Jesus’s most common refrain— “come, follow me”—seems innocent and direct, more motion than thinking. But it carries a problem baked into the phrase itself: Jesus is said to be perfect. Whatever “perfect” means, the implication is that he possesses characteristics and capacities that are, in some sense, superhuman.

Marcus Borg captures this tension well:

“A figure who has superhuman powers is ultimately not one of us. Jesus’ humanity disappears… If Jesus had superhuman power and knowledge, he cannot be a model for human behavior.”

So, what do we make of this? Can someone genuinely invite us to follow what we are fundamentally incapable of achieving? It’s like telling someone born without arms that they will someday be the greatest quarterback in history. What are we supposed to do with the radical commands Jesus offers—love your enemies, bless those who curse you, forgive those who harm you, seek justice, eat with sinners? Are these not beyond the reach of mere mortals? Scripture complicates this more by insisting Jesus “grew in wisdom and stature,” while Christian tradition claims he was perfect. Perhaps “perfection” meant something different in their world than ours.

LDS theology adds another layer with its emphasis on theosis—becoming like God—a doctrine often derided outside our tradition but deeply woven into our own. The refrain persists: we must become more like the Savior.

But how?

And perhaps more poignantly: how much like something we fundamentally are not can we actually become?

Telling people, they can accomplish anything if they try hard enough makes for good motivational posters but eventually collapses into soul-crushing psychobabble disguised as hope. Inviting frail, inconsistent mortals to model their lives after a superhuman Christ is like asking a five-year-old to go out and break the world record in the long jump. The point is not to dismiss the possibility of transformation, but to question the paradigm itself. Either Jesus is far more human than we’ve been willing to admit, or humans are far more divine than we’ve dared to believe. Without reimagining one—or both—of these categories, the injunction “come, follow me” becomes little more than a naïve slogan at best, and religious manipulation at worst.

If the old paradigm collapses under its own weight, the answer isn’t to throw out Jesus’s invitation—it’s to rethink the categories that made it feel impossible in the first place. We can’t keep pretending Jesus floated above real human experience, and we can’t keep treating humans as if we’re spiritual zeros. Both distortions create a kind of discipleship no one can inhabit. The gospel writers actually give us another picture. They show a Jesus who eats, grows, learns, gets tired, feels fear, weeps with friends, and prays for strength. In other words: someone real. Someone human. His life isn’t impressive because he was superhuman—it’s impressive because he was fully alive within human limits.

St Irenaeus captured this sentiment around 130 AD: “The glory of God is a human being fully alive”

Jesus lived with a clarity and compassion that came from deep alignment with God, not from cheating the system.

And that’s the point. If Jesus reveals what a fully open human life looks like, then “come follow me” is not an absurd expectation—it’s an invitation to rediscover capacities we’ve forgotten. We aren’t told to match his power; we’re invited to walk his path. The radical teachings—love your enemies, forgive freely, sit with sinners, seek justice—stop being heroic demands and start functioning like spiritual practices that shape us over time. They are directions to grow in, not bars to clear. This reframes theosis too. Becoming “like God” is not about ascending to superhuman status but waking up to the divine image already in us. Jesus doesn’t stand as the solitary exception; he stands as the clearest expression of what humanity aligned with God can look like.

I know that reducing Jesus to nothing more than a “great moral teacher” is considered heretical in orthodox circles. But looking across the history of myth and religion, the most striking thing about Jesus may actually be the combination of his radical wisdom and the claim that God became human—not as a disguise, but as a revelation. Jesus isn’t a guru dropped in from above; he is the symbol of God in human form; meant to show humanity who we really are and what we’ve always been capable of becoming.

So maybe the most divine thing about Jesus is that he became one of us—completely. Not to shame us, but to remind us. Not to tower over humanity, but to awaken it. And perhaps his title as “Savior of the world” has far less to do with satisfying some cosmic demand for penalty and far more to do with offering a life worth imitating—a life that dismantles the barriers in our minds and opens us to far grander possibilities.

Questions for discussion:

- If Jesus is portrayed as both perfect and genuinely human, what kind of “perfection” makes his life followable rather than impossible?

- When Jesus says “Come, follow me,” do you experience it as an impossible ideal, a transformative path, or something else entirely? What shapes that perception?

Todd – isn’t much of the tension re “perfect” discussed in this post addressed by recognizing that the scriptural injunction in question was originally recorded in Koine Greek as (τέλειος) and then exploring how “perfect” is a pretty terrible choice of word for the translation?

Great post BTW.

Lovely post, thank you for sharing. I’m studying a book called The Way of Mastery and this is the basis of what it teaches. We are all divine beings and Christ lives within each one of us. I believe the second coming of Christ is when we wake up and and realize that there is no separation and we are divine. I think it’s individual not collectively. “Jesus isn’t a guru dropped from above; he is the symbol of God in human form; meant to show humanity who we really are and what we’ve always been capable of becoming.”

Great post, Todd. Very much enjoyed it and provoked to thought by its ideas. I think “Come, follow me” is achievable, in part because it does not communicate a completion or attainment. To me, that phrase invites me into an ongoing process, a way of living. And that strikes me as totally achievable in this life. Yes, that’s a subjective assessment, but perhaps it needs to be.

The word that kept popping into my mind as I read this post was aspirational. And that begs a question as you point out: is it good to aspire to something we may never achieve: perfection, Godhood, purity, whatever? I think it can be, especially if we see following Jesus as an ongoing process, not as a pass or fail assignment. We can expect to be always and ever making refinements and course corrections.

Another word in Christianity that leads me to the same basic idea is “mystery.” Mystery’s constant presence, just beyond our perception and understanding, ensures that no matter how much contemplation and worship we do, we will always have more ahead of us to pursue. That can feel frustrating, like a tease. But its virtue is that it guarantees we will always have purpose in this life when we are following the Lord. Whatever we aspire to—solving a holy mystery or achieving a fully Christlike state of being—in our finite imperfection, we will always have a reason to wake up each morning and continue following.

“When Jesus says “Come, follow me,” do you experience it as an impossible ideal, a transformative path, or something else entirely? What shapes that perception?”

I don’t know about others, but I think most of us that are trying to follow Christ will likely face this juncture sooner or later – the initial understanding/belief that leads to feeling like it is an impossible ideal, but hopefully further experience and understanding help to get past that juncture to the transformative attitude and orientation that helps us to do as you describe:

“We aren’t told to match his power; we’re invited to walk his path. The radical teachings—love your enemies, forgive freely, sit with sinners, seek justice—stop being heroic demands and start functioning like spiritual practices that shape us over time. They are directions to grow in, not bars to clear.”

I believe that the injunction is to focus on the practice that shapes us over time, with the acknowledgement that they are not bars to clear expressly because of Jesus’ atonement. We do not become perfect because of the spiritual practices over time, rather we learn and grow and know that it is the atonement that makes us ultimately complete and whole, and at one with God again.

Yes, “perfect” is a bad/wrong translation, but it is what the church teaches anyway.

Nor does Come Follow Me mean ‘follow a perfect Christ’. It means Follow The Church. Period. Whatever

they tell you is right, and you are never allowed to criticize. If they get something wrong, the blame always goes to the highest authority, meaning God.

“If you wish to be perfect, go, sell all you have and give the proceeds to the poor, then you will have treasure in Heaven. Then come follow me.’

But…but…but…

I issue my strongest possible condemnation to the way the concept of “perfection” has been mistaught. It has caused great harm.

The Savior did not speak English when he was alive and well. The word “perfect” is a mistranslation. The word he actually used is more accurately translated as “complete”. To be complete does not mean to be without blemish, it means to be whole or in balance. A state of completeness includes some blemishes.

The Savior never commanded anyone (in his native language) to put enormous pressure on oneself to be completely without blemish. He actually commanded his followers to be whole, meaning to have a balanced life. That does not mean that one is free to behave like a depraved Russian princess. But it does mean that one can do one’s best and not have to be overcome by guilt.

John Charity Spring has turned me into a Dua Lipa fan and an aficionado of Honky Tonks. Now I’m having nightmares about depraved Russian princesses. The man has no limits.

OK, so I had a long comment asking about whether Mormons even know what the hypostatic union is…? and then I realized, “probably not” and “actually, the way that Mormons reject the hypostatic union makes this post kinda not make any sense.”

But I then realized that there’s probably a much shorter way to try to summarize all of these things.

In traditional Christianity, there is a vast and irreconcilable divide between creation and God. This isn’t just a matter of the Fall — it’s fundamental to the differences of our natures. God is uncreated, creation is…well…created. You can’t ever bridge that gap. I think that this is probably where Todd is going with the “superhuman” themes throughout. (I want to quibble about that as a description of Jesus, but whatever, maybe I’ll write a different post about the hypostatic union to avoid hijacking his comment section.)

But to get at probably a stronger verse to make Todd’s point in traditional Christianity might actually be Matthew 5:48 – “Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect.”

Like, whoa, how is that possible?

The conventional understanding is that everything is intended to be related by analogy. Like, God sends rain and sun on the just and unjust alike — he is impartial in bestowing these blessings. Being perfect as the Father is perfect doesn’t mean that we are supposed to develop The Weather Paradigm and make sure that rainfall patterns are the same between our pact brethren and those with whom we have declared vendetta (5 points to the first person who gets this reference).

No, it means in our sphere *as humans*, we “complete” our “purpose” or “end” as humans by being impartial in our treatment of others in our spheres *as humans*. (And yes, as many others have addressed in their comments, the word teleios in Greek that we translate as “perfect” has a lot of different flavors…it’s more like directedness to a goal, maturity into what one was meant to be, completion.)

OK, but I did want to get at my issue. The issue is that Mormons do not create a vast and irreconcilable divide between creation and God. Humans are either as uncreated as God is, or God is as “created” as humans are. This gets to that “As man is, God once was. As God is, man may become.” Do Mormons believe this at all anymore??? I am vaguely aware that it’s been deprecated and not just in the “wink wink” way to outsiders who aren’t ready for the deep lore.

So, in this sense, Jesus certainly isn’t a superhuman. Or, rather, if he is superhuman, so are we.

I think of portrayals of superheros. Especially in modern times, it’s very popular to portray that even with all those fantastic powers, superpowered humans are necessarily morally superior, or even all that morally good, as examples of humans.

I’m not trying to say that Jesus is Homelander from The Boys…just…in a system that sets up that we’re all essentially the same species, we need different answers for why some people use their talents and gifts for good purposes and others…not so much.

Like, what is the excuse in a system where Jesus actually isn’t a superhuman, or rather, you’re also a superhuman. What’s your excuse for not living up to your potential now?

I think there are two things happening: not only do we follow the Savior–we also come to him. In John chapter 10 he describes himself as both the Good Shepherd and the door of the sheep. In Mosiah 5 the saints are called by the Savior’s name and he is the one who calls them.

And so I think the Savior brings us along as we strive to follow him. When we receive grace for grace we are then empowered to move from grace to grace. And so not only do we follow the Savior like chicks follow their mother hen–he also gathers us like a mother hen under her wings for protection.

Sorry for all of the little analogs–I don’t know how else to describe it.

I’m going to follow up on JCS’s observation that the word that was translated as “perfect” actually means “complete” or “whole” mainly because I have a great anecdote of something I never did. If I’d had the chance to teach this lesson in Gospel Doctrine years ago, then I would have brought my young son (less than 8 yrs old) into the classroom and said, “this child is perfect in the same way Jesus commands us to be perfect.” He is who he is meant to be, whole and complete. He throws fits and has overreactions; he finds joy in being himself and bestows love on other family members. He eats food, and either digests it or throws it up. He still has the occasional bathroom accident. He has opinions and tests the boundaries between himself and other people. He makes messes; he cleans up after himself imperfectly because he’s just a little kid. I love him; I get exasperated with him; I want to cuddle him at bedtime; I wish he’d get dressed faster; I was so excited that he was excited when we went to the zoo; I am so done with him fighting with his brothers.

It made me think about what ‘perfection’ (completeness) looked like for a single mother of small children. I’m exhausted; the house is a mess; my kids had fishy crackers for lunch; I am so tired of diapers; my kids climb into my bed in the middle of the night if they have a nightmare because they know I will comfort them; I taught them all to read before kindergarten; they look so cute in their new Church clothes!; when is the last time I got to read a book?; I’m not cleaning marker off the walls anymore – who even cares?; sometimes I hurt when I look at them because I’m so scared that life might hurt them; my heart is walking around outside my body; please just let me go to the bathroom; he smiled! look! my boy is happy!; I now understand why sleep deprivation is considered torture; is it bad to think about putting your kids in foster care just to get a break?; is there anything more fun than watching your kids have fun?; motherhood is so overwhelming; I love these kids so much.

That’s how I try to think of the “be perfect” admonition anymore. Be who you are supposed to be.

About the theology in this post (and let me just say this was a thought-provoking post). I’ve also wrestled with the command to try and use God and Christ as examples. It started back when I got confused by instructions to follow the examples of the apostles and Church leaders. I’m not a married straight man with a lot of charisma who is known by millions as a leader and an example. Once I sorted out that I cannot follow the example of the Church leaders, I started thinking about what it meant to be like Christ. It’s physically impossible. I am not a 30-year-old man with 12 close friends and the ability to turn water into wine. But I follow his teachings as best I can. I feed the hungry. I process anger and release it rather than holding grudges. I think kind thoughts towards people who live their lives differently than I do. I help when I can.

As a faithful Church member, I saw this verse as possible if I just had enough faith. That was …. problematic for me.

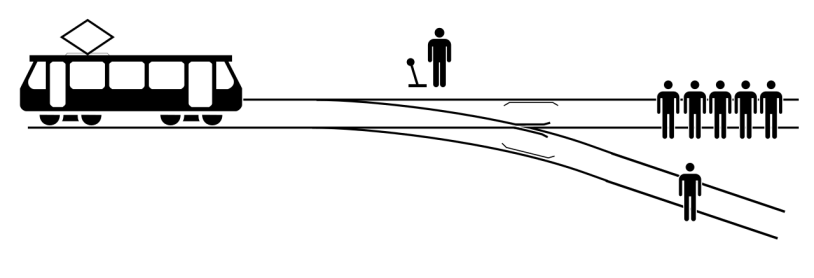

I am interested in your choice to use the trolley problem as this post’s image. In my mind, it points out that Jesus could work a miracle and save all the people tied to the tracks. And we mortals can’t. Like, we are completely unable to follow Jesus’s example. So now what? We have to sit with it, and release the expectation to *really* be like Jesus and find something more realistic to do.

Janey, wow! Just, wow!

Janey, just wonderful and personal thoughts. Thank you.

There are a few verses in the latter end of Luke 2 that never get much attention, namely 46-47 “After three days they found him in the temple courts, sitting among the teachers, listening to them and asking them questions. 47 Everyone who heard him was amazed at his understanding and his answers. Jesus listening, asking questions, and giving profound answers. I have heard much about the Jewish tradition approaching scripture in the spirit of debate, using them as a way to start a conversation, while western Christianity uses them to end the discussion. At 53 years old now, I’m not sure I know many things for certain, and like Dr Rangan Chatterjee frequently says–50% of what we say we know today with certainty will be proven wrong within 10 years, the problem is, we don’t know which 50%. In other words, whatever I write today is likely fundamentally inaccurate, or at least incomplete, but I sure enjoy coming here where the spirit of thought and debate is alive.

As far as the trolley problem, I know it’s normally used for situational ethics conversations. I like your idea. Mine was quite simple, “dilemmas”, this one being how to reconcile the human following the superhuman.

As for your final question, whether to release the expectation to “really” be like Jesus. I find Jesus almost unbearably compelling. He’s radical—showing us ways of living and being that feel beyond our reach. And his death, to me, reveals that humanity, at its core, still struggles to believe in a world governed by grace and mercy.

As I wrote in the post, “The gospel writers actually give us another picture. They show a Jesus who eats, grows, learns, gets tired, feels fear, weeps with friends, and prays for strength. In other words: someone real. Someone human. His life isn’t impressive because he was superhuman—it’s impressive because he was fully alive within human limits.”

That’s what draws me in. I’m compelled by a Jesus who descended into our humanity—who became fully human and therefore approachable, not distant. I can follow him not because he solved some abstract metaphysical problem, but because he showed us how to confront and heal real human problems.

To Andrews final question, what then is my (our) excuse for not living up to my potential?

I want to circle back to Janey’s moving example of her son’s perfectness. He was never anything but complete—yet so much of what we’re taught convinces us that we are not. We forget, or we’re indoctrinated into feeling “imperfect,” and then we imagine Jesus is training us to become something we’re fundamentally incapable of being. But really, he’s trying to wake us up to what we already are.

As others have noted, the idea of “perfection” is either a terrible mistranslation or a convenient interpretation that serves institutional priorities: order and control. At this point, calling “perfect” a moral issue would almost be a relief, compared to what it’s actually become—an instrument aimed at enforcing obedience and deference to authority.

If we embrace the original meaning of wholeness and completion, then we have to ask: When has someone or something reached its point of completion? Is an oak tree ever not an oak tree? Is a sapling just poking out of the ground somehow less “complete” than the full-grown tree? And if it isn’t complete, then when does it become so? What if a storm destroys that tiny oak before it matures—was it robbed of its chance to become “perfect,” through no fault of its own?

Applied to humans, this logic becomes even more troubling. In the way the LDS plan of salvation is often framed, the safest outcome would be to be born and then die the next day. (Didn’t Renlund even joke—badly—along these lines?) The longer we live, the more precarious the whole “worthiness” project becomes.

But if we start from the idea of original wholeness—of being complete at every stage, like the oak—then the whole conversation shifts. Instead of striving for some impossible ideal, we’re simply learning to live into who we already are.

Todd,

i understand that the following answer could be construed in all sorts of -phobic and -ist ways (e.g., ableist, homo- or transphobic), but:

I’d return your reference of Jesus’s early time in the temple courts with a scripture relating to Jesus’s later time in the temple courts…Mark 11:12-25 discusses quite infamously how Jesus comes upon a fig tree that had leaves but bore no fruit, then curses the fig tree so it withers and dies.

So, uhh, yeah, it’s possible for a tree to not complete its purpose (e.g., if it does not do “tree things” like produce fruit). And parabolically, this is absolutely supposed to be understood in context of the money changers in the temple court. That was not the purpose for which the temple courts were designed either. But it just seems like however you interpret it, there are ways of acting and behaving that do not fulfill human purpose. It’s not just about “living into who we already are” because if we go astray, then we can develop off track.

As i have said in comments to some of your other posts, while I like your way of thinking, I just feel it’s too “nice” to deal with a world with actual, perilous, disastrous choices. When “left to my own devices,” I don’t just naturally and effortlessly do good and awesome things unceasingly…no, I also have flaws, issues, shortcomings. and IDK, I don’t feel like I’m alone in thinking this. This almost laissez faire approach of “just live into who we already are” misses the fact that a lot of us have aspects of ourselves that do need to be reformed out.

i agree that i don’t think obedience to some rules promulgated by the institutional LDS church seems to be the right way to address this, but i also don’t think “be who you already are” is, either.

Thankyou Todd S.

I like your comment even better than your OP. You provoked an interesting discussion!

I strongly agree that no one can actually be certain about what we think we know. Reza Aslan agrees that Jesus of Nazareth is much more interesting than the Christ mythos that developed much later. I recently read Aslan’s “Zealot”, and am working on “God, a human history”. Both well-written and fascinating!

Andrew S.,

IMO, not only are we made whole through the Savior’s atonement–we are also made complete by joining with him.

What is more important, obtaining an understanding of and living dogma/doctrine, or obtaining an understanding of and living charity?

For me, the whole purpose of a Christian or a Latter-day Saint life is faith, hope, and charity. God himself came to earth and lived fully as a man. Wow!

When we return to the New Testament in our Come Follow Me series, I wish we would read and discuss the stories in Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. There is power in the stories. I don’t really like our focus on doctrine, but I wish we would read the stories instead. The stories paint the picture of the Jesus we are asked to follow.

There is a place for doctrine, but charity is more important.

“So, uhh, yeah, it’s possible for a tree to not complete its purpose (e.g., if it does not do “tree things” like produce fruit).”

Some trees are planted to produce fruit and if they don’t, then a fruit farmer will do the needful.

Where I live, we don’t care if our trees produce fruit. My SoCal suburb wants trees for shade and cooling in a warming earth, for aesthetics and as an offset to the carbon footprint of a human-created concrete jungle. Could the fig tree not be allowed to exist for other reasons?

If we agree that trees can be enough in diverse ways, can we extend this same grace to humans?

To the OP: Emulating Jesus seems tough even on my best days. I mean, I have to work to live. Jesus could simply borrow a few food scraps to feed himself. I spend significant time investing in raising four humans. Jesus escaped this burden. I have money problems. Jesus could conjure coins from fish. I have health issues that impact my daily life. Jesus did not. I have to plan for retirement. Jesus could simply consider the lilies. So while I think there are aspects of his teachings and life worth fighting for, becoming like him seems like an exercise in futility. There are too many dissimilarities in our lived experiences. Seems a better fit to consider the best traits from a multitude of humans in light of our own burdens and doing our best from there.

Chadwick, you bring up good points about following Jesus. But instead of being an itinerant preacher, you can be honest, kind, virtuous, forgiving, slow to condemn, and charitable. You can turn the other cheek. You can do good to those around you. You can edify others. You can live the gospel in your own life. You can emulate Jesus by making his teachings part of how you live your life. Emulating Jesus does not mean becoming an itinerant preacher. The question is, I think, can you emulate Jesus in your personal life while spending significant time investing in and raising four humans. You do not need to emulate Jesus by conjuring up coins in a fish’s mouth. You can plan for retirement, assiduously, and you should, but you can also from time to time consider the lilies. I do not think that living the life that Jesus taught in the New Testament (see ji’s post) is an exercise in futility.

Andrew — I’ve been thinking a lot about your comment. It’s one of the reasons I enjoy coming here. Every metaphor has its limits, and mine is certainly no exception.

Suzuki Roshi once told a group of his students, “Each of you is perfect just the way you are, and each of you can use a little improvement.” That paradox feels like the heart of transformation. I completely agree with you about flaws, poor decisions, selfish impulses, and even outright maliciousness. Jesus himself talks about trees that produce bad fruit or no fruit at all. I think my writing leans heavily toward the side of grace—maybe too far at times—and the pendulum swings away from the very real, perilous choices people make. I’m not speaking from abstraction there; my own life has had to reckon with choices that brought real harm to real people.

When it comes to the “barren fig tree,” which seems to point toward the religious elite whose righteousness never rose above personal worthiness, my question these days is less that they produce bad fruit and more why they do. Human behavior never emerges in a vacuum. Understanding those roots doesn’t absolve anyone of responsibility, but it does offer context. The lack of fruit has everything to do with a root problem—some distortion buried deep in belief or identity.

Humans are complicated, but also strangely simple. I honestly think 99% of us want the same basic things: to be valued, seen, understood, and loved. Ironically, those very desires often drive our most indecent behaviors as we try, in misguided ways, to extract affection and belonging.

So, are we “just living into who we already are”?

Maybe this is partly a matter of wording. Maybe it’s just a poetic way of describing a deeper process. But in many ways, I still stand by the premise, and I always come back to my favorite parable—the Prodigal Son. The text says, “He came to himself.” He made disastrous choices and squandered everything, but those choices eventually revealed their own fruitlessness. They triggered a remembering—a returning to who he always was. He strayed, he returned, and most importantly, his Father met him with an embrace instead of a stop sign.

Change is inevitable—maybe even certain—but what interests me is what actually produces lasting change. Why do I behave poorly? Why do I react the way I do? Why do some people grow into abusers or sources of mayhem? These questions matter deeply, and so does the hope of whether people like that—people like me—can be restored, or whether some are forever beyond redemption.

Todd S,

I don’t think your posts lean too far on grace. I think you could go further.

Overall, I think the problem with Pelagianism is that it gives the impression that we could just work on ourselves and better ourselves and that’s all that is needed.

This is “nice”. But I just don’t think that it accounts for the full story.

Paul write about wanting to do good, but being unable to. He does not the good that he wants to do, but the evil that he does not. It’s compulsive; it’s a fundamental break.

This is why the idea of “grace” is radical. It’s not something we earn. It’s not something we deserve. “Salvation” is saving us from ourselves, from compulsions we can’t just choose to deny on our own accord.

I agree the right messaging is that people can be restored. But as long as the implications is that it’s just a matter of a person reaching into themselves, rather than being *saved by something more powerful than they are*, then it’s not enough grace.

(Ok, again, I’m a nonbeliever, so I’m just cosplaying here. I don’t actually think there’s anything out there that can save us. But I do find that idea more hopeful. But if I were to seriously consider Christianity, it would be to give up and give in, not try to be master of everything.)

“Ok, again, I’m a nonbeliever, so I’m just cosplaying here.”

You’re very good at it–I appreciate your insights.

“But if I were to seriously consider Christianity, it would be to give up and give in, not try to be master of everything.”

While I do believe that we must be proactive in our discipleship in order to “go the distance” as we follow the Savior–ultimately each one of us at some point must come to terms with the reality of God’s love for his children. And that’s why I’m a near universalist; I’m of the opinion that the vast majority of individuals will not be able to resist his love forever. So if there’s a “giving in” as you say–in the end that’s what it amounts to IMO: not resisting God’s love for us.

How Torah common law interprets the writings of the NT Apostle Paul as akin to the writing of “Natan the prophet” who promoted the Shabbetai Zevi (1626–1676) false messiah abomination.

We Jews study the writings of the Apostle Paul, as that of an Agent Provocateur. A spy sent by Rabban Gamliel to infiltrate the Xtian movement; the story of his trip to Damascus encounter with God JeZeus, Acts 9:4, in the Heavens above story, permitted his entrance into the ranks of the Xtian movement as a Jewish spy.

Outside of Judea no Sanhedrin court has any legal jurisdiction to try a criminal case of Capital Crime and impose the death sentence. A 3-Man Torts court likewise does not have any jurisdiction to judge a Capital Crimes case of avoda zara, any more than does the story of stoning of individuals throwing stones as told in the story of the first church martyr Stephen.

Torah establishes 4 types of death penalties, stoning the most severe type due to the destruction of the human body. This most sever type of death penalty requires pushing off a prisoner, stripped naked from atop a 3 tower, something like a public hanging in America during the 19th Century. This tower about 19 feet tall.

The prisoner pushed off this execution tower onto a huge jagged rock below. The Talmud instructs that no person ever survived the impact of that fall; which caused the body to shatter into separate parts. Yet Paul’s “stoning” miraculously permitted Paul to get up by his own strength and walk away!

Once he reached Damascus, he preached the notion of faith in JeZeus, despite the Torah commandment which commands faith as: justice justice pursue. An later publicly preached that the mitzva of brit melah/circumcision had ceased to exist as a valid Torah commandment.

This theology rejected by Torah common judicial law. He further peached that Goyim themselves, not under the law. But his rhetoric propaganda failed to emphasize the day and night difference between Jewish judicial common law from Roman Caesar and Senate statute law. Just as it likewise failed to discern that “graphed on Goyim” metaphor, invalidates the Torah law which states that if any Goy perspective convert rejects even one Torah commandment, such a Goy – invalid as a valid convert to the Jewish faith.

Paul’s preaches that Goyim can be part of the Xtian community without fully adhering to Jewish law, including circumcision or dietary laws etc. This point is made crystal clear during the Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15), where the apostles and other church leaders discuss the requirements for Goyim conversion to this new God belief system.

While some Jewish leaders reject Paul’s message, others accept it. The division over Paul’s teachings does lead to controversies and challenges, but it’s not solely about rejecting circumcision. The purpose of this pointed rhetoric propaganda achieved the desired result of “Divide and conquer” among the Jewish people themselves.

At the same time Paul’s theology reflects any heresy theological debates within the early church which so define post NT church history. Paul’s clear-cut rejection of Torah commands altogether, not limited to brit melah and Kashrut which defines permitted and forbidden foods which Jews can and cannot eat.

Paul’s theology compares to Jewish spies sent to promote Civil War in the Syrian Greek empire which the lighting of the lights of Chanukka permanently remembers. Yechuda Maccabee functioned as a “spy”. As the leader of the Maccabee revolt against both the assimilated house of Aaron/Tzeddukim\ servants, tasked by the Syrian king with the duty to make Judea into the Syrian ‘banana republic’; modeled after the Persians who first built the Temple under Cyrus the Great. The construction of the 2nd Temple established the Tzeddukim as the loyal 2% of the Jewish population tasked with the kapo-Jewish obligation to extract the wealth of this conquered Judean province and transfer its wealth to Persepolis, the Capital of the Persian empire.

Hence the Persian empire the first empire to “convert” a restored Judea as a banana republic; Cyrus the first Persian king who employed Tzeddukim priests to achieve this critical “empire” task. Much like and comparable to how Centuries later Muhammad’s Koran conveniently rejected the consumption of pork, but permited Arabs and Muslims to consume camel flesh. Despite the Torah priority which prohibits camel prior to the prohibition of pork!

Clearly main stream Xtianity fails to this day to grasps the hostile qualities of Paul’s propaganda aimed to promote a Roman Civil War prior to the outbreak of the first great Jewish revolt in 66ce. Paul traveled to Rome and publicly preached/injected a theology of Xtian monotheism into a polytheistic Roman society which worshipped Caesar as “the son of God”.

Hence, Paul’s ‘miraculous’ survival from a Roman style stone completely forbidden by Torah common law, adds an intriguing layer to his Roman propaganda narrative, used to underscore his Roman mission to explode Civil War in Rome like as happened in Damascus about 1 Century earlier, and to declare this ‘divine endorsement’ as the Will of JeZeus as God.

Paul’s views on dietary laws and the later teachings in the Koran about permissible foods demonstrates how religious interpretations can evolve and adapt across cultures and times. This observation sheds light on the ongoing dialogue about legitimacy in religious commands. Please accept my open invitation for you to make a deeper exploration of the NT which you love and believe. Starting with why the gospel stories precede the writings of Paul despite the fact that Paul’s writings penned before the earliest gospel of Mark – written in both in Greek – not Hebrew or Aramaic – and in the city of Rome itself.

Also please explore the possibilities that Paul no more a prophet than Muhammad. Why? Because the Torah defines prophets as the police to enforce Sanhedrin court rulings. The Xtian literal reading of an exceptionally complex texts recorded through the letters of Paul compares to the Genesis Xtian overly simplistic literal reading of their genesis creation story whereby their believers declare that God created the Universe in Six Days and totally ignores the Torah opening introduction of “Torah wisdom commandments” commonly referred throughout the Talmud as “time-oriented commandments”. A Torah prophet commands mussar. Because mussar applies straight across the board to all generations of the chosen Cohen people. Torah prophets starting with Moshe and concluding with the prophet Yonah sent to foreign lands to first and foremost cause Israel to remember the oath brit sworn to the Avot that they and only they would father the chosen Cohen people. Hence the narrative of the JeZeus false messiah does not and cannot replace this Torah oath brit with the NT supersessionism replacement theology which defines the entire NT and OT rhetoric propaganda.

The gospel story which injects Greek mythology by which Zeus impregnates the mother of Hercules through the wolf dressed in sheep clothing – virgin birth inception through the “Holy Spirit”, which utterly and completely changes this Torah concept of Oral Torah middot Spirits revealed to Moshe Rabbeinu after the Golden Calf on mount Sinai as the further clarification of the revelation of the Holy Spirits revelation first expressed in the opening Sinai commandment. No word translation, as expressed by the mixed multitude assimilated and intermarried Israelites who confused a word translation אלהים as equal to the Holy Spirit 13 tohor middot first revealed at Horev/Sinai which the Talmud acknowledges as the Oral Torah which the church throughout its entire history has rejects like the Jews have rejected the false messiah JeZeus.

Torah common law simply not a religious personal belief system like the NT propaganda proclaims as its “Good News”. Torah establishes the faith of common law courts and not belief in any theologically created God. Why? Simply because the subject of Gods exists beyond the power and limits of the Human mind to grasp and understand. Church theology which calls their Nicene Trinity a mystery assumes that man can perceive understanding of the Divine. Just as the Torah revelation changes the Torah perspective which in the first book of creation perceives Divine Names as heavenly in origin to living within the Yatzir Ha-Tov hearts of the Cohen people alone — simply because only the 12 Tribes of Israel accept the revelation of the Torah to this very day. The NT and Koran never once convey the 1st Commandment Holy Spirit revelation of the Name. But rather both texts embrace the Golden Calf word translation avoda zarah.

This Torah Sinai revelation, which establishes the 2nd Sinai commandment, utterly rejects the theological foreign idea of Monotheism – regardless whether dressed up as Nicene Creed or Muslim Tawhid. The much later Mormon belief system, how much more so likewise and equally rejected as the meaning and k’vanna of the revelation of the Torah at Sinai.