In previous posts, I’ve explored how our relationships with our parents, particularly how we perceive our fathers, colors our perception (projection?) of God’s character in relation to us. Is God a benign or controlling force? Is He involved or distant? The answers people give to these questions often mirror their experiences with their actual parents, recast as divine parents. Just as Genesis says God created man in his own image, male and female, w likewise create God in the image of the familiar.

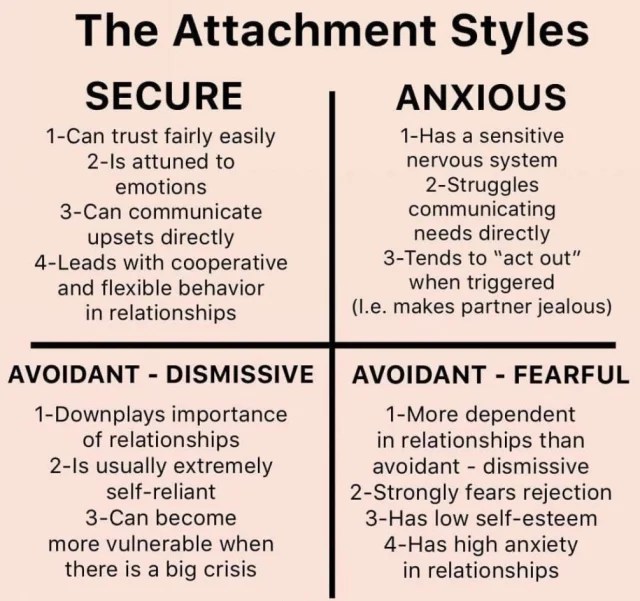

But I ran across a different idea in researching the Zeigarnik effect, which is that the Church as an organization also functions as a sort of parent to those who are raised in it. Like a parent, that can be a supportive, healthy relationship, or it can be unreliable, unpredicable, controlling, or manipulative. In other words, just as our relationship with our parents comes in many varieties, so does one’s individual experience with their church of origin. If you were not raised LDS, but you were raised in a different church, your “attachment style” may have been informed by that experience, just as it is with one’s parents. Here are the four main attachment styles:

The four main styles:

- Secure – “I’m loved and safe; others are reliable.”

- Anxious-preoccupied – “I must work to stay loved; love can be lost.”

- Avoidant-dismissive – “I can’t rely on others; I’ll handle things alone.”

- Disorganized – “Love is both comforting and dangerous.”

These patterns become the emotional template for later relationships — including one’s relationship with God, clergy, or religious community.

For many people, God functions as a primary attachment figure. If you’re having a hard time, you turn to God to fix things and to provide comfort in your time of need. You read scriptures for guidance, taking their counsel to heart as the word of God. Your religious leaders are often there to provide guidance in interpreting the spiritual into your life, and may mediate that relationship with God, although most faiths post-reformation posit that every person has the right to direct access to God, regardless of clergy–to a point. Unfortunately, for LDS people and in many other faiths, if your own perception of God varies with the version leaders preach, you are also told your version is invalid.

So, religion isn’t just belief — it’s a bond. A secure attachment to God feels like peace, meaning, and stability.

But when the faith environment is controlling or conditional, that attachment becomes anxious, avoidant, or disorganized.

When the believer’s attachment figure (God or Church) becomes unsafe — punishing, inconsistent, or rejecting — the spiritual bond breaks down. That rupture feels identical to early attachment wounds experienced in the parent-child relationship. Common messages that trigger this:

- “God loves you — but only if you’re obedient.”

- “You’re worthless without the Church.”

- “Questioning shows lack of faith.”

- “Your doubts offend God.”

The psyche experiences this as divine abandonment. That’s not just theological; it’s somatic — the body registers separation from safety. These types of bonds run deep and come from our earliest age.

If someone separates from their church of origin, how they experience that loss can depend on the way they attached to it in the first place, the experience they had as a believer or insider. For example, based on the four different attachment types, here’s how they might feel when they leave their church of origin:

- Secure. As a believer, they felt “God loves me; I can trust and rely on my Church community.” As a former believer, the loss still hurts, but they will be more equipped to rebuild belonging and meaning.

- Anxious-preoccupied. As a believer, they thought “I must stay faithful to keep God’s love.” When they leave, they will usually experience intense guilt, rumination or fear of punishment.

- Avoidant-dismissive. As insiders, they may have felt “I’ll be good and follow the rules, but I won’t get too emotionally attached.” As doubters, they may abruptly leave and suppress their feelings of grief and loss, but later feel emptiness as the loss of community hits.

- Disorganized. Within the Church, these believers have very destabilizing experiences and may observe “God (or the Church) is both a comfort to me and also hurts me.” When they leave, they usually experience deep ambivalence, both longing and fear, and these are driven by the trauma they experienced while believers.

There are a lot of symptoms for former believers that are linked to “attachment distress,” meaning that relate to their original attachment style that they grew up with inside the Church. Symptoms sound like this:

- Spiritual loneliness: “No one understands what I’ve lost.”

- Existential anxiety: “What if there’s no one watching over me?”

- Hypervigilance or mistrust: “I can’t trust any authority again.”

- Compulsive intellectualizing: Trying to rebuild certainty through information (a way to self-soothe).

- Longing for belonging: Wanting a new “tribe,” but fearing groupthink.

These are specifically attachment responses, not just cognitive dissonance related to one’s belief system. They relate to one’s own sense of security, identity, and social connection to a support system. High demand religions in particular create attachment difficulties by:

- Making love conditional (“God loves you if you obey”).

- Instilling fear of abandonment (excommunication, eternal loss, family loss).

- Replacing internal trust with external authority.

- Creating black-and-white moral frameworks that punish ambiguity.

Getting past some of these views is what constitutes healing and creating wells of internal security that compensate for attachment issues. Some of the steps toward healing include:

- Finding one’s moral center, grounded in what feels authentically right to you, not what others have told you is right. Proving to yourself that you can choose wisely without being told how or what to choose.

- Connecting with people who respect your autonomy as an individual. Creating relationships that are not contingent on your compliance with group norms or another person’s views, that allow you the freedom to live according to your own conscience.

- Reframing your relationship with your past religious attachments in a way that respects your past without letting it define you. Understanding how your past has led to your emtional and moral development as a person, not framed in terms of the external source of some of that learning (e.g. a Church).

- Letting go of fear or anger that leads to overwhelming emotions (e.g. being triggered) when you encounter religious symbols or defensiveness when you encounter believers. Replacing those high-emotion responses with curiosity and love for self and others.

In a nushell, that’s how Church can be like attachment styles. What resonated for you?

- Which attachment style best describes your relationship to the Church growing up (or if you converted as an adult–do any of these resonate)?

- Have you experienced some of these effects of attachment style if you went through doubts or eventually separated?

- How do you handle these issues now?

Discuss.

Yeah, it is certainly the case that mainstream Mormons have a deep attachment to the Church as an institution, but most Mormons have not given any thought to the nature of that attachment. I’m trying to think of other deep attachment scenarios: to the Marines? to teammates on a HS or college football team? to others in a commune-style cult? But those are smaller groups. With Mormons, the attachment is to “the Church.” Maybe do Catholics have a similar relation to the Catholic Church?

Interestingly, there is typically no deep attachment to the ward, your small LDS community where you actually know real people. They become pseudo-friends. It may seem like a strong attachment — but people frequently move, leave the old ward behind with very little difficulty or remorse, and slide right into a new ward in a new town or state, with a new batch of pseudo-friends. So it’s not an attachment to the ward or real people, it’s an attachment to this amorphous entity “the Church.”

Apart from being raised in and socialized to “the Church,” maybe tithing has something to do with this. As an adult, when you have contributed tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars to “the Church” over your lifetime (with no real idea where it goes or what it does, pretty much zero transparency), that creates some sort of buy-in or attachment. If you leave, you’re not just leaving the institution, it may feel like walking away from a huge financial investment.

Dave B: “Maybe do Catholics have a similar relation to the Catholic Church?” I am sure this is the case, particularly when they attend Catholic schools or live in a Parish where everyone is Catholic. However, I would say that my attachment to my ward growing up was very strong, like a large set of parents. I still think of those people as basically aunts and uncles in terms of their status in my life, whether I see them or not, whether they have died or not, and that includes the broader borders into the other ward that shared our building. If that’s not been your experience, I wonder if that’s a byproduct of where I grew up (there were 6 different high schools that fed into my branch, for example, and we had to drive almost 30 miles to church).

I am probably going to be an outlier because, my attachment to the church is avoidant dismissive. Now I am anxious to see what other people say.

And, y’all don’t have to read my psychoanalysis of why I had such a bad attachment because the below is therapy writing.

I always had that feeling of being on my own and unable to rely on church for anything. So, feeling like I had to figure out God/truth on my own and a huge feeling that the church cannot be depended on. That is kind of a surprise. But I guess this is the first time I looked at attachment to the church.

My first memory of church is barely 3 year old me crying because I am alone/lost in my new ward. The memory is very clear and probably repeats the recent trauma I had of being lost in the wilderness above Bear Lake, east side that was very remote 70 years ago. Search party organized out searching and everything, so echoing that trauma would not be good. But church always kind of felt like being lost, the sense of I don’t know where I am or what I am doing.

My ward growing up had a glut of girls and almost no boys. In my age group there were 15 active girls and no active boys. The ward bent over backwards trying to get the two inactive boys to participate and treated us girls like crap. Combined with the older group for Sunday school, there were 30 girls and no teacher was willing to stay more that two weeks. And we were treated like that nightmare was us being unrighteous.

And considering that I have had serious doubts since as young as I can remember, and have never felt accepted by the community, and knowing from very early that I was second class as a girl, maybe that is not so surprising I had a bad attachment. When I think of my reasons for staying with all my doubts, it comes down to my husband being a believer and fear of HIS rejection, has nothing to do with the church really. And I was active, then inactive, then active again, but never good enough all my time in the church. My attempts to be active as an adult always got me blamed and painfully reminded that I was inherently not good enough. (Being blamed as an abuse survivor)

Sure, I kind of decided that church was probably more good than bad, but not *good for me*, just other people. As to can it be depended on, my family was let go hungry during a six month strike at the steel plant. My dad went out of state to find work. The strike was because men were falling into the blast furnace, but the publicity was about the union just being greedy. I remember my mother sitting on the floor bawling because the flour was gone. So, yeah, the church won’t help if you are hungry and barefooted. Our family was specifically not given food because my dad was union. And unions are evil and greedy—no bitterness there.

Leaving felt kind of like when my parents died. But keep in mind that my parents were both abusive. Little bit of grief but huge relief. For my abusive father probably only relief as I had years to grieve for the father I should have had. Sort of mixed for my mother as she was very admirable if you were not a vulnerable child needing a fully functioning parent. So, leaving the church probably more like my father dying- thank goodness that is over. Or why didn’t I do this years ago? (or poison him years ago. Just kidding…maybe)

Alright, my only secure attachment in life is my husband.

So, I want to know other people’s attachment and how it came about.

Dave B: I see a strong distinction between wards with large geographical boundaries and wards with small geographical boundaries. I’ve lived in a town in the Midwest that in the last 50 years has gone from one ward that meets in a building to two wards that meet in that same building. Many of the members have a very deep attachment to the ward(s). So long as you live in that city, you’re still in the family. Currently, I live in suburban Utah and in the last 2 years my ward has had a half dozen families move to a newer, more “prime” location that is literally less than half a mile away. But this is Utah so it is a different ward and different stake. They may as well be 100 miles away.

Secondarily, my experience in the Midwest (in more than one state) was that a significant number of members were Utahns that were far away from family. Our wards spent holidays together. We had memorial day soccer games, and got together at the church to watch fireworks on the 4th of July. (The country club was conveniently across the street!) When we lived out there my family had Thanksgiving dinner with friends nearly every year – sometimes at our house, sometimes at theirs. We once again live in Utah, and most people have family near by, which superceeds their attachment to the ward.

Well color me a bit surprised. It turns out that some people do feel deeply attached to their own little ward. Thanks for the comments, everyone. Perhaps those who grew up in an LDS ward are more likely to develop a deep attachment — especially if their family doesn’t move a time or two and if ward boundaries don’t get rejiggered two or three times. Personally, I joined as a teenager and only had two years in my “home ward” before leaving for BYU, so my period of youth socialization was relatively short. I’m guessing personal experience on this may vary widely.

Getting back to Hawkgrrrl’s post itself, I’m thinking the secure/anxious/avoidant response to “the Church” as a pseudo-parent may be influenced by one’s experience at the local level, particularly with the bishops (the “father of the ward”) that you interact with. I’ve gotta think that if you have a bad interview and a bad relationship with a bishop, it triggers a change in attitude toward a troubled category. If you fly under the radar or are one of the cool kids in the ward, then those responses don’t get triggered.

I’ll echo that I feel deeply attached to my home ward, even though I haven’t been there for more than a decade. It’s hard to have any attachment to any location these days for me because I move around so much for my work every couple years. Home will always be that ward, even if the church that I was a kid and young adult in there is not the church to be found anywhere else now. I don’t know how the Church (big C) gets back that feeling again. I don’t know if society and the church can ever go back to that or recreate something like it. Time will tell.

I see my relationship with the Church and my relationship with my parents as (pretty much) exact mirrors of each other. My parents were dynamic, very active, and had lots of leadership abilities. They took turns having big callings in the ward. I grew up in a ward in which everyone admired my parents and myself and my siblings were expected to also be reliable and show to everything. We were the family that showed up early to set up for the ward activity and left after everything was cleaned up. Every time. (It was fun because this was before you couldn’t have fun in a Church building so we’d peel off from the adults to play hide-and-seek, run races in long empty corridors, or we’d ride around on those carts that were used to store tables and chairs under the stage. Also, working hard with adults was an enjoyable experience; we were part of a team.)

Unfortunately, things at home when it was just the family were emotionally chaotic. In hindsight, I’m fairly sure my father had an undiagnosed and very serious mental illness, and my mother coped by becoming codependent. My attachment to my parents and Church was anything but secure. I recognize elements from all three not-great attachment styles in both my parental relationship and how I related to the Church. While I was a faithful Church member and an exemplary daughter, I was definitely in the Anxious-Preoccupied category. I knew I had to be perfect. Then I fell off the pedestal, and sure enough I was right, if I wasn’t perfect, I had no place in either family or Church. I flipped to Avoidant-Dismissive. I love having friends, but my best friends are people I don’t communicate with more than once or twice a month and see less often than that. I consciously avoid relying on them too much because I don’t want to burn them out.

I believe my relationship with my parents and Church was so similar because my parents were so Churchy and faithful. There wasn’t room to make a separate attachment to the Church; there was no space between my parents and the Church.

As far as home wards go — I was raised in Utah and our ward boundaries changed three or four times growing up. Plus, we had lots of extended family in Utah, and as DaveW mentioned, those family attachments beat out ward attachments. Since becoming an adult, I’ve lived in (pauses to count) at least five wards, not counting all the student wards. My parents moved out of the house where I grew up just after I left for college, which basically severed my connection to the ward members who had watched me grow up. It would have been harder for me to quit Church if I’d quit while living in a ward where I’d been fully active and vital. I quit Church about a year and a half after moving into my current home, and I was only a Primary teacher so I knew only my co-teacher. In previous wards, in which I was a GD teacher or an RS teacher, I had dozens of adult Church friends and strong ties to the people in leadership callings and it would have been a lot harder to quit attending Church from one of those wards.

With my parents, I can see elements of all three of these styles, but probably avoidant-dismissive fits best. My parents were in their 40s when I was born, and they mostly did their own thing while I did my own thing. When it came to the church, though, the messages were clear that you had to work to be loved, more anxious-preoccupied, but eventually I couldn’t accept the things I was supposed to accept, and as soon as I said “no, I won’t take that,” it was weird how quickly the dynamic flipped. Suddenly people were treating me with kid gloves like I had all the power in the relationship. They really don’t want kids to leave the church, even when it’s because they tell you that you have to accept things like polygamy or second class status or whatever, things that are completely unacceptable.

Teenage me kind of scoffed at this farcical switch, and reverted to avoidant-dismissive, but then I had a choice of either not getting a college degree or going to BYU, which was extremely heavy-handed and made me feel very coerced and unhappy. I never really fit in there, but I did learn that you had to go along to get along, which included doing all the things: temple, mission, etc., even if you thought the religion classes were glorified seminary (not a compliment, I assure you), and 90% of the men were undatable due to their unjustified narcissism and sexism. But BYU was really my first experience with Utah church culture (nobody in my home ward was from Utah), and it was a whole different ball game. Very impersonal and coercive.

I was raised in a very conservative, John Birch, family in the 60s. I felt safe at home, and my parents were “liberal” in how they managed their children, allowing them to think for themselves, yet at the same time expressing how they felt about the government, liberty, and freedom. I was also raised in Ohio in a ward that had about half converts from Ohio (my parents being one) and half dentists or accountants from Utah. There was a divide that was very apparent in Testimony meeting when the Utah members talked about the mountains and their own personal family heritage.

What was interesting to me was that while my dad was very John Birch, he was not really active in the church because he smoked and drank and didn’t want to give that up. He was included in ward activities because he was a good speaker and funny, but his John Birch views weren’t really accepted by most members then. During high school, if I wanted to date any member girls, it was usually a girl from outside my ward because there were only two girls in the ward my age, and they seemed more like sisters, which was hard to deal with. So I went to dances a lot and would go with the high councilmen from my ward to other wards if my girlfriend happened to live there. This led to a lot of discussions with these church leaders about my life and family. It was interesting because while they might talk positively about my dad, there was always a “yes, but.” Of course, there was the word of wisdom, but they also talked about his John Birch beliefs and how they didn’t square with the church. I actually had one high councilman tell me not to listen to my father. I briefly considered it, but my dad was a good man, even though his political views were extreme. I think I bought into them myself, not really understanding the big picture, but then I was a teenager.

Ultimately, I went on a mission, got married, got divorced, and moved to Utah, where I began to question a lot of things. I still loved my dad, but I couldn’t handle what he believed pertaining to the John Birch Society. I was also dismayed by how, in Utah, the Conservative attitude gave lip service to serving children, education, women, and caring about the poor; I didn’t see it in any state action. Knowing how many were LDS in the Legislature, I began to weigh my political beliefs and compare and align them to my religious beliefs. Eventually, I started to vote Democratic while calling myself an Independent. I ran for office and even served on a couple of city councils and became very disappointed in how the “liberal” me was treated at church. As a youth, my family was to conservative, but as an adult, after a lot of study and prayer, I was to liberal. It’s interesting to me as well how, following the people I knew from my “home” ward in Ohio, they had changed from being more liberal than my parents to the point of saying I shouldn’t listen to them, to being more conservative MAGA lovers.

Ultimately, I didn’t really feel a part of my home ward or the ward I ended up living in years later. Too conservative for the former and too liberal for the latter. I see the church now as much. more beholden to culture rather than doctrine. They also work hard to foster sameness rather than diversity. Maybe that’s ultimately what a family or even a pseudo-family does.

I have happy memories of the two wards that I remember being a part of growing up. Our ward in Salt Lake was a “newlywed and nearly dead” ward. My dad was made the bishop at age 29. Perhaps it was because I was a BK (bishop’s kid) and the oldest child in my family, but I felt loved by the ward members, especially the older ones. We had a large group of European immigrants in the ward, and they were always bringing us delicious food from their cultural traditions for holidays and for our birthdays. It was a marvelous way to learn about who lived outside of the US. I also credit my dad and his RS president for providing lots of ward dinners, talent shows and bazaars to raise money for the ward budget along with service projects which gave us many opportunities to get well acquainted and enjoy being together. Years after we moved away from this ward my family would return on occasion to visit, and it felt like we had never left.

The ward we next moved into wasn’t quite as friendly as the first one-at least in the beginning. I had begun going through puberty at age 8 and had grown 8” in 4th grade and an additional inch in 5th, 6th and 7th grades. In the old ward this was no big deal because I had always been the tallest child in the primary. In the new ward I was a freak and was taller than all but two priests in Mutual. Thank goodness for one girl my age, because neither of us fit in with the large group of girls our age in primary and then in Mutual. In church you’re so often stuck only doing things with the kids in your age group which made going to church and YW activities unpleasant. Unfortunately, I had no choice about going to church or Mutual. Being able to leave home to go to college was such a relief for me. However, the adults in the ward were generally very supportive and kind to me. In later years when I went to visit my parents and go to church with them I always looked forward to visiting with my older adult friends. It continued this way until we had to move my mom to an assisted living facility nearby her home.

The last ward I belonged to before I left was by far the worst. The bishop treated us as if we were his serfs to order around at will, and there was a dark, unfriendly feeling in the ward. Visitors often commented on the dark aura in the ward. The ward was divided into the uber wealthy who lived in a small gated community and the rest of the ward. All of the leadership callings went to the gated community folks, and they were the only ones who ever spoke in church. Everyone else was ignored. You could tell that the bishop was auditioning for higher callings by the way he acted when higher ups visited the ward. I thought that perhaps I was just imagining the bishop’s behavior and the snobby attitude of the folks in the gated community because I hated going to church. Then a friend who was in the stake RS Presidency called me after church one day and asked me how I honestly felt about the ward. I gave her my unvarnished appraisal of my ward. Rather than being shocked my friend concurred with my own opinion and said that she and the other members of the RS presidency had never been to such a horrible ward. The word “dark” was used frequently as she shared her experience and that of the other three ladies. Out of the mouths of two or three witnesses the truth will be established.

Because of worsening health issues I quit going to church. I didn’t miss them and they didn’t miss me. The pandemic all but destroyed the ward. I had no idea that others were also feeling so unhappy and unwelcome at church. There was a new bishop but he was basically a clone of the one who’d just been released, and the ward members had had enough. For some reason there were a larger than normal number of LGBTQ kids in the ward, and when the bishop went “full Oaks” a large number of parents and siblings joined with their LGBTQ ones and left. From what used to be a congregation of about 350 people the ward is now down to 50-60 attendees. Even those who have been faithful attendees (a couple of my neighbors) are tired of hating Sundays and going to church and are now deciding what to do instead. None of this needed to happen. If you are 40 or older you KNOW that church has changed a great deal and not for the better. Are the Q15 unaware of this problem, do they just not care, or are they living in LaLa Land and remembering the good old days 30 years ago while refusing to do anything substantial to make attending church a positive, uplifting experience? When only a fraction of the ward members still attend and many of those not attending have outright left the church too it’s probably too late to do much to reverse the massive exodus out of the church building and out of the church.