I’ve been reading Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. It’s about the problems with systems that appear to be peaceful or stable. Fragile systems appear placid, but when an unforeseen event happens, it can be catastrophic, whereas robust systems appear more stressful and unstable but are actually more resilient when something unpredictable happens. Since we can’t predict things that are unpredictable, such as the impact the internet on how we gather information, we should instead stay attuned to evidence that the system is fragile or essentially too quiet.

The comparison is made between two siblings: one in a seemingly stable corporate job, the other a taxi driver. The sibling in the corporate job seems to have a low-risk existence, steady income, and predictable paychecks. The sibling who drives a taxi seems to be always dealing with unpredictable problems: lower or higher fares, risks of dealing with the public, seasonal ups and downs, car maintenance, traffic. And yet the taxi driver also has the ability to adjust in real time to market factors due to more direct engagement with her customers. If she’s not getting fares at the airport, she can try the port. The sister working in a corporate job, by contrast, is insulated from these market fluctuations behind her desk and steady paycheck. If the market goes up or down, her paycheck stays the same. And while it would seem that she has more security, what she also has is vulnerability to a catastrophic event such as a layoff.

We can’t avoid catastrophic events. We can only increase our ability to weather them by reducing their impacts should they happen. And the starting point is determining that a system or organization is fragile. Peaceful systems that appear to be free of conflict are the most fragile there are. Human beings should have conflicting viewpoints; ideological clashes are normal. Lack of disagreement is most often a sign of repression or disengagement. The most tightly controlled, predictable environments are the most fragile. I don’t know about you, but the Gospel Doctrine classes I’ve been attending are pretty doggone predictable, and thanks to correlation–very controlled.

We can’t avoid catastrophic events. We can only increase our ability to weather them by reducing their impacts should they happen. And the starting point is determining that a system or organization is fragile. Peaceful systems that appear to be free of conflict are the most fragile there are. Human beings should have conflicting viewpoints; ideological clashes are normal. Lack of disagreement is most often a sign of repression or disengagement. The most tightly controlled, predictable environments are the most fragile. I don’t know about you, but the Gospel Doctrine classes I’ve been attending are pretty doggone predictable, and thanks to correlation–very controlled.

Since the inception of the bloggernacle I’ve heard (and experienced firsthand) that teachers who use non-correlated materials or ask too many off-script questions are often removed from teaching assignments. We prefer to ask the same questions and get the same answers, over and over, every 4 years, lather, rinse, repeat. It’s not always like that; some wards are better than others at bringing questions to the surface, but the correlated curriculum is particularly designed to ask the questions it wants answered, not the questions people might ask in a more direct engagement with the text. And when we suppress that engagement, we are creating fragility.

What makes the species prosper isn’t peace, but freedom.

Without that freedom to think and discuss, people disengage and don’t build the skills necessary to handle challenges in the future. In his essay, Sam explained:

Assertion is easy, and allows us to be lazy in constructing our beliefs. When we have to defend our assertions, we see the weaknesses, the places we need to study more, the places we need to look for further revelation.

Testimonies aren’t built on assertions, but on subjective experiences with which we struggle to derive meaning. As Steven Peck put it in his book Science the Key to Theology:

Anyone who knows me knows I change my mind almost constantly, and by the time this book comes out I will have a new set of questions that I am exploring and playing with. This is not to say I have no core of beliefs. I do, but I must admit that they are not rationally derived. They come from experiences that have come to me subjectively placed in my heart, and it is these that I hold onto dearly.

Now that’s an antifragile testimony! He continues:

Failure often offers the most insightful commentary about the system because it exposes the misunderstandings and mistakes in our theories.

In a system such as church classes in which the questions and answers are pre-scripted by correlation, those misunderstandings and mistakes–those system failures–are hidden under a veneer of peacefulness and passive engagement. Like a Gregorian chant, the questions are put forth, and the predictable answers are chanted back.

When a system is too peaceful, small problems accumulate and are more catastrophic than they might be if they were openly discussed when they are small. The system would then self-correct and deal with that new information. For example, much has been made of the church’s need to address gaps in members’ knowledge of history due to simplified narratives in the curriculum that are inaccurate. If we were having more free-form discussions in our classes, individuals would be better equipped to handle new information because they would be used to challenging ideas and concepts. In the bloggernacle, this is often referred to as inoculation. One dictum could be “lack of inoculation leads to disaffection.”

Small forest fires periodically cleanse the system of the most flammable material, so this does not have time to accumulate. Systematically preventing forest fires from taking place “to be safe” makes the big one much worse. For similar reasons, stability is not good for the economy: firms become very weak during long periods of steady prosperity devoid of setbacks, and hidden vulnerabilities accumulate silently under the surface–so delaying crises is not a good idea.

One thing that has always bothered me about the CES Letter that has made the rounds (aside from its resemblance to a faithful dog that leaves hideous carnage on your doorstep and expects to be recognized as a “good hunter”) is that it simply lists a litany of flaws with various church teachings, but it is addressed to a CES Director as if it is up to the Church Education System to answer these questions. That’s a byproduct of a fragile system, one that appears to be peaceful only because everyone goes quietly along, keeping things “safe,” while not having the smaller discussions as we go. People at the bottom expecting top down answers are evidence of a fragile system, one in which little is expected of them, and disagreement is not open or welcome. Instead of small forest fires, the CES letter represents an accumulation of flammable material, one that has consumed many trees (both literally and figuratively). A system that is too peaceful with too little disagreement breeds literalism and lack of thinking skills; we assert (which is easy) rather than grapple with (which is challenging) our faith. We go along thinking all is well in Zion, pacified by the stability.

One thing that has always bothered me about the CES Letter that has made the rounds (aside from its resemblance to a faithful dog that leaves hideous carnage on your doorstep and expects to be recognized as a “good hunter”) is that it simply lists a litany of flaws with various church teachings, but it is addressed to a CES Director as if it is up to the Church Education System to answer these questions. That’s a byproduct of a fragile system, one that appears to be peaceful only because everyone goes quietly along, keeping things “safe,” while not having the smaller discussions as we go. People at the bottom expecting top down answers are evidence of a fragile system, one in which little is expected of them, and disagreement is not open or welcome. Instead of small forest fires, the CES letter represents an accumulation of flammable material, one that has consumed many trees (both literally and figuratively). A system that is too peaceful with too little disagreement breeds literalism and lack of thinking skills; we assert (which is easy) rather than grapple with (which is challenging) our faith. We go along thinking all is well in Zion, pacified by the stability.

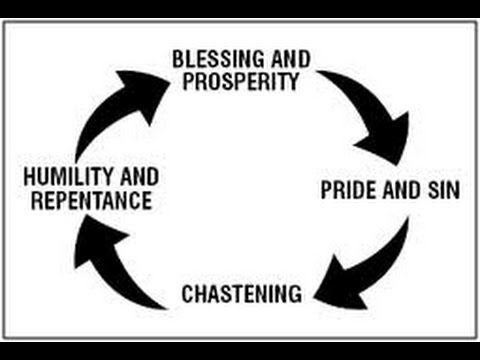

Perhaps the pride cycle described in the Book of Mormon works like the forest analogy. Often, we interpret it as a cautionary tale about the downfall that comes when a society achieves wealth. In light of antifragility, the pride cycle describes what happens to a system that appears too peaceful. Eventually, an unforeseen event causes it to crash. Rather than blaming the catastrophic event or the “pride” of wealth, antifragility would teach us to be wary of too much peace, too little disagreement, too much correlation, and not enough small disputes.

When you avoid the little skirmishes and congratulate yourself on the lack of conflict, the eventual war can be devastating.

- Is the lack of open discussion and multiple viewpoints in the church a problem? If so, what do we do about it?

- Is it important to make our system antifragile or is it OK if it’s fragile (and therefore will lose large parts of the membership)?

- Do you think the church is more or less fragile than other churches?

Discuss.

*This is a modified reprint from a post I did on BCC.

You make some very good points in the idea that the people of the Church have settled into a predictable-is-preferred state. I feel that that is largely a cultural bleed-thru from the world culture that the local population is exposed to every day rather than a by-product of what the Church does per se. People tend to bring with them to church the very cultures (attitudes, expectations) they experience outside of church. So, for me, the fragility mindset is more a byproduct of the fragility culture promoted in the current westernized cultures…and people are taking that to church. To me, it’s just an example of how cunningly the world can infiltrate a society…and then its churches.

Maybe that’s why I like to encourage “out-of-the-rut” discussions anywhere I go and still maintain contact to the core doctrine being presented. It kinda shakes up cultural norms while keeping people connected to what truly matters in discussion: drawing nearer to God.

I don’t think we’ve seen all of the carnage the internet triggered paradigm shift has caused to the church yet. The church is loosing it’s youth (72% ? as I recall) while retaining only a fraction of it’s new converts (25% ? as I recall). How long can this continue before negative growth becomes obvious? In this sense the church has proved to be very fragile. More fragile than other churches? I think that remains to be seen.

The church’s current product is clearly being rejected by the marketplace, since it is unlikely that the market will change to embrace the product positive growth will not reoccur until the product is redesigned to address the market.

As much as I would like to do something about it, I feel pretty powerless to do so. Just like forest management, the people in charge have to allow the small fires to happen to prevent the larger catastrophic fires. If the leaders won’t allow the small fires, the larger ones are going to be worse. As a lay member, I can advocate but the leaders have to show a willingness to listen, something they have shown little interest in. They like the fragile system because they think it isn’t fragile but the lack of fires shows “good management.”

“Is the lack of open discussion and multiple viewpoints in the church a problem? If so, what do we do about it?”

I’d say, Yes.

We could stop prioritizing unanimity and feeling the spirit over learning. Stop trying to make GD an extension of Sacrament meeting. Use lesson time to make delicious and interesting food for thought, instead of everyone unwrapping and eating their survival bar.

(I use Gregorian chant as white noise to fall asleep to, so your comparison is spot on!)

The lack of open discussion to me makes church boring as, well, hell. What do we do about it? Do you mean other than zoning out and read stuff on my phone? It seems if you do much about it you get punished in most wards.

I like Patrick Mason’s take on that we have put too many things in the truth cart until it is overloaded and it crashes. I think there is a balance and not much agreement on what the balance is. I am fairly sure if you took Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, or most of the early latter day prophets into our church today, they would have a fit. It isn’t the same church.

And if I think it should be more fragile or anti-fragile, not sure if it matters. But I do think how it is now is affecting the church members (and ex-members).

Do you think the church is more or less fragile than other churches? I think it depends. I am reading a bit about Jehovah Witnesses and it seems fairly close. If I look at Buddhism or the Bahia faith, we look rather rigid. Wasn’t Romney mocked a bit for being “rigid”? 🙂

“Is the lack of open discussion and multiple viewpoints in the church a problem?” If you’re trying to control an international church, I can understand how you might prefer more unified viewpoints. MH is right that discouraging dissent makes you look more successful from the outside. I’d prefer more open discussion, but I’m not sold that the Sunday bloc is always a good place for debate. If you are having to defend your religious beliefs every day, the last thing you want to do is walk into a room and have to defend your *version* of your beliefs with your co-religionists. I think people are justified in wanting a space with an implicit assumption that everyone shares certain beliefs and works to support each other in those beliefs.

The difficulty is what people are wanting from church. Everyone has a different preferred mix of intellectual stimulation/self-improvement, social cohesion, and outward service. Open discussion just isn’t a priority for a lot of people, including many leaders. As one GA argued recently, he’s got more pressing things to do than learn about church history.

“Do you think the church is more or less fragile than other churches?” We should be *less* fragile than other churches because of our belief in continuing revelation, but that doesn’t seem to be reality.

“Is the lack of open discussion and multiple viewpoints in the church a problem? If so, what do we do about it?” I think it’s both a problem and in some cases, it’s not. There used to be a lot of rampant speculation in the 70s and 80s that seems to be less prevalent now, but the pendulum has probably swung too far the other way. IMO, the real problem is that both speculation and correlation are giving members top-down answers rather than asking thought-provoking and life-changing questions that we can individually use to challenge our thinking as human beings. That’s what creates morally strong people, not uniformity and rules.

“Is it important to make our system antifragile or is it OK if it’s fragile (and therefore will lose large parts of the membership)?” Personally, I don’t see fragile as a positive.

“Do you think the church is more or less fragile than other churches?” This is a tricky one. Some aspects of our church (like MaryAnn says, revelation – particularly personal revelation – are anti-fragile. Local wards having oversight for church discipline and callings are elements of anti-fragility. Whenever the over-arching corporation gets involved or is too pushy about its agenda, though, that will always create anti-fragility. And when the local ward doesn’t do what makes sense locally because of “corporate” level rules, that’s going to lead to anti-fragility.

The best way to make Sunday school more interesting is from members of the class rather than the teacher. The teacher has a responsibility to represent the church as best as they can. Students should come being prepared to engage in meaningful ways, and find appropriate ways to do that.

It seems that there is a pendulum to all of this. The chaotic organization will tend toward stability, while the peaceful will tend to become more fragile. Would this not potentially be a cycle?

Correlation, which has among its purposes both the goal to present a consistent message and to simplify translation of church materials, has made the church more spread out but perhaps more fragile. The correlated manuals enable anyone to step up and teach modest Gospel Doctrine lesson, but the insistence that we stick to the manual can prevent the lesson from being much better than that. Being a world wide church may make the church more anti-fragile[1], but forcing the correlated messages to be the only thing taught makes the church more fragile.

[1] I like the term anti-fragile, but it reminds me of the saying: “Never use a big word when a diminutive alternative would suffice.”

I do not find the church to be fragile at all. The average sacrament meeting attendance in my ward in southern Idaho is around 200 people. As near as I can tell, everyone in that room has had some grand revelation that the church is true. I don’t even know what in the hell that means, but they tell me they know it every month. How can an organization be fragile if everyone in it knows it is true?

I try my best to start a fire every week, but it is quickly extinguished by a group of about 5 people who take turns bearing testimony to the contrary of every comment I make. If I had one ally in the room I might feel a little less bullied. I have been dreading studying the D&C in GD and all of my fears have been realized. The ignorance of 60 and 70 year old members to our church history is astounding. If open discussion is the key to making the church less fragile long term, we are doomed. Maybe in wards outside Utah and Idaho it is different, but it is not happening here. People go to church to hear warm fuzzy messages about how someone saw a dead person in the temple or somebody had a tumor disappear after a priesthood blessing.

I went to a priesthood leadership meeting just last week and the discussion was on building testimonies in the youth. I brought up that we maybe should employ some of Elder Ballard’s suggestions in the article By Study and By Faith and maybe address some troubling history. I was told by the councilor in the Stake presidency that I was wrong, and that those tactics would not build faith. I also petitioned in a bishopric training to teach the essays as fifth Sunday lessons and was told they are not to be taught.

If a future fire is coming, hopefully our seers see it in time and give us better instructions on how to avoid it. In the mean time if we lose a tree here or a tree there it really is no big deal. Unless it is your kid that is.

Ruth says, rightly IMHO, We could stop prioritizing unanimity and feeling the spirit over learning.

I’d add that the sort of unanimity we often get in GD is not the same as “feeling the Spirit.” Manufactured mass-media emotion, like crying at the end of a romantic movie, isn’t really the same thing. I find that I feel the Spirit when I can learn some new truth, since it’s the Spirit’s job to testify of it. You’d think the Spirit would get tired of testifying to the same old correlated lessons over and over again, and just stay home since S/He clearly isn’t needed anymore. It’s all in the manual.

This is a really interesting perspective I’ve never quite thought of before, but I totally agree. I think this is a principle that is true for a lot of different things, including my own craft of software development. Code that does not prepare for all the crazy stuff users will do to it WILL crash. Enterprise software development forgets about change and then creates bugs when a feature is added because it’s inflexible.

I agree that there is a serious lack of varying viewpoints in the church and it is a problem. Creating a one-size-fits-all environment is about as dumb as writing code that does not properly accommodate for errors. People cannot be programmed. There will always be black sheep. Do not alienate them.

I can’t really speak for all churches, but I would say from my outside observation that our church is more fragile than most nondenominational churches. Most of them are more accepting of alternative viewpoints and making mistakes, adopting an attitude of “come as you are” rather than cramming robotic responsibilities down their throats to try to ‘fix’ the members.

Fragility is bad. Very very bad. Life is full of problems and we need to be equipped to deal with them.

This is literally the only post of yours (that I’ve read) that I agree wholeheartedly with.

Love Taleb and have been advocating to my social circles the concepts you have elucidated in this article.

Good job.

Now, if you could only get the rest of your thinking screwed on straight…. 😉