating more self-discipline.

He didn’t directly answer that. He said that disciplining appetites isn’t an end in itself, just that the point is to have the spirit rule the flesh, not the other way around so that people do good and avoid evil. And then he said my question was based on a false premise — that Christianity does not make “harder demands, nor different ones, on homosexuals than other people. We are all called upon to self-deny and self-discipline, and to suffer rather than to sin.” So, even heterosexuals have to control their appetites (e.g., if they do not want pregnancy, because Catholicism disallows technical means to avoid pregnancy. If their spouse is sick or injured and cannot have sex for a period of time, etc.,)

I reasserted the question that surely an asexual person would not find it very hard to “self-deny”, and that it still seemed like there was a qualitatively different level of self-denial required for gay people (who can have sex with no one to whom they are attracted at any point in their lives) vs for straight people (who may still need to self-deny to only having sex with one person to whom they are married, and with no one else)…but he didn’t reply back so I don’t know what his followup would have been.

Anyway, I like christiankimball’s comment and way of thinking. Transactional thinking does not interest me, but even when we reframe the question (“If I resist this inclination/desire/temptation and instead obey that commandment, will it lead to me becoming the person God wants me to be?”), I think we can still ask variations of the questions that Janey was contemplating in the opening post.

Is there something about self-denial or resisting temptations that makes a difference in soul development than just naturally aligning to some result? If so, then do people who lack those temptations have less development?

I wrote this post with a transactional view of obedience because that’s the way I lived my life while I was faithful. I was convinced that making myself miserable in pursuit of righteousness would lead to greater blessings, whether that was getting up extra early to read scriptures or taking on a service project that I REALLY didn’t want to do. Things I wanted to do anyway didn’t really “count” towards righteousness in my skewed worldview.

So I’m glad that christiankimball called out the transactionalism. I see life a lot differently now, and I wrestle with re-interpreting my prior actions and beliefs. It’s been interesting to allow myself to like and dislike things, and notice how many ‘righteous’ behaviors are things I would do anyway. On the Venn diagram, I deliberately put a lot of temple-recommend behaviors on the commandments side. Temple recommends are very transactional. As Rose pointed out, Jesus wasn’t concerned with the ceremonial obedience, the transactionalism.

Like hawkgrrl, I think the Good Place totally skewered the idea of righteousness points. Perhaps the Come Follow Me manual could spend four years going through the four seasons of The Good Place. Those episodes are each a discrete little packet of philosophy served up in relatable and memorable stories. Like parables. We should totally study The Good Place in Sunday School. All in favor, please manifest.

Hawkgrrl also brought up social pressure. That’s a great point, actually. Humans are social creatures and what type of morality and moral code do we develop while navigating relationships? I believe our basic temperaments are inborn, but certainly we can choose to grow and stretch ourselves.

mountainclimber — Oh. My. Goodness. That is so insightful. The Q15 claiming they suffer, like they’re the ones who need to be comforted for the agonies they feel as they treat LGBTQ as second class human beings.

Andrew S. – I’m glad you joined the discussion! I’ve been thinking about this topic too, and your comments have really spurred my own thinking. That conversation you relayed, about the value of disciplining appetites, is so thought provoking. Like is it cheating to take Ozempic rather than just white-knuckling the diet in order to lose weight? Do you build character by suffering as you diet? Or do you just spend a whole lot of time and attention on counting calories and making meals into a rigid and unpleasant ordeal? There is a line where self-discipline hits a point of diminishing returns and you’re just making yourself suffer.

I completely second Janey’s semi-serious suggestion that The Good Place be the course of study in next year’s manual and classes. I have never been so uplifted and filled with hope for the eventual purification of humanity with any other experience. The writers did an excellent job of distilling the accumulated wisdom of philosophers and sages and thoughtful contemplaters into an extremely interesting [and amazingly visualized] series.

Janey,

The conversation I had had several years back was pre-GLP1/ozempic, but just from a quick Google, I can see several discussions and blogs from Catholics debating this. And overall, the message seems to be: it’s acceptable for medical necessity, but not when it “become[s] the strategy of first resort, the quick fix that circumvents denial of the flesh, carrying of the Cross, short-term discipline that yields long-term blessings and our need to rely on God to resist temptation: all elements of a Christian walk down the narrow path.”

Overall, I have come away thinking Catholicism is way more “hardcore” than I previously knew, lol.

I guess my challenge is it’s so difficult to really piece out what is medical necessity, what is a disorder that cannot simply be brute forced through willpower alone, and what is the domain of will.

We all recognize that someone with a visible, physical disability cannot simply “will” their way out of that, but so much is invisible and not greatly understood, things like psychology and neurology and hormones and on and on and on.

It feels like Mormonism (and seemingly Catholicism as well) has a vested interest in asserting that willpower is more powerful – this is core to the very notion of us being agents to act and not be acted upon. Every scientific finding that suggests certain things are out of some people’s control threatens the model.

I would like to flip the question on its head.

Is there a lesson to be learned in letting go?

I’m thinking of the serenity prayer:

Is part of the path to spiritual differentiation precisely in developing the wisdom to know for oneself the difference between the things a person can change (and therefore should) to the things a person cannot change (and therefore should not struggle to try something impossible) even if it disagrees with what might hold true for another person or what an institution says?

“It feels like Mormonism (and seemingly Catholicism as well) has a vested interest in asserting that willpower is more powerful” (Andrew S.)

I agree that cultural Mormonism of the twentieth century (my milieu) wants to assert that willpower is more powerful. My grandfather SWK gave me a copy of James Allen’s infamous (my word) As A Man Thinketh when I was 11 or 12 years old as a guide to how to live. I think that’s how he (my grandfather) thought. I think my dad did too.

([From Amazon] “As a Man Thinketh is an essential little volume published in 1902 which explains and promotes the direct connection between our thoughts and our happiness. Do you believe in the power of positive thinking — yet remain unclear as to how that power can be harnessed in your life? James Allen’s As a Man Thinketh explains and promotes the direct connection between what we think and the direction our lives take.”)

As an adult I came to reject the simplistic mind over matter principle. Partly because it just didn’t feel right (intuitive philosophy). Partly that it relies on a mind-body dualism I don’t believe or accept (rational or investigated philosophy). Partly because I became more interested in and drawn to the idea of wholeness. Or, in my words, “Putting it bluntly, the charge here is to grow up. That could be the two-word summary of this whole book: Grow Up.” [shameless book plug]

Even though my path felt more like breaking away from the Mormonism of my childhood, I can glean the idea from modern LDS sources. For example, a quick search at ChurchofJesusChrist.org gets me to a Q&A titled “What did Jesus mean when He said, “Be ye therefore perfect”?” The answer ends with a predictable “we can choose to have faith in Jesus Christ, make covenants, strive to keep God’s commandments, and repent whenever we falter.” I would expect no less. But the development includes this observation, which I take to heart and then jump off on my own: “In the New Testament, the Greek word for perfect means complete, whole, or fully developed, having reached an end-goal.”

Relating this all back to the OP and continuing discussion, when I ask “will it lead to me becoming the person God wants me to be?” I’m thinking of a fully developed, integrated joyful loving moral agent. Your objective function might be different. But I’d suggest that your image of end-goal will make all the difference in how you evaluate that thing you don’t want to do but think you should.

Taking an experiential tack, one afternoon in the mid-1990s I took an afternoon walk along the Charles River, walking from one bridge to the next, across and back again. As I approached the Boston University Bridge coming up the incline to the bridge proper, it occurred to me that big scary projects and challenges were sometimes necessary but the big and scary characteristics were not a good guide to whether to take them on, or not. But the feeling of going up an incline — some effort, not trivial, but perfectly doable with time and patience — had in some abstracted way been associated with everything I had ever done that in retrospect was worth doing. That’s been my integrated-whole-body-mind guide, ever since.

Interesting comments. I especially like the one about how much the GAs “suffer” while condemning gays to hell. If they had any real compassion, they might realize how they add to the suffering.

Social pressure or social customs are an interesting element of morality. In Utah there is social pressure not to drink coffee, or offer coffee to visitors. I noticed when we lived in the south, that if you went next door, they offered you a cup of coffee. It was really nicer, kinder and friendlier than Utah’s “righteous” not drinking coffee. By Mormons being so “righteous” we are actually less kind and neighborly. I never figured out something I could offer my southern neighbors that fit into that social kindness spot.

Another social pressure story. When I was in grade school, I was one of the poor kids from the wrong side of the tracks who was just not well accepted. There was another girl who was also poor, but she also was big for her age and had bad personal hygiene. Well, most of the kids just ignored me. Sometimes I had a friend, often the transient Hispanic kids, and sometimes I didn’t. Well one time when this other girl, we will call her Doris, was in my class, I got sick of the way some of the kids were so mean. They shoved her, called her names, said she had cooties, that kind of cruelty. So, I tried to be nice and be her friend. Instantly, the mean kids started doing the same mean stuff to me. Only worse, because by being nice to this girl, I was taking away their fun. If she had a friend to stand with her, then their cruelty didn’t hurt so much. But after being shoved in the mud, called names, and laughed at, I just could not do it any more. So, when she reached out her hand for me to come stand next to her in lunch line, I just couldn’t do it. I remember the crushed look on her face as I turned away. So, the mean kids went back to just ignoring me.

That isn’t the ending they tell in stories of befriending the kid the bullies are picking on. In the stories they tell in primary, the bullies see someone who is willing to be nice to their target and realize the error of their ways. The bullies never shove the hero in the mud.

Morality is messy. In reality, instead of sweet stories in primary, the bully often wins. In fact, he gets elected president because people like how tough he is, and they think they are less likely to be beaten up by the bully if they follow him and become a bully too.

I have some thoughts on will power and “the easy way out”, but this is long enough, so I will write that up later.

Andrew S bringing up GLP-1 drugs is spot on. It’s not just the Catholics and the Mormons. It’s a real streak among Evangelicals and goes right along with the Protestant work ethic (and part of the DNA of this country) that sacrifice, hard work, etc. are all more moral than doing things the “easy way.” What Ozempic and the other GLP-1 drugs reveal is that if you change the body’s chemistry, you eliminate the desire to eat things that are bad for you. Also, those advocating white-knuckling your way through serial dieting until you die are also overlooking the fact that Americans are eating corn syrup right and left because when farmers had a surplus of corn (used for feeding animals), the solution was to use it in US food instead of the more expensive cane sugar. So we are fat because of government policies outside of our control–capitalism literally made us fatter–and then we are shamed into extremely unpleasant dieting that is an uphill battle given the content of our food. Likewise, there is a pill alcoholics can take (and do, in Europe) that eliminates their interest in drinking alcohol. They take the pill and continue drinking, and their body chemistry changes to the point that the alcohol makes them feel sick (it is a poison, after all). But that drug is not available in the US because here we think everyone has to just use their willpower to fight something we are half-heartedly admitting is a disease. Rather than addressing the body’s chemistry, culturally we think you have to just control things that are either not in your control or for which you are being constantly undermined.

There are some other cultural preferences that the church likes to pretend are “character building,” such as early morning seminary. It’s just an indoctrination factory designed to socially pressure LDS kids into staying in the church (although as I’ve mentioned, it’s where some of the kids in a previous ward I was in developed their coffee habit–thanks to lack of sleep). There are other solutions available that would not require families and kids to disrupt their circadian rythms and jeopardize their grades and mental well being, but nobody want to do those because “we can do hard things.” At some point in the growing up process, we have to come to terms with the fact that sacrifices we’ve been asked to make for basically no reason have not been to our benefit.

When the rules and sacrifices hurt people disproportionately, and when the thing you are giving up is not hurting other people, that’s not righteousness. That’s conformity. That’s the opposite of freedom and moral conscience.

There’s a scene in the book Catch 22 where a group of American soldiers are teasing/tomenting a prostitute. She is bored and disinterested. They want her to say Uncle, which she does without resisting. They are unsatisfied, what they want is for her to play their game, to refuse to say Uncle, then finally give in to their teasing and do as they say. It only counts if she doesn’t want to do it and does it anyway.

I’ve had a thought kicking around my head that, sometimes, the church wants to be the referee in the great race of life, the arbiter of what we can and can’t do in our competition for the celestial kingdom. The story of a great racer who stopped to help an injured competitor only makes sense if you know he really, really wanted to win. But many of us don’t want to win. Many of us aren’t even sure why we’re competing in the first place. The prize (sad heaven) is just not with turning over all our time, talents and energies to the Lord, let alone keeping our sex lives within the bounds the Lord has set.

Oh Janey – this topic could very well define the most persistent personal tension I have. Are there brownie points for “blind obedience”? Short answer, No. Slightly longer, if you are 4 years old and lack the wisdom gained from life experience, then listening to a big person makes some sense. All that being said, here is my diatribe.

Obedience is not an indicator of righteousness; it is a mediator of it.

That distinction clarifies much of the tension between Jesus and the institutional authorities during his mortal ministry. The conflict was never about whether obedience matters. It was about what obedience is for. When obedience is treated as a stand-alone virtue, it quietly replaces righteousness rather than serving it.

Two misunderstandings fuel this confusion.

First is the assumption that obedience possesses moral value in and of itself—that compliance, regardless of outcome, constitutes faithfulness. In this framework, obedience becomes evidence of worthiness, a visible badge of alignment with God. But obedience severed from its purpose is hollow. It can be performed without love, enforced without mercy, and defended even when it contradicts the very life it was meant to protect.

Second is a distortion of the word righteous. Righteousness is often reduced to rule-keeping or moral precision, as though it were a score to be tallied rather than a relationship to be lived. Biblically, righteousness is not primarily about correctness but alignment—right relationship with God, with others, and with reality itself. It is restorative before it is evaluative.

Jesus exposes this confusion repeatedly. When obedience is elevated from mediator to measure, it turns inward and begins to justify itself. Law meant to guide life becomes a system for proving virtue. Faithfulness becomes indistinguishable from control. In such a system, righteousness no longer requires mercy—only consistency.

Jesus does not reject obedience; he rescues it. He restores obedience to its proper role as a servant of life rather than its substitute. Obedience mediates righteousness only when it remains transparent—when it points beyond itself toward love, healing, and participation in the life of God. When it becomes the goal, it ceases to be righteous at all. Furthermore, obedience is inherently relational, not an isolated virtue. Like the cords tethering a skydiver to a parachute, obedience connects two parties—authority and subordinate. It is not morally self-contained; its meaning depends on the integrity of both ends of the tether.

Yet discussions of obedience almost always assume the problem lies with the subordinate. If the skydiver dies, we instinctively blame the jumper. Rarely do we examine the system, the design, or the authority that constructed the parachute. We readily acknowledge that individuals can fail to adhere to laws that protect communal life. But we are far slower to admit that authority can fail—or even abuse its power.

There is abundant warning about disobedience. There is almost none about the misuse of obedience.

Until obedience is recognized as a relational dynamic—capable of distortion not only by rebellion but by coercion—we will continue to confuse compliance with righteousness. And we will miss the deeper call of Jesus: not merely to obey, but to participate in a life where authority itself is accountable to love.

When obedience is used to measure loyalty and allegiance rather than to guide moral action, it ceases to be virtuous. It becomes a tool of conditioning instead of an expression of love. Obedience, untethered from goodness, easily becomes a mechanism for testing devotion. Its focus shifts from what is right to who is in charge. In that shift, the moral center collapses. The question is no longer, “Is this just?” but “Will you comply?” This distortion becomes especially dangerous when sacred stories are reduced to lessons about submission. When narratives in which an authority figure—even God, and perhaps especially God—commands something that appears morally reprehensible are flattened into simple exhortations to “be obedient,” the principle itself is hollowed out. The moral tension in the story is not meant to anesthetize conscience but to awaken it. If the only takeaway is unquestioning compliance, we have transformed a profound moral struggle into a loyalty test.

Obedience that demands the suspension of conscience is not righteousness; it is grooming. It conditions a person to override their moral intuition in order to secure approval. That is not love. Love does not require the silencing of one’s deepest moral knowledge in order to prove allegiance. The day any authority—human or divine—demands that I harm an innocent person to demonstrate loyalty is the day that authority forfeits moral credibility. Trust is not strengthened by coercion; it is strengthened by goodness. Any power that requires violence against the innocent to secure devotion has revealed that it values control more than righteousness.

If obedience is to remain a servant of love, it must always be accountable to the good it claims to protect. Otherwise, it ceases to mediate righteousness and becomes a mechanism of domination.

You lost me right away with this one: “Followers who can not or do not think for themselves are useless to God.” We are children of a loving God. I’m not sure he would refer to any of us as “useless”.