The Tree of Life and the Great and Spacious Building:

A few years back in Sunday School, we were dissecting Lehi’s dream in 1 Nephi 8 when someone in the ward posed a question that landed like a small theological grenade. Lehi raves about the fruit—“desirable,” “sweet,” soul-filling. So she asked, If it’s that good, why isn’t everyone sprinting toward it? And why do the people who actually reach it still walk away?

Our reflex, of course, is to run back to the text for quick answers instead of letting the questions unsettle us. The vision itself offers convenient explanations—stony ground, a weak grip on the rod, the shaming voices from the great and spacious building, even the devil waiting in the wings. But those explanations tend to assign blame rather than invite curiosity. They push us to explore the horizontal width of the story, its surface-level moral geography, while quietly steering us away from the vertical depths where the real human questions live.

That question has refused to die. In fact, it’s forced me to rethink the whole vision. Maybe Lehi wasn’t sketching a cosmic obstacle course at all. Maybe the iron rod, the mist, the wandering crowds—none of it is about sorting the righteous from the wicked. Maybe it’s a portrait of the inner landscape we’re all navigating, a map of the self that’s far messier than any Sunday School chart will admit.

And if the tree is, as Alma later suggests, something planted inside us, then the shocking truth might be this: you can stand “at the tree” and still be starving, because nothing external can substitute for what hasn’t matured internally. The people who leave the tree aren’t rebels—they’re human. They’re us. The whole vision stops being a morality play and becomes an invitation to grow something real inside, something no institution can hand you and no checklist can guarantee.

Lehi’s vision of the Tree of Life is often read as a oversimplified prescription, complete with a point A to point Z list of things to do and others to avoid: the righteous go toward the Tree; the wicked enter the Great and Spacious Building. But beneath the surface of righteousness and wickedness lies a more universal human dynamic—one that every soul experiences regardless of belief or background. It is the struggle between competing desires.

On one side is the desire for connection, intimacy, and rest—the desire to stand at the Tree of Life, where God’s love flows without condition. On the other side is the desire for safety, self-protection, and control—the impulse that draws us to the Great and Spacious Building. These desires live within each of us, pulling us simultaneously toward exposure and concealment, toward vulnerability and image, toward the courage to be known and the comfort of remaining hidden.

The Tree of Life: The Desire to Be Fully Known and Fully Loved

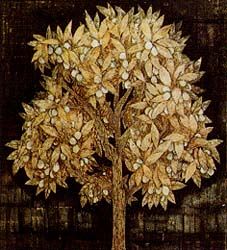

The Tree of Life represents a place where love is not earned but freely given—a place of pure presence and belonging. It is no accident that the imagery surrounding the Tree echoes the Garden of Eden, where humanity was once naked and unashamed. To stand at the Tree is to return to that posture of openness before God and one another.

And yet this openness is precisely what makes the Tree so difficult to approach. The light that emanates from it is not merely bright; it is revealing. It shines through every layer we use to protect ourselves—our accomplishments, our curated identities, our emotional armor. Nothing can be hidden in that light. For those of us who have learned that transparency is dangerous, who have survived by concealing their wounds, this exposure feels unbearable.

But this same light also heals. In its radiance we find the deepest desire of the human heart: to be seen exactly as we are—afraid, imperfect, and unfinished—and still held with unwavering tenderness. To stand at the Tree is to experience the paradox of grace: that love grows strongest not where we are strong, but where we are vulnerable.

This desire, the desire for intimacy and acceptance, is ancient. It pulses beneath every longing for belonging, every search for meaning, every ache for connection. It draws us quietly toward God, even when we fear being seen.

The Great and Spacious Building: The Desire to Be Safe and in Control

Yet standing in direct competition with this desire for intimacy is another desire equally human and equally strong: the desire for safety.

The Great and Spacious Building offers precisely that. Elevated above the ground, it provides distance from vulnerability. Its walls shield us from exposure, and its crowded halls drown out the fear of being truly known. Here, identity can be managed. Here, we can clothe ourselves in achievement, reputation, and social belonging. Here, we can avoid the discomfort of being seen fully while still appearing to belong.

The building whispers that love and acceptance must be earned—that value is tied to performance, refinement, and presentation. It offers admiration instead of intimacy, applause instead of understanding. And for many of us, perhaps me most of all, that feels safer than the nakedness required at the Tree.

This desire for safety is not inherently wrong. It is a form of self-preservation learned from a world where vulnerability often leads to harm. We build walls not because we are weak, but because at some point we were wounded and learned that walls keep out pain.

Yet these walls that shield us also isolate us. They offer protection at the cost of connection. And so the building becomes both refuge and prison—promising belonging while keeping us far from the very love we long for.

The Magnificent Tension: Desire Competing With Desire

Lehi’s vision is not a simple story of good versus evil.

It is the story of the divided human self.

- The heart longs for the Tree—longs to be known and loved.

- The mind longs for the Building—longs to be safe and in control.

Every day we navigate this tension.

We want intimacy, but we fear exposure.

We want love, but we fear what it might reveal.

We want God’s presence, but we fear God’s light.

And so discipleship becomes less about choosing between righteousness and wickedness, and more about choosing which desire we feed: the desire for safety that keeps us hidden or the desire for love that draws us toward healing.

Bearing Glory: Choosing Vulnerability Over Pride

The essence of pride, in this context, is not arrogance. It is the belief that love is earned—conditional, fragile, and dependent on our performance. Pride convinces us that if we were truly seen, we would be rejected. It keeps us clothed, even in places designed for nakedness. It keeps us polishing the image in the building instead of walking toward the light by the Tree.

To “bear God’s glory” is to allow ourselves to be stripped of this pride. It is to step into a love we cannot control or earn. It is to let the light pierce through our defenses and discover that what is revealed is not condemned but cherished.

This is why the Tree is both beautiful and terrifying. It confronts our deepest fear: to be known.

And it satisfies our deepest desire: to be loved.

The Journey Between Two Worlds

Ultimately, Lehi’s vision invites us to recognize the internal landscape of our own souls.

Not to shame our fear of vulnerability, but to understand it.

Not to condemn our desire for safety, but to notice how it competes with our desire for love.

The journey to the Tree of Life is not a straight line. It is a gradual surrender of the walls we built to survive, a slow movement from hiding to openness, from fear to trust. It is the practice of believing that love precedes worthiness, that God does not turn from our nakedness but calls us gently out of hiding.

The Great and Spacious Building is loud, impressive, and compelling.

The Tree is quiet, humble, and deeply brave.

Both desires are real.

Both are human.

But only one leads to rest.

Discussion prompts

I’m going to leave this one open, go wherever it takes you.

Thanks for this Todd.

I truly appreciate your description of The Tree, what it’s like to be there and what it can do for us from an eternal perspective. I have never had a more beautiful description of it painted in my mindscape. I love that, and am truly grateful for your words regarding it.

As to the building, I also appreciate that you have been very personally open and identified the aspects of the building that draw you to it. That is some serious courage there brother! But I also want you to know that your courage in doing so, has caused me to ponder the things that are in the building that draw me to it, particularly the things that keep me from the benefit of resting in the shade of the tree and enjoying some particularly “good fruit.” I don’t have the courage to identify those things, nor the space to do so, but your description causes me to consider that we all have things in the building that we want, and we need to recognize that. It is different for everyone. The building is beyond the best shopping mall that you have ever been to with the ease of Amazon! 😁 The best food, clothing, entertainment etc, and, it provides escape. The trick for all of us, is that we need to realize that we all want something that is in the building, often at the cost of the the perfect love and peace at the tree.

BRAVO Brother for prose that is a truly wonderful description!

Cheers – Mongo

This post made me think about that story and I found the ideas to be IMHO to be challenging and exciting to me. I wonder if someone were to put forth the concepts presented here in a regular Sunday School Clas or Elders Quorum/Relief Sociey lesson what kind of reaction and/or discussion that would create?

This is wonderful and resonates with me, but you found words for it.

There are those though, who have no desire to be known. And they are many, not few. what are we to make of those

I wonder. I conclude that it is not my place to judge them. I think something probably went deeply wrong as their brain developed, or perhaps their brain architecture is other than my own. Are those the same thing? They can really bust up your path if you have eternal commitments to them though. The path is not clear when accompanied by them.

Great post. I love the notion of the divided self, because that’s really what we are and, IMHO, we get farther from knowing our true selves if we don’t acknowledge our own complexity. The idea of not wanting to be known/not being known echoes profoundly through Elizabethan tragedy, not just the B of M. Hamlet isn’t a play about murder, revenge, or the righteous anger of a disinherited son; it’s about the tragedy of loneliness that occurs when we don’t (or we feel that we simply can’t) trust each other. The best definition of tragedy that I’ve ever read was from the philosopher Stanley Cavell. When commenting on Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, he said that at its core, tragedy is caused by “the refusal to know and to be known.”

This is a profound and moving post. It gets at the core of the human dilemma; one that we’re all trying to work out along our way. One hopes we’d be more open/vulnerable and less closed/controlling, but neither human history nor the B of M (a book I consider fiction) offer much hope; it’s worth noting that the supposedly inspiring, joy-producing B of M ends with utter destruction and violence. To your point, I think the book provides other avenues, but it certainly doesn’t hold out much hope for humanity; it, like Elizabethan and Jacobean tragedy, seems to suggest that most humans make choices that end up alienating/destroying other people rather than inviting them closer.

It seems better to look at the dream this way. Every one of us during our sojourn in the land faces everything that Lehi saw in his dream.

This way of looking is far better than an “us” versus “them” mindset.

I love this way of thinking about this story. Far to many parables are told in a way of the “in” group and the “out” group like @ji mentions above. Parable of the talents. Wise man and the Foolish Man. Parable of the 19 Virgins. Wheat and the Tares.

The parable of the Wheat and the Tares has been on my mind a lot lately. It’s easy to talk about “sifting” while skirting around the fact that it’s own family and friends being “sifted” No where in the parable are the tares burned! but we treat them like they are burned with the field.

The first law of heaven may be obedience, bit the first law of earth according to Jesus is love. Maybe we should focus on the love part more while here and the obedience stuff will make more sense to us there.

*Edit* Apparently the tares are actually burned in Matthew, but we can still interpret this in a way that doesn’t assign whole people to destruction. Wheat and tares could represent our own good and bad sides within a single person! We can burn the parts of ourselves that hold us back, while nourishing the already good and lovely parts of ourselves. Feels better right?

Sylvie, agreed! Scripture, IMO, was never meant to be read as “Orthodox” (one opinion), this takes the stories, and like lava, calcifies into rigid obsidian. Lest we forget, “spirit” is always understood scripturally as “movement”, “water”, “wind”, “fire”, the Hebrew word being “Ruach”, which is feminine word. The spirit of a parable is that which gives it life, makes it feel alive and animated. We always reduce these stories to “structural” maps, which necessarily strips them of their “movement” (spirit).

Also, the message of Jesus is a constant plea to expand hospitality, to eat with people you never would, to touch people who were labeled “unclean”, NOT to sift, but to gather. The sifting, whatever that means, is not the job of the humans.

My son went to camp Helaman and came back disillusioned and angry about several things. The “iron rod” exercise was one. Before it, they talked about the way to cling to the iron rod. One of the recommendations was “listen to your church leaders”. So, they were blindfolded and given the rope to hang onto. So, three or four of them listened to the voice of their YM’s leader telling them to stay where they were because there was a problem they were trying to fix in front of them. So, they stopped and waited, then this announcement comes that if they are not at the “tree,” they blew it. They made the “mistake” of listening to the voices trying to “lead them astray.” They made the mistake of trusting and doing as they were told by the leader they had been told to trust. So, it was obedience to church leaders that got them screwed. They all felt lied to and betrayed because they did as they were told and listened to the church leader who was really the bad guy leading them astray.

Hmmmmm, sounds like the exact experience of many of us who have decided that church leaders are most certainly not inspired and by listening to them we are really cheated out of listening to our own inner voice.

There were some other problems like the guys he had to share a cabin with who could not be trusted and lied to get others in trouble so they could look good to leaders. Another “inspirational” exercise that also blew up into a lesson in not trusting. So, he came home learning real life lessons in “trust no one,” especially if they tell you to trust them.

I really did not know what to tell him about the whole experience when something is supposed to be inspiring and teach good principles and backfires and ends up disillusioning teen aged kids and making them question their whole testimony because human leaders screw up the learning process by making people who are supposed to be trusted into the bad guy. It was much too much like real life. He went inactive for the rest of his time in YM.

So, my thoughts on your interpretation of Lehi’s dream? I guess it has to be about how I am not about to trust your ideas either😉

It has never been something that I could relate to. I suppose I have always been more of a Liahona Mormon. I can see following an inner compass that brings you back to God. Never could see hanging onto something that drags you through a swamp.

Hanging on to the word of God is the key. And 3rd Nephi chapter 19 shows us exactly what happens if we don’t let go.

Lehi’s dream is based on the same dream experienced by Joseph Smith Sr. It also has two versions which are confusingly inconsistent. That doesn’t mean it can’t be interpreted in a helpful way and mean whatever you want it to mean. I used to try to do that.

It seems to me that extroverts will be more comfortable in the building and introverts at the tree.

Jack — I see where you’re coming from in the context of LDS tradition, but I’d really enjoy hearing you expand on your point. In ancient settings, scripture functioned as an entry point into the mysteries—an invitation to wrestle, question, and explore.

In modern LDS culture, though, certain phrases like “hanging on to the word of God” tend to invoke well-worn doctrinal narratives that can actually prevent deeper engagement with the text. I’m curious how 3 Nephi 19 shapes your view here, and what nuances you see that go beyond the familiar patterns.

Hi Todd S. Thank you so much for the thoughtful framework. I have always liked Lehi’s dream-vision better than Nephi’s. It seems really, really important to Nephi to ascribe a singular meaning to everything. That can be, I’ve been given to understand, a trauma response.

Lehi, on the other hand, seems a bit more comfortable sitting with ambiguity. It’s hard to say for sure, though, because we are seeing him through his son’s lens.

Anyway, Todd, I like your reading of the tree and the building. It resonates. The thing that I suppose I struggle with most in looking through the dream-vision through this lens happens on Nephi’s watch in 1 Nephi 11:36. I’ve never particularly liked that the building falls. Okay, yeah, these people were making fun of people who were living the(ir) truth, and that is a terrible thing to do. But the consequence seems very disproportionate, no matter how I read the story.

But when I apply your lens? Then these are just people who were scared to be vulnerable, and now 11:36 is positively monstrous.

I am scared to be vulnerable all the time. I see and use my professional and academic accomplishments as comforting, insulated walls against judgment. When it comes to being truly seen, in the words of Bartleby the Scrivener, I prefer not to. I love my fellow humans, but I reserve the right to love them from behind the walls sometimes (oftentimes?).

And, maybe this is heretical, but I think that’s legitimate. We need our orchards and our high towers. At least I do.

Todd S,

I think the Book of Mormon provides a multilayered definition of “mysteries.” The most basic definition would be anything that can only be known by revelation–and that would include the preparatory gospel. We wouldn’t know anything about the most basic elements of the gospel if the Lord hadn’t sent angels to teach it to Adam and others who came after him. And then there’s a sense (in the BoM) of those mysteries that must be guarded with care. And finally those that are beyond comprehension.

With that in mind, when we’re talking about something like the iron rod (the word of God) I think that image can be useful regardless of how we approach it vis-a-vis the “mysteries” as I’ve explained above. But even so, the BoM does give us a view of what might be considered a more esoteric definition of “the word” in 3Ne 19. It’s not something that should–or even can–be spoken of freely. And that’s why Mormon paints a wonderful picture of that miraculous event–and then let’s the reader discover what it all means on their own.

This is very thought-provoking. I went back to the BoM and reread the vision after reading your thoughts. The woman in your Sunday School class asked a good question. Not only do some people not want the fruit in the first place, but some who partake of the fruit then become ashamed of it if they heed the mockery from the great and spacious building. So is the fruit that wonderful for everyone, or did Lehi have a subjective experience with the fruit? Perhaps not everyone experiences the love of God to be something that fills their soul with joy. As you note, some can stand at the Tree and eat of the fruit and still be starving.

Like Margie, I have walls that I’ve built for protection. I know that they’re there; I know how they affect me; I know why I built them. My experience at the Tree was with taking down the internal walls and getting to know, love, and accept myself. God’s love was there too, though I now interpret God differently. Self-acceptance and unconditional love was the fruit that filled me with joy.

I can understand why some reject self-acceptance. In some situations, it’s a lot safer to reject some aspect of yourself just to survive and function in society. As society gets more cruel towards transgender people, I imagine some of them will choose to reject their gender truth. Their fear is justified. Like, hiding aspects of yourself from other people is sometimes the smartest thing you can do. But not from God. That’s the point you’re making, isn’t it? The Tree is taking down the walls between our inner selves and God.

Margie and Janey – Thank you both for additional insights that help me see other really important aspects.

Margie, your comment only deepens my conviction about just how complex the human condition really is. And Janey, yes, that is what I mean. My hope is that everyone feels what it’s like to be loved for more than their performance—for more than just their polished, presentable parts. I hope they taste the majesty of Grace, the kind that embraces the whole self, weaknesses and warts included.

Those very weaknesses—exposed by the light of the tree—are so often the things I’m ashamed of, the things that send me back into hiding. But they’re also the places where genuine connection becomes possible.

And I don’t believe the intimacy of the tree is reserved only for God. My hope is that everyone finds at least one human relationship that reveals this same depth—a love spacious enough to hold the full truth of who we are.

I don’t see the building and the tree as mutually exclusive. There are relationships in my life that remain necessarily partial, structured, even guarded—and others where I’m slowly learning to share the vulnerability of mortality. Both are real. Both serve a purpose. What I’m resisting is the false demand to choose—to sanctify one and condemn the other. I’m no longer interested in murdering half of myself in the name of holiness. I’m trying to learn how to hold both: to live in the world with its protections while also risking the tenderness that makes life worth living. Integration, not eradication, feels closer to the truth.

And this is where I struggle with the traditional LDS reading. It quietly turns the tree away from intimacy and into performance. The fruit becomes a reward, not a gift. In that move, the tree is effectively relocated right into the center of the building. Religion—meant to interrupt the ego’s games—often ends up reinforcing them. Instead of offering rest, it sanctifies striving. Love becomes something to qualify for, worthiness something to achieve. The symbol meant to free us from performance becomes another metric, another way to prove that I am—or am not—enough.

To say it plainly: if Nephi’s interpretation rests on a simple binary, I don’t think his father agrees—and neither do I. The tragedy of that binary is that it sets our humanity against divinity instead of inviting their integration. When Jesus says we do not live by bread alone, the point isn’t to demonize bread. It’s to warn against bread without relationship—survival without sharing. Materialism fails to answer the deepest questions about our lives, loves, and longings. There are hungers too big for bread to satisfy,

I’ve spent much of my life trying to outrun my humanity, shaped by a story that implied the goal was to abandon the building entirely. And like everyone, I carry a deep desire to matter—to be liked, admired, seen as good. The problem has never been those desires themselves. It’s the belief that love must be earned through flawless performance.

I don’t think the invitation is to eliminate the building or deny our defenses. The danger is spending a lifetime trying to prove I am perfectly lovable and missing the chance to be known. I need to matter, and I need the tenderness of the tree. Both are human. Both are reasonable. The trouble comes when I tangle them together—when I insist that intimacy can only come after I’ve proven my value.

The irony I keep returning to is this: the deepest love arrives precisely when I stop treating weakness as the problem and begin to see it as the doorway to the tree.

Fascinating post. I’m not sure you can conflate Lehi’s dream with Alma’s vision. Also, the “word of God” if defined as scriptre includes many passages that condone slavery and justifies rape, among other things, but if it were considered to be the Word of God, or love personified, that could lead us to the tree of life, which is defined as “the love of God, which sheddeth itself abroad in the hearts of the children of men; wherefore, it is the most desirable above all things.” Interestingly, it does not exclude anyone from receiving that love, but the people in the great and spacious building, who were clad in fine apparel and mocked others, excluded themselves.

Mormon warns us today: “And I know that ye do walk in the pride of your hearts; and there are none save a few only who do not lift themselves up in the pride of their hearts, unto the wearing of very fine apparel, unto envying, and strifes, and malice, and persecutions, and all manner of iniquities; and your churches, yea, even every one, have become polluted because of the pride of your hearts.

” For behold, ye do love money, and your substance, and your fine apparel, and the adorning of your churches, more than ye love the poor and the needy, the sick and the afflicted.”

In 4 Nephi, we see the dissolution of a godly society as people divided into contention groups, people “were lifted up in pride, such as the wearing of costly apparel, and all manner of fine pearls, and of the fine things of the world,” and “they began to build up churches unto themselves to get gain.”

Lehi’s dream is an account of God’s unfathomable love and a cautionary tale for all churches and people who value pride, wealth, and fame more than helping those in need.

As Jesus taught, the final separation of the righteous and wicked will be those who fed the hungry, can the thirsty something to drink, invited in the stranger, clothed the naked, cared for the sick and visited the prisoners, and those who refused to do so.

Thanks, again, for a thought-provoking post.

Very good post. Thank you for posting it. I guess that I have been caught up in the quick answer as to why people left the tree without thinking “Hey, Lehi described this as the best. Why are they really leaving?” I certainly will think about this more.