I finally went to see Oppenheimer this week. What I really enjoyed about the film was how many ethical dilemmas were presented for the audience to ponder. There were and are no easy answers. Rather than delving too deeply into these, I thought it would be interesting to tee them up for discussion.

- Is it more ethical to end a war with a single event that might overall save lives on both sides, but will kill tens of thousands (or more) of civilians? Is it ethical to follow the math, or more ethical to let events unfold on their own, even if that additional time will lead to more casualties?

- When using these types of devastating weapons, would it be more ethical to provide ample warning to reduce human casualties, particularly among non-combatants? Or is a higher death toll required to convince an aggressive nation to surrender and prevent further killing?

- Should scientists share information, regardless of nationality, that will either benefit mankind (nuclear power) or that might cause all to agree to a non-proliferation of arms when they see the danger to life on earth?

- Should scientists refuse to create dangerous, possibly planet-destroying weapons because they realize that they will have no control over how those weapons will be used by politicians or others?

- Does war make everyone involved in it unethical eventually?

- Was the arms race and cold war worse for the world than World War II?

- Is the desire for supremacy in the arms race, coupled with a belief in the “rightness” of one’s own nation, sufficient justification for nuclear armament? Don’t all countries feel the same way? Should any country, with the potential for shifting political winds, have the power to destroy the entire world?

- Once the genie is out of the bottle, what can we actually do about it?

- If aggressive, authoritarian regimes are on the verge of gaining advantage in a nuclear arms race, are we obligated to outpace their scientific development to prevent them from taking over the world?

As a child, I remember reading a short story about Nagasaki. The story stayed with me, describing the terrible physical impacts to the citizens who were going about their normal day, unaware that they were about to be bombed out of existence.

In 2013, I finally visited Hiroshima with my family. My kids and I sat at a table, folding origami cranes for peace. We visited the bomb dome ruins and the adjacent park for peace. It was a place for contemplation, for gratitude that we are not living in those times.

I wondered how this film will be received in Japan. When we’ve visited the U.S.S. Arizona memorial in Honolulu, the explanatory placards are written in a politically neutral way so as not to sound too critical of Japan for bombing Pearl Harbor, referring instead to a two-sided conflict that is long ago (and best forgotten, so it would seem). It was a little unsettling to read that right next to the ruins of a battleship that still entombs the remains of thousands of American sailors who weren’t at war until the attack.

When in Japan, we went to the Yasukuni Memorial dedicated to the Kamikaze pilots. The museum lionized the sacrifice of suicide pilots who protected Japanese interests. It didn’t mention the Korean (and other nations’) “comfort women” who were conscripted during war, a system of military-sanctioned rape. War has many casualties.

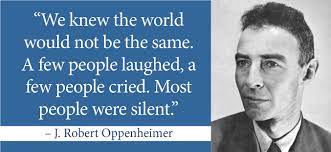

Oppenheimer famously quoted the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” As the scientist who created the atom bomb, he put this power into the hands of politicians. Maybe it was inevitable. Maybe it was important that the slightly better guys got it before the truly bad guys. But we still have this power in underground siloes, and the power is dangerous.

- How has your life been impacted by the cold war?

My father is a WW2 veteran who also worked in the nuclear industry, so these are questions I’ve often thought about. When I was 13, he sat me down to explain nuclear power to me (not, however, nuclear weapons). There are no easy answers to any of these questions (although I personally think we should have stuck with nuclear power as a much cleaner energy alternative rather than scrapping it). What would you have done if you were Oppenheimer?

Discuss.

I don’t really have any answers. There’s a British book “When the Wind Blows” made into an animated film by Raymond Briggs, the same guy who created The Snowman that captures the poignancy of the Cold War and preparations, and nuclear attack. A few years ago we visited a Cold War bunker in the suburbs of York, that is now a museum.

I observe that the nuclear bombings have had a big impact in Japanese anime. I was initially appalled by the extreme destruction and power of explosions in Ghibli films such as Castle in the Sky, and Nausicaa, until I made the connection, which probably took me far longer than it should..

Remarkably for a comic story book, When the Wind Blows was also dramatised on radio: https://youtu.be/OAuqGvVwWKc

The film version appears to be available on streaming services.

We aren’t likely to settle the great debate about the ethics of “The Bomb” here on W&T. Here’s one very simple reason: The Japan of 1945 is nothing like the Japan of 2023.; We can hardly imagine how different Japan was back before 1945. I don’t want to bash the Japanese so I’ll simply say this: Japan has been of the most friendly and dependable allies of the US (and West) in the last 75 years. And we all admire the greatness of Japanese automobiles and electronics. But 1945 Japan was nothing like the Japan we know today. So before you judge those who decided to drop The Bomb, think about the Japan of 1945 that was not going to stop their aggression until they had to.

Josh H: That’s an incredibly important point. In a conversation after the movie, my adult child (who is studying Japanese and has aspirations to live there one day) said the US actions were wrong because of our insistence that the Emperor step down, and that it’s not our decision how other countries are governed. I’m not exactly a WW2 scholar, but I’ve read more and lived longer than my 25-YO, and pointed out that Emperor Hirohito was not going to cease his actions and that he was the one who started the war, to say nothing of his designs on neighboring Asian countries. I completely agree with your point. The world my parents lived in bears little resemblance to the one I grew up in, and we have to avoid presenteeism. IMO, the movie did a great job of making that clear. Decisions always appear different in hindsight, but this one bears scrutiny despite the horrors visited on the citizens of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Oppenheimer always said he would still have done what he did, given the circumstances, even though he knew that the world was no longer the same after this act, and it was much much worse.

When I was living in Singapore, I had oversight for our Tokyo office and was in Japan many times. It is an incredible country, but even today I would say that it is largely inscrutible to westerners. Its values, many of which are probably more deeply moral than ours, are often unfathomable coming from our cultural assumptions.

I haven’t seen the movie, and I confess I’m not excited to buy a ticket because of the way I anticipate the writers/directors blithely portray Los Alamos as a remote, uninhabited wasteland. Or otherwise completely ignore that the actual first fruits of destruction by this inaugural nuclear weapons industry were the people and livestock living nearby, in long-established rural communities, mostly indigenous folks and Hispano-Americans whose families had lived there for many generations. Does the movie give this a reference at all?

Northwestern New Mexico is actually a rather lush part of the high desert southwest with reliable water, and supports ranching and agriculture comparatively well. Los Alamos itself wasn’t the smallest of small towns even before the government brought its interests. The reports that one can find, if one looks into it, are of healthy cattle shot in the head and families turned out of their homes nearest the “test” site, with no recompense. And later, deaths, injuries, and recurrent illness of the rural inhabitants and their children with no aftercare then, either.

If I’m weary of seeing indigenous history so consistently erased from everything, everywhere in America, imagine the weariness of contemporary indigenous Americans experiencing their part of history always being “overlooked.” I’m sick of seeing it, and I’m calling it. There’s no excuse for this in 2023, except raycist ones.

When discussing the ethical concerns of the work wrought by Mr. Oppenheimer and the US Government at Los Alamos in the 1940’s, it’s a pretty conspicuous blindness that’s shown by the creators of the movie, along with the government (always) and the rest of us, to ignore the effects of that action on the local people of rural New Mexico.

My grandfather served in WWII as a Captain in the Army infantry, he had a Purple Heart, a bronze star and a silver star – he was a brave and good man. He served in France and expected to finish his tour in the Pacific but then the war ended…abruptly. He was a gentle person who disliked guns and hunting and who didn’t like to talk about the war, but I remember once he said that they expected a million US casualties while invading mainland Japan. A million young men. He never said whether he approved of the bomb or not but said he was alive because of it.

Interestingly my other grandfather didn’t serve in WWII but was working in Eastern New Mexico and saw a blinding flash of light one summer morning which they said was an enormous ammunition depot explosion. Nobody could really understand what an atomic bomb even meant. There was a deep weariness of the war, and that grandfather who stayed home would relate stories that the Western Union delivery man was the most hated person in town. It’s hard for me to pass judgment on people who wanted peace almost at any price. I’m not sure what decision I’d make.

Applying this question of ethics to my family and on a smaller scale. I’ve worked for a large defense contractor, and 3/4 of my kids are engineers and work for defense contractors making very lethal weapon systems. We’re vaguely uncomfortable with that fact but we also realize that if we and the entire US do our collective civic duty hopefully they will make wise decisions. We understand that “we sleep safely at night because rough men stand ready to visit violence in those who would harm us.” I wish the world didn’t suck so much sometimes.

MDearest: “the actual first fruits of destruction by this inaugural nuclear weapons industry were the people and livestock living nearby, in long-established rural communities, mostly indigenous folks and Hispano-Americans whose families had lived there for many generations. Does the movie give this a reference at all?” Yes and no. I had read up and listened to several podcasts about it beforehand, and I’m getting what was in and what was out a little bit jumbled. I would say the movie didn’t portray the damage, but Oppenheimer specifically said, when the Manhattan project was done, that the land should be given to the tribes who have lived in the area throughout this, that he considered them the rightful heirs, not the government. The government official just looked at him like he was crazy to even suggest such a thing. There may have also been a reference to impacts from the testing, but it wasn’t shown if so.

I really enjoyed this podcast on White Sands National Park, so much that we started looking at making a trip out of it. However, two of the most interesting things mentioned are either inaccessible or hard to access. You can see the actual site of the blast (which includes green glass fragments created from the bomb +white sands, forming an entirely new substance) only once per year if you have a permit. Additionally the podcast explains that early human footprints, dating back 40K years have been found in the park, which is just incredible!

https://www.washingtonpost.com/podcasts/field-trip/white-sands-national-park/

I don’t think the film covered this enough, but given that it was already at 3 hours, I’m not sure how it would have done it justice. Oppenheimer was definitely in sympathy with the locals, especially indigenous people, but that doesn’t mean they were represented.

My grandfather was a WWII vet who later went on to be a security guard at Los Alamos. One could consider him an indirect contributor to the construction of the bomb in more ways than one, since he ended up donating blood to one of the scientists for an operation of some sort. I don’t remember who it was, but my grandpa described the man as generally standoffish, though he showed gratitude to my grandfather.

He told me other stories that I don’t recall reading in the History Books (doesn’t mean they aren’t there now), and probably are better off not being repeated here.

Another thing that stuck out from his stories was how most of these scientists could figure out how to split the atom, but couldn’t use a vending machine to save their lives. I’ve grown more sympathetic of these types of people with time, especially as we’ve become more aware of the spectrum. I’m curious as to whether the movie touched upon that.

I work in an industry with lots of connections to Japan. I’ve heard many stories of Americans going over there and getting thanked by Japanese for keeping things from getting worse by using the Bomb. I haven’t heard of any berating Americans for it, but Japanese strike me as far too polite to do so.

Everything I’ve read and tried hard to think objectively about has ultimately led me to believe it saved more lives in the end, but that doesn’t mean I feel good about it.

I’m in no rush to see the film, but may watch an edited version at some point. I do enjoy Nolan’s work overall.

Eli: I would say that there wasn’t any direct reference to being on the spectrum, but Oppenheimer’s early college life was depicted, and he was one bizarre dude, whether what we traditionally consider to be “on the spectrum” or just a lonely, isolated, awkward genius. However, referring to the spectrum would probably be anacronistic regardless. The movie did not refer to his writing “rape fantasy poetry” or that he watched a couple making out on a train and immediately jumped on the girl when her boyfriend got up to leave. (I got these details from The Rest is History podcast, links here):

https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/343-oppenheimer-the-father-of-the-atom-bomb/id1537788786?i=1000617838413

https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/344-oppenheimer-the-witch-hunt/id1537788786?i=1000617840657

I have not seen the movie yet, but the question about whether or not the Japan of 1945 could have been convinced to surrender via conventional war efforts is interesting. I don’t think they would have. My perspective on pre-1945 Japan is influenced primarily by two experiences: I lived in South Korea for over a year in the mid-90s, and I read Iris Chang’s The Rape of Nanking.

Chang’s description of the Japanese military’s 193os march on the ancient Chinese capital is numbing. (Chang eventually committed suicide and reportedly told a friend that she just could not live with images in her head any longer.) It frames early 2oth century Japan as a highly militaristic culture with delusions of cultural and ethnic superiority that fed an inability to see other nationalities and ethnicities as even human. Some of that lives on today in Japan’s refusal to issue a full apology for wartime atrocities.

Unsurprisingly, 25 years ago the level of animosity in South Korea towards the Japanese was still pretty high. In soju-fueled discussions, my students had no compunction about letting loose with “I hate Japan!” I was not familiar with Korean comfort women until having lived there, but in many ways the nation itself still carries the collective indignity of that historical episode and I think it would take nothing less than a full-scale apology and reparations for a lot of Koreans to move forward.

So, was it the right decision to drop the bombs? Yes, I think so. The Japanese would not have surrendered.

Was it the right decision to build the bomb? Yes, given the scenario. The Nazis were working on a similar project, and there was every expectation that the Soviets would pursue a similar path when able.

Does war make everyone unethical? In all likelihood. Just war theory holds that there are legitimate reasons for war but that there should be boundaries around what is acceptable when fighting a war. But that’s a theory, and practice is much uglier. Curt Lemay’s firebombing of Tokyo would have fallen outside those boundaries, to be sure, but it also served as a measure of Japanese resolve and probably contributed to the belief that only a weapon of terrifying scope and power could end the war in the Pacific. The bomb put Japanese society on a different path. They are probably the only ones who can properly assess whether or not it was worth the cost.

OK people, so the whole dichotomy of “either dropping the bombs or doing a ground invasion” emerged in 1947, after the war. And is in fact, not true. It wasn’t a binary choice, there was another option on the table that didn’t require further violence. But the US didn’t take it, but because they didn’t, they’ve had to retroactively portray it as a Sophie’s Choice type thing.

So I’ll try to summarize this briefly, but there’s a 2 hour and twenty minute video that argues this better and goes into painstaking historical to detail to make the case here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RCRTgtpC-Go if you want to follow this further.

Short answer:

But in sum the atomic bombs were not necessary to get the Japanese to surrender. All the USA had to do was guarantee that Hirohito would keep his head and position as emperor and they would’ve surrender. No bombs or ground invasion necessary.

Long(ish) answer:

Because of the attack on Pearl Harbour, the USA wanted an unconditional surrender from the Japanese. By 1944 it was obvious to the Japanese that they weren’t going to win. But they refused unconditional surrender for two reasons:

1) They hoped to get better surrender terms from the Soviets by offering them Manchuria

2) They were afraid that the Americans would execute the emperor (who has a deity-adjacent status) for war crimes

So they held out and ignored the American’s calls for unconditional surrender because they were hoping to surrender to the Soviets instead and get better terms. However, Stalin had no interest in negotiating with the Japanese, because he figured he could just take Manchuria with minimal resistance after the war in Europe was wrapped up. The Japanese garrison in Manchuria was under-supplied, under-equipped, and had generally low morale. Stalin wouldn’t need to make any concessions to get Manchuria.

When it became clear that the Soviets wouldn’t play ball, the Japanese did send overtures for peace talks to the USA, who in turn, ignored them as they would accept nothing else except unconditional surrender.

The war could have stopped here, they could’ve had a ceasefire, there could’ve been peace-talks, the Japanese tried for better terms but would’ve settled for the single condition of letting the emperor live. And the war could’ve ended there.

But it didn’t because the Americans wanted the unconditional surrender, so the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and civilians were vaporized.

And yet, and this is the kicker, the Japanese still didn’t surrender. What actually triggered the surrender was a telegram from the flustered Americans saying that Hirohito “would have work to do”, heavily implying that Hirohito would keep is head and position as emperor. The Japanese took that as the signal for the one condition they wanted, and surrendered.

So the Japanese got their conditional surrender after all. Ergo, the bombs were not necessary. It was a monstrous war crime that most Americans defend to this day by pretending the only other choice was a costly ground invasion.

I recently listened to Malcolm Gladwell’s audiobook The Bomber Mafia. It’s about American strategists in World War II coming to terms with the reality that their bombers were way way less accurate than they had expected. Your post, and questions about ethics in war, reminded me of it because I recall Gladwell discussing Carl Norden, the developer of the Norden bombsight. He said that Norden was a deeply religious person, and he felt like developing the bombsight was a thoroughly moral act, because it would allow wars to be shortened when people used it to cripple their enemies’ war-fighting ability and force them to the negotiating table sooner. Although I realize aiming conventional bombs more accurately is a long way from using an atomic bomb, it seems like a maybe related question.

https://www.goodreads.com/tr/book/show/56668328-the-bomber-mafia

Oh, and another book I’m reminded of is Daniel Ellsberg’s The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner. A point I found particularly striking was that when a number of scientists refused to continue work on nuclear weapons as they moved from the early fission bombs to higher-yield fusion bombs, they argued that fusion bombs were always wrong to use. They produced such massive explosions that they were just by definition a weapon aimed at civilians and designed to terrorize rather than simply cripple an enemy. I don’t know enough about weapon yields and bigger and smaller bombs, but it did seem like a really good point to me.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/36982630-the-doomsday-machine

I recommend for all to read “The Making of the Atomic Bomb”, & “Dark Sun”, both by Richard Rhodes. Some of these issues come up in those books.

Would there have been a US A-bomb without Oppenheimer? Yes. Would there have been a Soviet A-bomb without espionage? Yes. They also had some brilliant scientists, like Georgy Flyorov, Igor Kurchatov, Abram Ioffe, and others. The German attempt at an atomic reactor was just a little short in size of sustaining criticality. There was one Japanese scientist, who also worked on making an A-bomb, but, had few resources devoted to that plan.

“Is it more ethical to end a war with a single event that might overall save lives on both sides, but will kill tens of thousands (or more) of civilians?” Well, one Japanese General felt they could sacrifice 20,000,000 people, in an all out war, that would ensure Japanese victory. This was after the dropping of the 2 bombs.

“Once the genie is out of the bottle, what can we actually do about it?” Bohr wanted Soviet involvement early on, before the bomb was completed, in joint world control of nuclear weapons, but Churchill flat out refused that idea.

Fairly late to this, but I just wanted to say that the movie did a fairly good job on the ethics of the Manhattan Project and nuclear weapons in general. It doesn’t portray them as necessary, it merely tees up the debate. Given that the subject matter was the ethics of nukes and their ability to destroy the whole world, I was pleasantly surprised that the movie did try to address other ethical issues. The characters are hardly lionized and make significant errors, such as Oppenheimer stating that the test would not hurt anyone so long as there wasn’t a big wind storm (there was). Nolan didn’t have to put that line in there, but did so to nod at the other effects of the bomb on local and indigenous people. Similarly, the movie had many references to toxic sexism in the field of nuclear weapons, to the point I wondered if they read the actual academic literature on the subject.

My point is, this movie is worth watching if you want to see someone tackle and even critique the way our society thinks about nuclear weapons. There are certainly things they missed, but their focus was the existential threat of nukes and they stayed focus on that important topic. Hours and hours of movies and books upon books ought to cover other dimensions as well. But given the threat of nuclear weapons use is increasing since its nadir in the 90s, it’s a topic we ought to be discussing in it’s own right.

I’m also late to this discussion, without having seen the movie yet.

I have come to regard the development and use of the bomb as inevitable. Whether or not it was justifiable under the circumstances, I think if it hadn’t been used then, someone would have eventually used a similar one. The world needed an example to understand what it was capable of. The same has been true of chemical weapons. We have succeeded in substantially but not completely eradicating them, but only after seeing what they do. There will always be someone willing to push boundaries in the use and development of highly destructive weapons. Military policy has to take that into account. Whether that means being drawn into an arms race is the correct answer I’m not sure, but whatever we do we must accept certain realities.

Regarding the ethics of war, I’m reminded of an episode of The West Wing in which the president, his chief of staff, and the chairman of the joint chiefs discuss whether they could be tried for war crimes for having previously ordered the murder of a known terrorist (in an earlier episode that presents some fascinating ethical dilemmas). At some point, the military guy says “all wars are crimes”. I think I believe that, while also believing the possibly contradictory position that there is still such a thing as a war in which one side is fighting for a just cause. Sometimes the just cause is hard to identify; sometimes it’s more obvious. Having been a missionary in Ukraine, I have many friends whose lives have been upended by the war there, and I’m obviously deeply sympathetic to their cause. I can’t help but believe they are justified in fighting off the invasion that they did not choose. But, I’m still not sure anyone ever comes out of a war completely innocent.

In response to your question about how the cold war affected me, I would give 2 answers. First, it made me exceedingly curious about the Russian people and their language, such that I jumped at the opportunity to study Russian in school when it was offered, which likely was a factor in my serving a mission in Ukraine during the dying days of the USSR. The second way is one that I didn’t appreciate until recently. I grew up less than 20 miles from a nuclear weapons factory. Apparently we lived in what is now referred to as the “downwinders zone”, and there is now evidence of elevated rates of assorted health problems among those who live there. Where we lived isn’t considered the most affected area, but in my immediate family there seems to be an unusually high rate of infertility, birth defects and cancer, and we’re now wondering whether where we lived was a factor.