Sometimes when I hear other people talk about what they get from their church experience, I wonder if we attend the same church. I’m sure they feel likewise. The things that matter to some people aren’t important to me, and the things I care about aren’t important to them. Some people complain about things that don’t bother me, and sometimes it bothers me that people don’t feel as strongly as I do about what does bother me. That’s the nature of being a part of any organization.

Sometimes when I hear other people talk about what they get from their church experience, I wonder if we attend the same church. I’m sure they feel likewise. The things that matter to some people aren’t important to me, and the things I care about aren’t important to them. Some people complain about things that don’t bother me, and sometimes it bothers me that people don’t feel as strongly as I do about what does bother me. That’s the nature of being a part of any organization.

Andrew S has previously posted on Seeing Mormon Faith Transitions as Social Movements, a post that describes some of the different sub-cultures within Mormonism. The post was helpful in understanding some of the ways we talk past each other as well as describing what people hope to obtain from their church-going experience; news flash: we don’t all care about the same things to the same degree. The three different aspects of church he described were:

- Physical Infrastructure–people who use Mormonism as a vehicle to serve others and grow.

- Cultivation of Relationship–people who see Mormonism as their family and tribe.

- Intellectual Infrastructure–people who want to grapple with theological questions.

Inherent in these three groups he described are common misunderstandings. For example, a person who sees church as a vehicle for service may not understand why historically inaccurate information in our church manuals matters to someone else. While his explanation was helpful, I have continued to be intrigued by the culture clashes that occur within the membership of the church, and sometimes between members and leaders’ ideas of what Zion entails.

Inherent in these three groups he described are common misunderstandings. For example, a person who sees church as a vehicle for service may not understand why historically inaccurate information in our church manuals matters to someone else. While his explanation was helpful, I have continued to be intrigued by the culture clashes that occur within the membership of the church, and sometimes between members and leaders’ ideas of what Zion entails.

David Brooks from the New York Times wrote an interesting article over the weekend that describes the perspectives coming from different places within one’s political party. These descriptions work well to describe the differences in perspectives depending on where one fits in the “tent” of Mormonism, whether the “pillar” (near the interior support structure) or “post” (near the edges, fences or outside of the tent).

In any organization there are some people who serve at the core. These insiders are in the rooms when the decisions are made. . .

There there are outsiders. They throw missiles from beyond the walls. They are untouched by internal loyalties and try to take over from without. . .

But there’s also a third position in any organization: those who are at the edge of the inside. These people are within the organization, but they’re not subsumed by the group think. They work at the boundaries, bridges and entranceways.

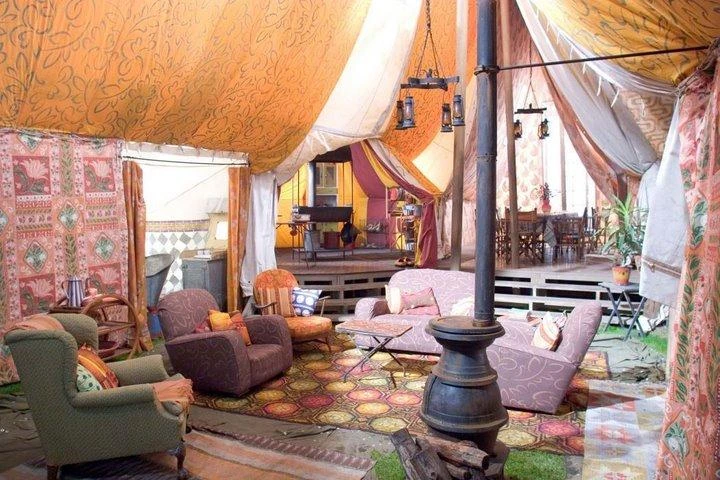

We like to talk about “Big Tent” Mormonism a lot in the bloggernacle, and it’s been referenced in General Conference in recent years as well, the idea that we want the tent of the church to be inviting of many diverse people, not just those who look and think like we do. We want growth and retention. We want to invite all to come unto Christ. The analogy of a tent is comfortable because Isaiah talks about strengthening the “stakes” in Zion. But one’s perspective alters radically based on where one stands in the tent, to the point that it can feel like an entirely different culture. Toward the center, you may not even realize you are in a tent at all. Toward the edges, the structure is much more apparent. You can see what lies outside as well as the inside. The expression “from pillar to post”[1] refers to a person suddenly racing from one place to another, caught between places, feeling run ragged, a feeling some on the fringes have found difficult. As Brooks describes it:

We like to talk about “Big Tent” Mormonism a lot in the bloggernacle, and it’s been referenced in General Conference in recent years as well, the idea that we want the tent of the church to be inviting of many diverse people, not just those who look and think like we do. We want growth and retention. We want to invite all to come unto Christ. The analogy of a tent is comfortable because Isaiah talks about strengthening the “stakes” in Zion. But one’s perspective alters radically based on where one stands in the tent, to the point that it can feel like an entirely different culture. Toward the center, you may not even realize you are in a tent at all. Toward the edges, the structure is much more apparent. You can see what lies outside as well as the inside. The expression “from pillar to post”[1] refers to a person suddenly racing from one place to another, caught between places, feeling run ragged, a feeling some on the fringes have found difficult. As Brooks describes it:

The person on the edge of inside is involved in constant change. The true insiders are so deep inside they often get confused by trivia and locked into the status quo. The outsider is throwing bombs and dreaming of far-off transformational revolution. But the person at the doorway is seeing constant comings and goings . . . . She is involved in a process of perpetual transformation, not a belonging system. She is more interested in being a searcher than a settler.

Insiders and outsiders are threatened by those on the other side of the barrier. But a person on the edge of inside neither idolizes the Us nor demonizes the Them. Such a person sees different groups as partners in a reality that is paradoxical, complementary, and unfolding.

There are downsides . . . you may be respected and befriended, but you are not loved as completely as the people at the core . . . you enjoy neither the purity of the outsider nor that of the true believer.

But the person on the edge of inside can see reality clearly. The insiders and the outsiders tend to think in dualistic ways: us versus them: this or that. . . .

When people are afraid or defensive, they have no tolerance for the person at the edge of inside. They want purity, rigid loyalty and lock step unity.

This is why it can be uncomfortable to be near the edge of the tent, and yet, once you’ve been on the edge of the tent, you really can’t quit seeing it that way. You begin to know the outside as well as the inside, and you respect them both. You aren’t afraid of what’s outside (because it’s not unknown) even if you choose to remain inside.

This is why it can be uncomfortable to be near the edge of the tent, and yet, once you’ve been on the edge of the tent, you really can’t quit seeing it that way. You begin to know the outside as well as the inside, and you respect them both. You aren’t afraid of what’s outside (because it’s not unknown) even if you choose to remain inside.

One other aspect of the edge of inside that Brooks describes is that person’s role in relation to the rules:

A person on the edge of the inside knows how to take advantage of the standards and practices of an organization but not to be imprisoned by them. Rohr writes, “You have learned the rules well enough to know how to ‘break the rules properly,’ which is not really to break them at all, but to find their true purpose: ‘not to abolish the law but to complete it.”

David Holland wrote an interesting OP in the Deseret News over the weekend about why Trump’s pitch to Utahns fell flat. He said that Trump painted Mormons with the same brush as he paints Evangelicals, and in so doing misunderstood the complexity and paradox of Mormonism.

Among the elements of the Latter-day Saint tradition that I hold most dear is its tireless determination to embrace principles that others find incompatible. We loudly insist on the sacred coexistence of grace and work, body and spirit, law and mercy, personal inspiration and prophetic authority. These and other paradoxes have brought claims of heresy, hypocrisy and inconsistency from critics; they also provoke repeated bouts of soul-searching among ourselves that lead to fruitful introspection. It is not easy to live at the convergence of competing truths. It requires constant effort. But whatever else we may be, we have never been known to shirk from working hard for the things we value.

One of those paradoxes is that between community obligation and personal freedom and accountability. Being on the edge of inside, near the post rather than the pillar, the risk is that we will turn our back on community obligation toward our fellow Mormons becoming mere cultural anthropologists, in order to preserve our personal freedom to believe as our conscience dictates and to create boundaries to keep purists and busybodies off our lawn.

One of those paradoxes is that between community obligation and personal freedom and accountability. Being on the edge of inside, near the post rather than the pillar, the risk is that we will turn our back on community obligation toward our fellow Mormons becoming mere cultural anthropologists, in order to preserve our personal freedom to believe as our conscience dictates and to create boundaries to keep purists and busybodies off our lawn.

It also lies at the root of Latter-day Saint teachings regarding the divinity of personal agency and the sacredness of communal obligations. Mormon communities are responsible for their individuals, and Mormon individuals are responsible for their own choices. We believe that cohesive communities are essential and free individuals are of great worth.

I suspect that Holland is both right and wrong. These paradoxes do exist at the heart of Mormonism, but his OP is also an appeal to the best within our ranks. He overlooks, perhaps deliberately, the willingness of many members to sacrifice personal accountability in the name of ring-kissing fealty and to allow communal obligations and respect for authority to erase boundaries. As Brooks points out, the sweet spot is in the balance of both personal accountability and communal obligation.

What do you think?

- Do you experience cultural clashes between those at the pillar or center of the church tent and those at the edge of the inside or post of the tent? Where do you find yourself? Why?

- How do we balance the communal obligations with the personal freedoms and accountability?

- Are these paradoxical tensions characteristic of Mormonism in a way they are not of other religious groups?

- Are Mormons at the edge of the tent of Christianity in a way that Evangelicals are not? Does this make us more or less empathetic to those on the outside?

Discuss.

[1] From the Aztec Camera song “Pillar to Post”

Once I was happy in happy extremes

These bitter tokens are worthless to me

So you appear and say how I’ve grown

Fill me up with faces I’ve known

In this light, they’re far from divine

I save them up and spend them when I have time

The salted taste of all your tears and woes

Sent me in haste, my melancholy rose

Those tasteless lips were closed

You watched me come, you see me go

Once I was happy in happy extremes

Packing my bags for the path of the free

From pillar to post, I am driven, it seems

These bitter tokens are worthless to me

Just like June, the curtains are closed

The ghost of shame, he sits here and sighs

I love the flames like I’ve loved the cold

I’ll learn to love the life of the ‘Could I, Could I, Could I’

So I don’t cross my fingers any more

You look for rags and found them at your door

How could you ask for more

Than everything you’ve heard before?

Mom and Dad sit in the center of the tent, and the children are on the edge of the inside. Yes, the children do have a different perspective, and they see sometimes more of the neighbor’s goings-on than Mom and Dad. But I suppose Mom and Dad have seen it before.

Words are inadequate to explain spirituality it must be experienced to be understood. Religion is the mortal-ization of spirituality or the attempt to explain spirituality using words, symbols and rituals. Since religion is NOT spirituality we can easily conclude that any church even THE church will necessarily be different in mortality than it will be in the afterlife. From this view we can see that religion is a transition rather than a destination.

Those at the center think they have arrived at a destination. Outsiders moving in are in transition. Insiders moving out are in transition. Transition is growth be it moving inward or outward. Lack of transition is stagnation. The church might be thought of as the narrow part of an hour glass.

I like the pillar/post metaphor because it infers that BOTH pilar and post are essential dimensions of the structure, and must be held in tension. The fact that we disagree so strenuously from pillar to post is a measure of the structure’s strength, not it’s weakness, unless the chords are snapped.

Regarding paradox, I think that from the perspective of the pillar, there is no paradox, and as you get closer to the post, the paradoxes become apparent. At the pillar, there is no paradox between personal revelation and authority because they never conflict. There is no paradox between justice and mercy because every sin has to be accounted for, either by the sinner, or by an extra drop of blood Jesus has to shed. There is no paradox between grace and works because grace is just a reward for righteous works. There is no paradox between flesh and spirit because any sinful instincts you might feel don’t come from your natural flesh, but from Satan.

All this starts to dissolve the further we get from the pillar.

Nate: Exactly! So when David Holland describes the paradoxes of lived Mormonism, my immediate response is that I don’t think that’s a universally true description at all. There are many many Mormons who don’t sit around pondering paradoxes. His experience is colored by where he lives, in an area renown for liberal thinking church members and individuals closer to the post than the pillar.

The other thought I had about this cultural distinction is that it reminded me of TCKs (Third Culture Kids), kids raised between cultures such as the children of expats, who never truly belong to their culture in the unquestioning way that those do who haven’t experienced other cultures. TCKs see the assumptions of both the Us and the Them and can observe them from a distance in a way that you can’t if you are either an Us or a Them. But TCKs never really belong to their surrounding or native culture either. They may choose to be a part of one or the other, but it’s deliberate. They generally are part of a third culture, one that doesn’t really exist as a stand-alone but is a group of others who are between cultures, observers more than belongers.

There are a few conflicting ways to take the tent metaphor. If the tent is church doctrine/testimony, then a lot of people would argue that moving towards the center is preferable to spending time on the periphery. Moving toward the center would be seen as increasing in devotion. Staying on the periphery looking longingly at the outside is equivalent to Lot’s wife, a lack of faith.

If you take the tent as church institution, then moving towards the center becomes a matter of loyalty. Being on the periphery and pointing out flaws (while similarly pointing out advantages in other tents) is criticism of anointed leaders – again, periphery is bad.

Then there is seeing the tent as a community of Saints. We would consider the welfare of those on the inside and those on the periphery as equally important – urging those on the center to reach out in fellowship to those on the periphery, and those on the periphery to reach out to those in the center. Both those in the center *and* those in the periphery would also be expected to reach out to those outside the tent with compassion and respect for the benefit of a larger community.

Right now, everything (religious and political) seems to be ideological – us versus them. There is no overarching community. I agree that Holland is idealistic – ultimately politically conservative churchmembers *will* vote for Trump because living with him for 4 years will be worth the chance of getting conservative supreme court justices. Mormons value loyalty to the cause, even if the leader is flawed.

Your post reminds me of the oft-cited Winston Churchill post wherein he characterized himself not as a pillar of the Church but rather as a buttress–supporting the structure from the outside.

For some of us, we know where the tent is located and will occasionally travel to visit family members and loved ones who reside therein; but we prefer to sleep under the stars (I realize the metaphor fails when one considers inclement weather).

I particularly like this point, Hawkgrrrl: “Toward the center, you may not even realize you are in a tent at all.”

That makes a lot of sense to me. If you’re all the way in and you’re surrounded by others in a similar situation, it’s difficult to even see the edges of the tent, or know that they’re there. There’s just what’s around you and everything else.

I really like this post, but I struggle with the tent analogy. First, I don’t know where I’d fall. I think most people would consider me well within the tent, but I think I’m capable of seeing and appreciating things outside it. Second, it makes both those on the outside and those on the inside seem… static. As though they’re smugly content and complete. I really don’t think that’s the case, at least for the people I know who I’d consider firmly in the center of the tent. I like David Holland’s description of us struggling with paradox much better (of course I would — the piece makes us sound really good) and that’s what I see with a lot of my friends.

Martin: I think these are good points. The problem is that to put it another way, the tent analogy makes those in the innermost parts of the tent seem provincial, which is usually a pejorative. There probably are some who are, but there may be others who are not.

Perhaps (to stretch the analogy further) there are people who move with more ease throughout the tent. That’s probably not me. I am definitely more of a near the edge of the tent person. I have an aversion toward most affiliations and entanglements. Politically, I’m an independent, but I really just don’t like to be pinned down.

To put it in terms of the four-fold mission of the church, two of the four benefit from being nearer to the border of the tent: missionary work and poverty outreach. Two may be better done within the deeper recesses of the tent: perfecting the saints and redeeming the dead.

Interesting Hawk. Good perspective.

Well Hawk, I think all four missions of the church are best accomplished by movement throughout the tent by all members over time. The center must have the outliers come inward to keep fresh perspective and changing reality part of the pillar. Long time pillar-ites help keep stability, but cannot stay forever in the center or their perspective and reality check ends up coming to them second hand, which is never as good as experiencing both first hand. Everyone needs to stand at every place in order to fully understand the eternal truth that the whole is greater than the sum of its tent.

And I would add that all must leave the tent to climb that high mountain of the Lord. The tent is where we camp at night so-to-speak. But the mountain is where we ought to be, helping ALL to reach the summit. The fresh air is fabulous. The climb is exhilarating, yet taxing. The vistas open new horizons we can never “see” from the tent, whether pillar or post.

May we ever move about when within the tent for rest and nourishment……more, may we get out there and climb the Lord’s Mountain. And I say glory that. (This is a great “post” Hawgrrl,hahahahaha!)

There is an awful lot of modern, liberal (in the classical sense) ideology that has been built into this metaphor.

This ideology includes claims such as the following:

1) Interpretations that most “correspond to reality” – are most “objective” and “neutral” – are those which are the most morally praiseworthy. A higher truth is simply a better map of the terrain, so to speak.

2) Any deference to the decisions or perspectives of others is morally blameworthy.

3) That commitment and deference are obstacles to clear or right thinking.

4) That beliefs and perspectives are essentially private in nature, and as such only have derivative relevance to our social interactions.

The whole idea of weighing the pros and cons of being within, without or on the edge of the tent also presupposes these values.

Unfortunately, I don’t think the gospel teaches any of these values. Consider the alternative metaphors found within the BoM of the iron rod and the liahona. They do not care about objectivity or neutrality. They absolutely do teach that deference to the direction of others is a good thing. They teach that faith and commitment are the right way to think and that critical distance gained from the perspective of the tall and spacious building not only involves a private refusal to follow direction, but actively influencing other not to do so either (think of social influence that Laman and Lemuel’s endless questioning and doubting had upon the group).

Yes, the scriptures absolutely deny that people should be forcefully compelled to obey any religious tradition. But this is about as far as they are willing to go in their praise of “individual freedom”.

When we moderns, by contrast, start talking about the virtues of gaining an appreciation of diverse – and prima facie equal – alternatives, or the need for transparency in leadership, of having as much neutral/objective information as possible to make our informed choices for ourselves, or thinking that individual choice is the antithesis of deference to church leaders, etc. we not only go well beyond what the gospel teaches, but we actively contradict it.

The church does not preach individualistic freedom, but voluntary paternalism, and only one of these thinks that the edge of the tent is a good place for a church member to be.

Jeff G: I think you missed this paragraph in the OP which makes the same point you seem to be making: “One of those paradoxes is that between community obligation and personal freedom and accountability. Being on the edge of inside, near the post rather than the pillar, the risk is that we will turn our back on community obligation toward our fellow Mormons becoming mere cultural anthropologists, in order to preserve our personal freedom to believe as our conscience dictates and to create boundaries to keep purists and busybodies off our lawn.”

“Consider the alternative metaphors found within the BoM of the iron rod and the liahona. They do not care about objectivity or neutrality. They absolutely do teach that deference to the direction of others is a good thing.” No they don’t. These are both objects, not “others.” In these stories, the object gives direction, and the object theoretically is guided by God’s wisdom, not the wisdom of “others” or people. These are prophetic touchstones, not communal obligations.

“The church does not preach individualistic freedom…” Not true actually. The new site on religious freedom is preaching just that, the freedom for individuals to act according to their conscience, whether those actions are religious or not. Here’s the site: http://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/what-religious-freedom-means From that article: “More fundamentally, religious freedom — akin to “freedom of conscience” — is the human right to think and believe and also to express and act upon what one deeply believes according to the dictates of his or her moral conscience. This freedom applies to those who adhere to religious beliefs and those who do not.”

It has to be true that many Mormons don’t “sit around pondering paradoxes,” but I hope, even if it’s subconsciously, that we sense them.

I loved this post. Thank you.

Hawkgrrrl,

I realize that you weren’t totally buying into the ends to which the metaphor was originally put – in this sense, I wasn’t disagreeing with you since you were not defending the edge as such. But when you embrace a metaphor that was quite obviously designed with that end in mind, it will be very difficult to put it to any other purposes (it’s difficult to use guns for any purpose other than shooting things).

The problem, then, is that the metaphor has the edge of the tent already built into it as its final destination, regardless of whatever paragraphs you might include to the contrary. Yes, you acknowledge that one of the downsides of distancing ourselves from the community is that we will neglect the obligations that are native to it…. but this is phrased as one among many cons to be weighed against various other pros. This weighing is thus performed by a calculating individual who is making an informed and individualistic decision based in motives rather than in terms of obligations that are (or at least should be for any LDS) *already* regulating and evaluating such a choice. (This is the communitarian objection to liberalism in general.)

Put differently, you frame things as if communal obligations and standards of moral evaluation/obligation all lay downstream from individual motivations (pros and cons) and choices. Within this framework – and within this framework alone – the edge is quite obviously superior to being fully in or fully out of any community. Indeed, civil society was created and defended in the 17th century for the express purposes of fragmenting and mitigating full commitment to any such group since such a commitment (it was argued) was the cause of religious and civil wars.

But at no point does the church teach that membership is merely a personal choice in which different individuals seek to maximize different pros (your three aspects of church membership) over different cons based in their unique preferences. Rather, it is a *moral duty*, regardless of whatever the individual thinks on the issue – a duty which should be followed voluntarily.

No mortal can legitimately force you to stay in the church, but this does not mean that God will not judge us for this freely made decision or that non-members will ever be allowed into the celestial kingdom as non-members. Indeed, celestial, terrestrial and telestial just are the very non-neutral words that the church gives to “inside, edge and outside” the church, respectively.

You’re saying that only God can give us this direction. The problem is that your metaphor is aimed at replacing ALL external direction – even that of God – with an individualistic cost/benefit calculation regarding which type of direction or which aspects of membership are “right for us”. At best, the metaphor involves a temporary rejection of all prophets, both living and dead – since these teachings just are the tent within which we may or may not reside.

Yes, the church tells every person outside the church to do what they think is best. But to people within the church – as I assume most of your readers are – they say something far stronger and less-individualistic.

Hopefully this will be more to the point:

“In these stories, the object gives direction, and the object theoretically is guided by God’s wisdom, not the wisdom of “others” or people.”

That’s not right at all. You act as if each person got their own liahona, or that all people got to read, argue and/or vote about what the liahona said. This, however, is not what happened. Instead, everybody simply had to follow the “visionary” disillusions of Lehi and Lehi alone. Indeed, even when Nephi sought personal revelation on the matter, he was simply told to defer to Lehi’s direction rather than getting his own independent map that he could follow for himself.

And this just is the main point that I’m getting at: that mapping metaphors build a non-directional neutrality into themselves that is totally at odds with the directional and value-laden metaphors by which the scriptures describe our alignment with the Lord’s kingdom. This just is the difference between following an iron rod through the misty fog and seeking out a high vantage point from which to make our own, “more informed” choice regarding whether the iron rod “is right for me” and (in some cases) mock those who never seek this same higher vantage point from the tall building. Map metaphors make each individual the measure of goodness while directional metaphors give that authority to somebody else.

Your metaphor is a map without any direction built into it… and for this reason I think it’s unhealthy for church members.

I was going to say some comments similar to #8, Martin.

I don’t see my position as static. I don’t think others accurately see my position…I’ve been accused of many things and know others don’t understand me.

But I like metaphors, I like paradox.

I also see their limitations, but embrace their utility to discuss ideas.

I am not really sure I know what the tent represents for me in all honesty. I shouldn’t complicate it or read too much into it…the common analogy is the church and how it stretches out from Pillar to Posts. But what if the tent represents the gospel, not the church…the pillars and posts mean something different to me.

When I go to church on Sunday, I am not sure if I vew things as they are from the church (which I tend to dismiss) or the gospel (which I aspire to understand better)…all I know is I think I process it differently than others because of my experiences in life, but I hesitate to think I understand others in the pews any more than they understand my thoughts. Perhaps others think I’m near the pillar…when I never see myself that way. And then I get uncomfortable feelings thinking about labeling others vs me in any way, in or out or anyway.

Perhaps that is just as far as I can take a metaphor and it falls flat to me, and I take it for what it can help me think about, but leave it at the door as I head into the chapel and worship god and serve others.

I believe mormonism is complex enough to feed many metaphors and meaningful enough to lift all kinds of people…while all the different types of people try to figure it out…and while God laughs at our silly efforts as if we understood anything at all.

Many of you have expressed great ideas already. Thanks for sharing.

“You act as if each person got their own liahona, or that all people got to read, argue and/or vote about what the liahona said.” I didn’t say that. I’m just saying that the Liahona was the source, or the object used by the source, not Lehi. You could perhaps say that Lehi had to interpret what it said, but he wasn’t the source any more than the apostles are Jesus. I’m not acting like anything; you brought up the metaphor. I just don’t think it’s clearly saying that we have to follow “others,” just that we are supposed to follow a divine source. I’m not sure why you say a tent is a map metaphor. I think the tent is meant to signify the body of Christ, the collection of church members. You’re the one bringing up Lehi’s dream and the great and spacious building and whether it’s a pro-con decision making list; I was just trying to engage with your questions. My post is talking about the different perspectives depending on where you stand in the collective body of Christ (the tent).

“Your metaphor is a map without any direction built into it… and for this reason I think it’s unhealthy for church members.” Let’s say for argument sake that you are near the border of the tent simply because you don’t fit the mold. You are divorced or you are married to a non-member or you are gay or you just have an off-the-wall sense of humor. You don’t have to be there because you’ve made a conscious decision to be there. Some people just gravitate toward the edge of inside naturally. I don’t see where you’re getting a map out of a tent. I think you’re mixing metaphors.

By “map metaphor” I simply meant any kind of non-directional, lay-of-the-land or spatial metaphor that suggests

1) we can freely pick any direction that we want to go in since

2) there are no obligations that pull us in any particular direction.

I got the impression that your metaphor fulfilled both of these conditions. I apologize if I was wrong, and your explicit rejection of either (or both) of these points would be greatly appreciated.

Jeff G,

Revering feudalism just because it was here first doesn’t make feudalism ideal or right. The argument of individualism vs collectivism can’t even take place under feudalism but like it or not it is taking place (though in slow motion) today in LDS Mormonism.

Jeff G: when I wrote the post I was not thinking of movement within the tent, merely that people are at a certain place at a certain time and that based on that location, things look different to them. So I didn’t see the metaphor as describing movement at all.

I’ve been on record before as being a bit of a Haidt-ian. I like his elephant and rider metaphor. I don’t think we often know why we go where we go. We may think we do, but those are often after-the-fact explanations. I’m not claiming determinism either. I just think we are worked on by a variety of factors that we respond to in various ways, and we don’t really understand our true motives and reactions as well as we like to think we do.

To answer your question, I don’t think your two conditions fit the tent metaphor. I was also not talking about what Mormons “should” do, just why we often fail to understand one another. I don’t believe there is only one lived Mormonism. I think it varies greatly, and we sometimes forget that or simply aren’t aware of that.

Howard,

Nobody said anything about feudalism, so bug off.

Hawkgrrrl,

We both share an enormous respect and admiration for Haidt, so I absolutely applaud your effort at mutual understanding. I just worry that his pretended value-neutrality is itself a moral value about which he seems to have very little critical awareness. (His claim to have “removed himself from the political/ideological game” is the smoking gun, imo.) Like most people, he’s mostly right about other people, but not so much about his own actions.

Label it what you like Jeff this is a basic premise you often promote, that top down methods were here first and have stood the test of time but that is because they are used to restrain human growth and awakening.

I think I clearly find myself at the “edge of the outside.” I’m not sure how else to describe it, in Hawkian terms. (Other than to say that historical inaccuracies in Church materials drive me nuts.) But when we get right down to where the apostles pooped in the buckwheat, I’m not here because of a philosophical commitment to a particular point of view, although I have one. (Hawk’s mostly right, Jeff mostly misses the boat, being too infected by blackandwhiteism; but that’s irrelevant.) My philosophical viewpoint has developed from, and in parallel to, my study of the Gospel and may other things. It has matured and developed as I have matured and developed.

I’m in the tent, imperfect though the tent is and for as much as it could use a good airing out, because at one time in my life, I had what I regard as an undeniable, externally-driven, positive, unmistakable experience with God, and I have since had a number of other experiences confirming that. That’s all. Yes, it makes sense; yes, it’s coherent; yes, I think most criticisms of the Church are poorly thought out, poorly argued, and have been amply answered many times over in the last century and a half. But when boiled down to its essence, I have heard His voice, and know His words. Most of the time. The rest I work out with fear and trembling, as we all do. What I try not to do is throw the Baby Jesus out with the human bathwater.

Howard,

I think you’re in the wrong thread. If anything, my point here has been post-modern in a Macintyrean sense: http://epistemh.pbworks.com/f/4.+Macintyre.pdf

My point is that:

1) People at the inside, outside and edge of the tent will use different metaphors to try to “understand” each other – if only because they each a different evaluation of the merits of “mutual understanding”.

2) People like Haidt pretend that they have a special position “outside” of the three options – a view from nowhere – when they are actually legitimating some position or another that they seek to repress or disguise (whether it’s explicitly included within the metaphor or not is a different question).

There’s absolutely nothing “feudal” about this approach, nor does it devolve into top-down authoritarianism. I’m simply asking to critically engage the values that we inevitably build into any such metaphor as this.

Jeff,

There is an awful lot of top down ideology that has been built into your comments in this thread (as well as in other threads).

Howard and Iconoclast,

In a certain sense, of course you’re right. But probably not exactly in the sense that you mean it.

I am certainly arguing that people within the TBM tent will wield value-laden metaphors that have top-down directionality built into them: paths, rods, liahonas, degrees of glory, etc. All such metaphors have a strong “blackandwhiteism” to them.

Metaphors that do not build such a value-laden directionality into them (ones that are not “blackandwhitist”), obviously come from some place other than within the tent. The problem is that there is no getting outside of all tents. To stand outside *this* TBM tent just is to stand within another tent with its own value-laden directionality that defines it – even if it isn’t overtly top-down in nature.

I thus arrive at two separate conclusions:

(1) To the extent that any metaphor disguises the nature of its own tent (both the tent it presupposes and the one that it advocates – which aren’t always the same), we should be suspicious of it – and I think OP does exactly this.

(2) (This one’s more to your point.) The fact that this metaphor does not have a top-down directionality to it also makes it suspicious to those who are fully within the top-down TBM tent.

(1) is about the suspicion that intellectuals in general should have to OP, while (2) is about the additional suspicion that TBM’s should have to OP. The two objections are not incompatible with each other, and I apologize confused people by conflating them.

To apply my objections to myself, my objections (a) presuppose a standpoint outside of the TBM tent but within the tents of communitarianism, pragmatism, critical theory and social epistemology; and (b) advocate entering more deeply within the TBM tent. Thus, I presuppose top-down authority in the position that I advocate -(b)- but not in the position that I presuppose -(a)- when I advocate for (b). Like I said, you’re right, but only partially right.

Jeff,

You often argue historic top down models as having creditability mostly because they existed first and then you draw parallels to scripture that seem to support top down models implying some sort of superiority to them. But this isn’t a creditable argument anymore than arguing for the return of slavery based on precedent and Biblical support. You are repeatedly placing the brethren between the members and God himself with follow the prophet admonitions when following the spirit is much more direct and far more useful for those who can hear him. Your model is not superior to direct divine or spiritual experience.

“But this isn’t a creditable argument”

I agree. That’s why I never made it.

Mine is about what kind of society the scriptures presuppose, not what kind of society we ought to advocate. Now you’re the one who’s conflating the (a) and (b) from #27.

Jeff,

The scriptures cannot escape the top down society they were in when they were created to presuppose another society without including bias.

What are you talking about? Not only have I never believed that, but it falls WAY too far afield of this thread.

On that note, I don’t think I’ll be able to articulate my objection to the OP any better than i did in 27, so I’ll just bow out at this point.

Sorry for the long-winded, partial thread-jack, HG.

If a tent is a metaphor for a family (or a church), with parents (or prophets and apostles) at the center and children (or supplicants) at the periphery, it makes sense to look inward for guidance and direction. Continually looking outwards (especially while insisting on wearing rose-colored glasses) and unkindly judging those further inside causes dissonance. But with time, we hope these things work out.

I don’t know where I’m at but it isn’t very close to the center of the tent. I have a most unusual privilege since my wife decided to attend a evangelical church. I take her to an LDS service and she takes me to an evangelical service every week. This has been going on for many years now and both feel sort of like home.

I have serious issues with evangelicals- a long list: trinity, infallibility, infant baptism. paid ministry, judgmental etc. etc. I read the actual words of Luther, Calvin, Edwards, etc. and they sound insane. I don’t think I can be anything more than a guest and friend.

But I am so tired of going to my church each week and seeing what a crappy job we do. The music is horrible, the prayers are vain, heartless and repetitious, and half the talks a waste of time. The youth programs are lame and we do very little service of any sort. I think a few people at the top actually care but most really don’t act like it is anything except a burden. If church was a restaurant we would be dishing out really bad fast food served cold.

I like the idea that different people have different expectations and needs from church.I suspect many people love attending my ward. (One of the plays right out of the apologetic playbook is blame the messenger of any criticism and maybe it is mostly my fault). But I am having trouble finding which of the three fits me.

Physical Infrastructure to serve others. Maybe, one upon a time. I was an EQP twice for total of 10 years I lost my testimony of home teaching. I felt the need to repent of home teaching. Too much trouble and damage done for too little good accomplished. I have been in boy scouts in both a LDS troop and non-LDS troop. No comparison, not even close. Our LDS troop needs to be disorganized and the youth join other troops in their neighborhood. About the only service available to people like me who only attend 1 hr a week and work every other weekend and have free thinking tendencies is janitorial service. I don’t have the vision of it. I’m not fitting in here. Maybe others do.

Cultural relationships. I was raised in rural Utah and I am very much a tribal Mormon. And Mormons can be a very nice tribe. To potential converts we are often nothing short of charming. To members we are like family but we have high expectations of conformity and tattle on each other and can’t keep our noses out of everyone’s business. To those who have left and seem to have left for good, well that is another story in far too many cases. I have LDS friends, but the friendships are shallow. Then they divide the ward and put about 90% of them in the other ward and the others were not that strong in the first place.the current ward is mostly young transient people who are about the same age as my grown children It leaves me feeling isolated. Closer here but still not cutting it.

Intellectual infrastructure. You have got to be kidding. Other than the internet the only real Mormons I know are clueless about fundamental problems (with maybe one or two friends). Here is what passes for intellectual thought. Joseph Smith was a monogamist. Thick books filled with archeological evidence of the Book of Mormon are out there somewhere. The book of Abraham is pretty short, maybe we mention it twice a decade. Gays, to hell with them. Women’s issues- what issues they are all perfectly happy. Milk before meat. (Sour watered-down milk). Maybe this works, on another planet closer to Kolob.

Perhaps we could come up with three more aspects including one that might help me feel less like the man without a country when it comes to religion.

Hawkgirrl, this is one of my favorite posts ever.

I definitely experience cultural clashes. I hang out near the edge of the tent, a safe distance from those at the center who are all in for everything. It’s not that I want to drink wine or go out to eat on Sunday. I just want to get away from those who listen to conference, looking for new observances to put on their to-do list, or those who sit through a Homemaking meeting on extreme Word of Wisdom ideas and believe we’re all obligated to shun margarine and white flour from now on.

Being at the edge of the tent has nothing to do with rejecting prophetic counsel. The edge is a place to think things through, sort out the real counsel from the junk and live in peace, a safe distance from people so anxious about getting it right that they drive themselves and the rest of us nuts.