Author Update: It turns out the idea I explain in this post has already been implemented. In 2011, the Affordable Care Act imposed a rule that required insurers to spend at least 80-85% of premium revenue on actual medical care. The hope was that this requirement would rein in runaway profits. It did not. And in fact, the spending requirement may have actually led to the ever-increasing insurance premiums that I was hoping to solve. From an article titled The ACA Rule That Accidentally Made Higher Healthcare Costs Profitable:

When the Affordable Care Act introduced the Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) rule in 2011, lawmakers believed they’d solved a fundamental problem with health insurance: runaway profits. The rule required insurers to spend at least 80-85% of premium revenue on actual medical care, capping their administrative costs and profits at 15-20%.

But fourteen years later, as Americans face sharp premium increases in 2026 and enhanced ACA subsidies expire, a closer look at the MLR rule reveals an unintended consequence: the very mechanism designed to control costs may be rewarding insurers when healthcare spending rises.

You know what? It was a good idea. Unfortunately, profit-hungry fiends found a way to gouge ordinary Americans in spite of the attempt to limit the obscenely high profits of the health insurance industry.

This post has four sections and I encourage you to think about which one you specifically disagree with rather than throwing out the whole post as soon as you find a sentence you dislike:

- The Problem is the Profit Motive

- Removing (or Limiting) the Profit Motive from Healthcare

- Enforcement

- FAQ

The Problem is the Profit Motive

Free market competition is supposed to bring down prices and improve products. That doesn’t work in healthcare because (1) the barriers to entry are so high and (2) the market isn’t very free.

The Barriers to Entry are High. Average people cannot found their own health insurance company or build their own hospitals. Right now, healthcare is in the hands of a rigid industry — both health insurance and providing health care. Competition isn’t really competitive because it’s so hard to gain a toehold in the industry.

The Market Isn’t Very Free. In general, it’s hard to shop around for health insurance. If you work, you’re limited to the plans your employer offers. Whether you have employer healthcare or buy it in the marketplace, you’re limited to what you can afford. You can’t change health insurance once you realize that your current insurer doesn’t cover the treatment the doctor says you need, but another health insurance company does. Changing health insurance is a lot harder than changing brands of toothpaste.

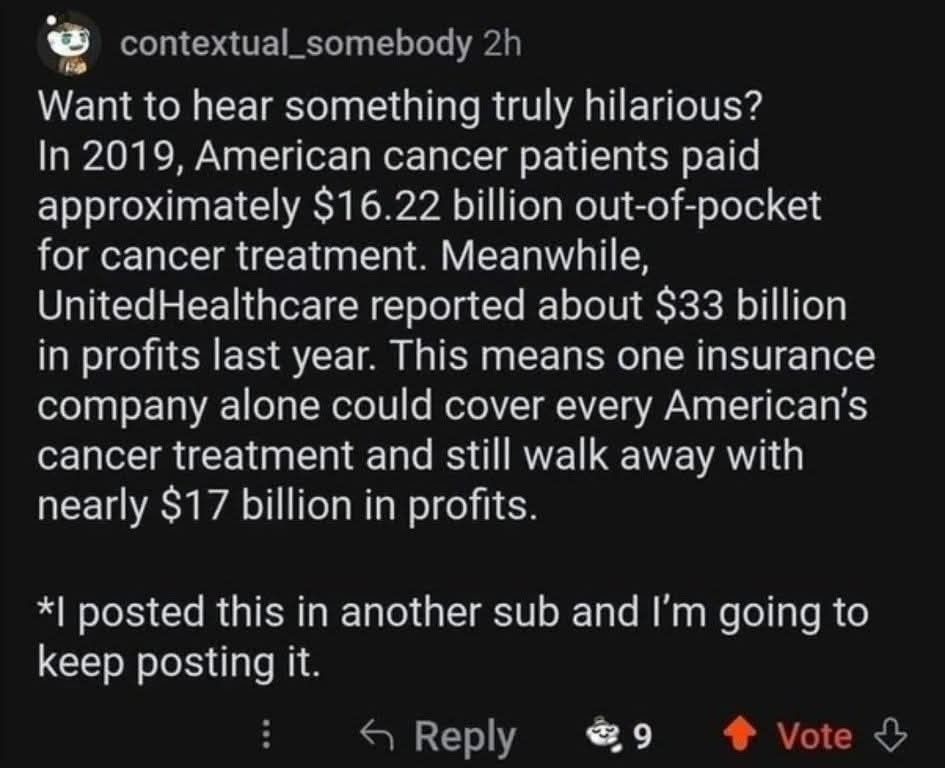

Health insurance companies generate profits when they collect more premiums than they pay out in claims. They have an incentive to deny claims because they can pocket that money. Those premium payments are then diverted into the pockets of people who are already rich. Health insurance CEOs earn salaries of $30 million and up. The seven largest publicly traded U.S. health insurance companies reported a combined $71.3 billion in profits for 2024. The health insurance company sends part of your premiums to their investors through dividends and stock buybacks in the tens of millions of dollars [source]. The company’s goal is not a reasonable return on investment for shareholders; instead the goal is to achieve higher profits every year, which means either premiums go up every year, or more claims are denied every year.

Denying and delaying claims is an art form among health insurance companies. For example, I’m currently in the fourth month of trying to get dental insurance to pay for my son’s wisdom teeth removal. The first time the oral surgeon’s office submitted the claim, they only paid for two teeth. The second time, they did something else nonsensical. They’re using AI to deny and delay payment for claims. The oral surgeon has to employ people full-time in a billing department to wrangle with insurance companies.

Agreement Checkpoint One (1). Before we move on, are you with me so far? Do you agree or disagree that the profit motive in healthcare is out of control and causes many, if not most, of the current problems with healthcare? Obviously, there are other problem issues, but check with yourself and see if you agree that the profit motive is a big issue.

Removing (or Limiting) the Profit Motive

If we can remove or limit the profit motive, we can keep the basic structure of USA health insurance intact. Private health insurance paid through your employer stays, and so do all the existing health insurance companies. Medicare and Medicaid stay, and don’t have to be expanded further. The Affordable Care Act marketplace stays so people who can’t get insurance through their job can buy policies through the marketplace. The existing procedures remain in place: you pay premiums, your doctor’s office submits the claim to the insurance company, your insurance company pays the claim.

How to Remove (or Limit) the Profit Motive

How do we do remove or limit the profit motive?

Congress adds a new paragraph to the income tax laws that covers the healthcare industry. The new paragraph would be added to 26 U.S.C. Section 832, which defines taxable income for health insurance companies. (Technically, Section 832 is for any insurance company that is not a life insurance company, and that includes health insurance companies.)

And before you get triggered because I said “tax law”, please let me assure you that what I’m proposing is possible. I used to be a tax lawyer. Tax law is drafted by tax lawyers (then Congress votes to make it law); the Treasury Regulations that explain tax law are written by tax lawyers; the IRS is staffed by tax lawyers; when a taxpayer company finds a tax lawyer who tells them how to exploit a loophole, other tax lawyers can close the loophole by writing legislation for Congress to pass (sometimes they don’t); if a taxpayer company commits tax fraud, there are tax lawyers and specialized forensic tax accountants who work for the government (the IRS) entirely to sniff out tax fraud and prosecute it. There are people who specialize in stuff like this and they’re used to working from suggestions. You tell a tax lawyer, “this is what I want to do” and the tax lawyer dives in and figures out the details. This is possible.

This doesn’t change individual income tax law at all. Your tax payments and returns don’t change.

The new paragraph would make the following change: A health insurance company must pay out in claims at least 90% of what it collects in premiums. If it pays out less than that, then whatever the insurance company kept is taxed at 100% and those funds are earmarked for Medicare and Medicaid.

Example: HealthCo collects $1,000,000 in premiums from individuals and employers. It pays out $750,000 in claims. Oops! That’s less than 90% of the premiums; it only paid 75% out in claims. So HealthCo has to pay tax of $150,000 (the 15% of premiums it didn’t pay out in claims) and all of that goes to Medicare and Medicaid.

Does HealthCo want to pay $150,000 in taxes? No, it does not. So instead, it makes sure that it pays out 90% of the premiums to claims. They’ll either pay more claims (yay!) or reduce the premiums they charge (also yay!). Poof! That’s the magic wand. Health insurance companies no longer want to make “recordbreaking profits.”

Agreement Checkpoint Two (2). Do you believe that tax lawyers could figure out a way to write a tax law that removes the profit motive from health insurance by limiting the profit to 10% of collected premiums?

Enforcement

People tend to be cynical about taxes and assume that everyone cheats and no one pays what they really owe. Something I learned as a tax lawyer is that it’s a lot harder for a business to cheat on its taxes than you think it is. And a huge business, like a health insurance company, has an even harder time because the IRS is looming over their shoulder constantly. Some companies are so big they are under a continuous audit. Seriously, the company has to provide an on-site office for the IRS agent and the IRS agent parks himself at the company and reviews accounting and banking records. The IRS agent knows as much about the company as the CFO (Chief Financial Officer) and the entire accounting department.

Obviously, you have to have enough IRS agents to handle the workload. This was one thing Joe Biden tried to do — the Inflation Reduction Act passed in 2022 provided a whole bunch of money to the IRS. The goal was to use that money to hire the multitude of tax lawyers necessary to audit the rich companies and the richest people. The Republicans successfully scared the public into believing that the hiring spree at the IRS was about picking on individuals who earned less than $250,000 per year. The Republicans clawed back a lot of that money from the IRS and then fired a whole bunch more employees. The IRS would need enough money to pay salaries for these specialized employees.

Agreement Checkpoint Three (3). Do you believe that the government could enforce this new tax law on health insurance companies?

FAQ

This section is about some nitty-gritty details and replying to some possible concerns and counter-arguments.

1. Why aren’t you limiting CEO salaries? Response: Limiting the profit motive should automatically bring CEO pay down to rational levels. Shareholders authorize stupidly high salaries because the CEO is giving them so much in profits. Once the profit motive is limited to 10%, the salary of CEOs will naturally come way down.

2. Will anyone be willing to work as a CEO for a health insurance company for a salary of only $650,000 instead of $30,000,000? Response: Yes. Idealists exist. I promise there are Americans who want health insurance to be fair and workable, and who will be willing to earn an annual salary of less than $1 million to do a job they believe in. The grifter CEOs can go find another industry to exploit.

3. What about the health insurance company’s operating expenses? Besides paying out claims, a health insurance company has to pay claims adjusters, rent an office, set up a computer system, and act like a business. Does that come out of health insurance premiums? Response: Yes, with limits. Obviously, we don’t want health insurance companies claiming they need golden toilets in their office building. Fortunately, these limits are already in place for some insurance companies (26 U.S.C. Section 833) and can be readily adapted to health insurance companies.

4. What about the crazy prices of prescription drugs? Response: Prescription drug prices are their own problem. This post is about one solution to one problem. Hopefully, the ripple effect of addressing outrageous health insurance company profits will have some impact on prescription drug prices. Health insurance companies will have more incentive to pay for prescription drugs since that counts as paying a claim. If prescription drug prices remain at price-gouging, recordbreaking, price points, then we take action aimed at overcharging for prescription drugs.

5. Won’t hospitals just inflate the claims they bill? This won’t necessarily bring down health care costs. Response: It’s possible that hospitals will try to grab more money. My thought is to solve one problem and see what the impact is on hospital billing. If hospital profits need to be limited too, we can address that after we see what the situation actually is.

6. This is too complicated! Health insurance companies can’t adapt to new rules! Response: Most laws phase in over time. With a three to five year phase-in period, health insurance companies will do just fine. Their accounting departments already know how much they collect in premiums, what their business operating expenses are, and how much they pay out in claims.

7. The stock market will crash when all the health insurance shareholders try to sell at once. Response: That’s another reason for a multi-year phase-in. The great sell-off of health insurance stock will be spread over a few years. The grifter shareholders who want to pocket your healthcare premiums will move on to invest in other industries. Regular investors will step in and the price of health insurance company stock will stabilize at a lower valuation. My 401(k) earns about 8% annually. Investment portfolios full of retirement accounts and mutual funds offered to regular humans will happily invest for a 10% return.

8. What about a reserve account? If a health insurance company has to pay out 90% every year, they won’t be able to afford claims if we have another pandemic and health care claims skyrocket! Response: The insurance income tax laws are already structured to allow reserve accounts.

9. If this would be so simple, why haven’t we already done it? Response: I’m suggesting the government use tax laws to limit the profits of a big industry. Republicans are already upset at that idea. Democrats who suggest taxing the super-rich lose elections. Health insurance lobbyists will fight dirty to stop this change. Tax bills have to originate in the House of Representatives. So passing something like this would require massive political effort, Democratic control of Congress, and somehow convincing voters that taxing the super-rich and funding the IRS is a good thing to do.

Conclusion

Insurance income tax is already its own section of the Tax Code. Health insurance companies already have accounting departments who know the dollar amounts involved. Health insurance companies already know how to file their own complicated income tax returns. The IRS already has agents trained to continuously audit big companies. This wouldn’t actually be that complicated to put into place.

While I don’t have anything against socialized medicine morally, I know a lot of Americans do. I believe that limiting the profit motive in the health insurance industry would solve a lot of healthcare problems, and also allow America to keep its current structure with private health insurance companies provided mostly through employers. This idea doesn’t require adding people to Medicare or Medicaid, nor would it replace the health insurance marketplace established by the Affordable Care Act. The USA keeps what it has. The change is that health insurance companies pay claims rather than gouging policyholders in order to make rich people richer.

For the discussion, pick one of the agreement checkpoints in the essay and discuss.

You have put some thought into this, and I appreciate the analysis — I also appreciate a good-faith attempt to have an honest conversation.

I am not an economist or attorney so I cannot comment on technical aspects of the proposal, but the proposal sounds reasonable to me. Using tax policy seems to make sense. If in negotiations the 90% figure ends up at 85%, well, that’s part of the process.

This post is off the subject of the mormon church, so I will drag it back. I was born in an LDS hospital. Yup, supported by the church as a semi charity. The cost was like $45, for a three day stay. Then when I was 6 months old, my mother was badly burned and hospitalized. Because she was still breast feeding, the hospital accommodated both of us and I stayed with her for the week she was hospitalized. That was another LDS sponsored hospital in Wyoming. That cost was about $80. Considering inflation since then, the costs would be about $4,500 for the birth and about $8,000 for the burn treatment.

But under for prophet hospitals, the cost of an uncomplicated birth, with a hospital stay reduced to just overnight, rather than the three days, is $45,000. I don’t have any guestament of a hospital stay of a full week for two people, but I am sure it would be over $80k. So, the for prophet thing has raised hospital cost by 10 times.

This estimate is comparable to the difference between socialized medicine and our for profit system. It s about 10 times more expensive.

Another example of the cost difference between socialized medicine and our greedy for prophet system is seen in our cost of drugs. I was getting one of my medications from Canada because my insurance would not cover it. So, while Canadians get their medicine for free, I am not a Canadian, so my cost was $30 per month. But my local pharmacy charges $300 per month. That is again about 10 themes as much.

I think not for prophet insurance co-ops, sort of like the difference between my credit union and for profit banks is a better option. Big companies could start these, just like big companies have started credit unions. Or worker’s unions could start them, just like workers unions used to before the unions were rendered powerless by the government being run by big business. Churches could start such insurance companies just like they used to sponsor hospitals before all the private hospitals were bought out by big business.

And we have come full circle. The for profit motive has taken over all our hospitals and all our insurance companies. Big business, oligarchs, run our current world. They buy our politicians with campaign contributions, so the government is not going to pass your suggested tax law, even if it might be a good idea. Oligarchs own our news stations and slant the news against workers unions, against the common people and toward what benefits the big companies that the oligarchs own. So, politicians who represent the people don’t even get voted in and you have voters voting against what is best for them. Because voters believe the slanted news. They you have your social media with conspiracy theories about how Democrats run child sex abuse rings and why are all the crazy conspiracy theories slanted against those evil Democratic socialists?

Why are you even starting this post with the assumption that we don’t want, gasp, socialized medicine?

Nope, we do want socialized medicine. Ask yourself, why do so many doctors want socialized medicine when it would actually cut their prophet?

We can’t go back in time to when religious groups ran hospitals as just part of taking care of people. Nope, religious groups have become for profit too. Look at the billions the Mormon church has. Look at the mega churches. They run on a profit motive.

We need socialized medicine.

I noticed that I used “prophet” when I ment “profit.” I guess I get used to writing “prophet” here and was in auto pilot. And our church is led by profit, not by a prophet.

I’ve always thought nonprofit companies should be running healthcare if they model is to be sustained. Several of our prominent general authorities made their financial gains by working for large health insurance companies such as United. In my opinion insurance companies with shareholders have no incentive to run a lean operation in behalf of their patients. Take the profit away from the corporations when dealing with people’s lives.

We need to start a club of LDS (or LDS orbit, lol) bloggers in tax (or in tax orbit). We can have you, Sam Brunson, and I’ll accept junior emeritus status lol (do former tax accountant count?) 😉

I think this is a fine proposal so far as it goes, but I think there are other factors that address high costs in health care. I’m thinking at a more basic level here…

My main issue is that I don’t think free markets are actually “supposed to bring down prices”. I think that free markets just suppose that

1. Individuals act according to rational self interest

2. Prices adjust according to supply and demand

3. Voluntary exchange should make allocations efficient.

With health, I feel like the problem is people are extremely demand inelastic. No matter what the price is, good health is usually just going to be something people pay for.

But even more, when health is jeopardized, people don’t have the luxury of comparison shopping. I agree with everything you wrote about there being barriers to entry, information asymmetry, high switch costs, etc, but even if these things were available, individuals are not in a good position to make informed thoughtful choices about whether they need procedure x or y, whether doctor a is better than doctor b, etc.

I’m not an expert at any of this, but it feels like there needs to be a role for “care navigator” for groups who know what the right procedures would be, what the right cost would be, and who advocate on behalf of the patient. It seems that a big issue is we do not structurally/formally have a role like this.

Insurance companies are NOT this (they are not denying claims to protect the patient…) Doctors and primary care physicians within hospitals also aren’t really this (they have the medical knowledge but aren’t really about managing patient economics and/or are beholden to the hospital).

Again, I could be saying something really dumb or ignorant here, but that would actually reinforce my point: this is not something individuals have the knowledge to navigate “rationally” on their own.

Your proposal of forcing insurance companies to pay 90% of premiums out in benefits is *chef’s kiss.* A business making more than 10-15% in profit margin is doing some shady business. I am going to be sharing this idea far and wide. Best thing I’ve ever heard.

I’ve previously documented some of the absolute nonsense I’ve been subject to during my own healthcare journey, such as being overcharged consistently, given completely fabricated reasons why, doing my own research (using their records they provided) and showing them why they are wrong, finally getting credits, but in the meantime being told to either fork over $5K today or cancel my radiation treatment because they said my deductible reset (a total lie) when I discovered that no, they were 3 months behind on billing and hadn’t even given me the insured rate. The incompetence is only rivalled by the lack of actually giving a damn what they are doing to people. That was just one example, but every single time I interacted with the healthcare system in 2024 (and there were unfortunately many times), the appointment or procedure was billed wrong–never in my favor–and I had to fight tooth and nail to get it back.

When Obamacare passed in 2012 I considered it the worst piece of legislation of my lifetime (born in 1965). I had the perspective of a right-winger/libertarian who fears government involvement. And so it probably goes without saying that back then my worst fear was Canadian-style national healthcare or the British National Health Service.

But I have to admit that I’ve changed my mind. I have four adult kids aged 22-31 who all make very nice livings in Law, Accounting, Finance, etc. And the one fear all four have is that they will have some kind of healthcare crisis that devastates them financially EVEN THOUGH THEY ALL HAVE HEALTH INSURANCE. And I think to myself, what about all the folks out there who don’t enjoy the benefits my family has? (side note: I was shocked at the response of my kids’ generation when United Healthcare CEO was shot dead in the streets of NYC).

I’m ready to trade in my capitalism credentials on this issue. Let’s see if the richest country in the world can do what every EU country does: provide a virtual guarantee of healthcare to its citizens. Will that require more taxes? Yes. Do I think most citizens of the United States would pay for guaranteed access? Yes.

Is health care taking care of the widows and orphans, or is that welfare? Either way, when insurance companies and medical institutions are so “rich” and pricing the average person out of getting care, I wonder.

We also call ourselves a “Christian Nation,” yet we don’t act Christian when it comes to either health care or welfare. It could be the profit model, or it could be the corruption in the government protecting both industries. It could also be the constant consolidation of companies and the limiting of services where it’s not profitable to operate, usually in rural or inner-city areas. Finally, there are the extreme salaries paid the CEOs and top corporate officials and the gap between them and the line workers, like nurses and even doctors. Thirty million compared to $50 an hour or a couple of hundred thousand a year is still a big gap.

So by talking about service and wealth, I’m bringing it back to the gospel. We have a system that feeds the rich and starves the poor of food or health care. I also find it interesting that the whole talk of “socialized medicine” came from arguments against universal health care that Truman tried to put forward in his administration. The rest of the world seemed to get it, but the US medical and insurance industries fought it with all their might. The result is that our healthcare costs more as a percentage of GNP than any other nation. In fact, if you took our tax rate and added healthcare costs, we are paying more than these socialized medicine countries are paying in taxes that support healthcare. They also have a lot of other benefits from public transportation to housing that the taxes are used for. They get better bang for their buck, but the super wealthy don’t get as much money, which sucks for them.

The irony of all this is that these socialist/secular countries act more Christian than our own “Christian Nation.”

So to me it’s not really a “socialized healthcare” discussion but a religious discussion of how do we meet the needs, as a society, to the least of our own, the widows and orphans. I believe we’d be much better off dealing with the problems of providing universal healthcare than we are now trying to fix a system that’s based on greed and exclusion. Yes, I’ll acknowledge the USA has the best healthcare in the world for some, but it also has the worst healthcare system in the world for many others. I’ll also ask what the difference is in not getting healthcare and having to wait to get served, as so many people say happens in socialized medicine, and having to wait for an in-network doctor because of insurance companies. If we looked at healthcare as a right, like speech, religion, or even owning guns, we could fix the problems; instead, it’s just how we do business.

I love the idea and think it’s worth a try. I have a daughter with birth defects and more than her share of challenges. I’ve have seen the incompetence and greed and don’t think I’ve ever been more angry than when they rejected a claim for my 2 year old daughter… that said I will throw out a few challenges / questions for the sake of discussion, but I’m decidedly not a fan of insurance companies.

Would this proposal effectively be placing a ceiling on insurance prices? Maybe that’s the entire point, but an economist might say price ceilings create other problems like scarcity, lower quality, and black markets. Idk, maybe we’d have to increase the number of medical professionals. Maybe not a bad thing but would have to be planned for.

Would insurance companies take advantage of reduced incentives for cost control? If their expenses rose then their prices would have “permission” to rise. Maybe the tax accountants and tax lawyers could figure that out, but it seems like a challenge. Our own LDS leaders don’t earn a salary but they sure do live like kings.

Might profit limits cause industry consolidation? Can you imagine two enormous insurance companies instead of a dozen? Compliance costs would rise, favoring large corporations. Smaller companies might have difficulty keeping up with new technology or innovating.

Interested in responses to these questions.

Janey this is brilliant. At the very least, it beats concepts of a plan or telling Americans to go negotiate their own subsidies.

Can I invite myself to the tax blog? I’m a CPA (but not a lawyer) with 20 years experience in corporate tax at EY. My CV is available upon request =)

I think Andrew S’s comments are mostly correct in how he is thinking about this. Some of the items he describes are touched on by Dr. Elizabeth Rosenthal’s book “The Price We Pay: What Broke American Health Care–and How to Fix It”.

Having said that, I think fundamentally the premise is wrong: the problem isn’t the profit motive. Yes, it’s part of the problem, but it’s far from the only problem. I would add a caveat: unregulated profit is part of the problem. But again, it’s far from the only problem. Solutions that focus on regulating the profit motive alone are going to come up short. We have to have a pro-supply policy, both in terms of medical providers and drug availability. And that needs to be coupled with smart, strong, and sensible regulation.

If you dig into the root causes of high healthcare US costs you will start to uncover that lack of strong regulation is also part of the problem. But also the US is very unhealthy and we chronic disease is costly to treat.

On the supply front: the AMA has restricted the amount of residencies, which restricts the number of providers and pushes up US physician salaries. We also have a cap on the number foreign doctors who can practice in the US. If we had more competition in allowing foreign drugs AND doctors to come into the US, that would put downward pressure by creating more supply. The current administration is actually doing some laudable things on this by aligning US drug prices with the lowest prices paid in other developed countries. Ironically it was always the democratic position to allow Medicare to negotiate drug prices in an attempt to regulate profits. Trump loves acting unilaterally and in this case he is using tariffs to try to negotiate down drug prices for drugs produced overseas. And while this admin is wrong on almost everything else, the instict to exert regulation on price and demand that US consumers pay what Germans, French, or the Spaniards pay for prescription drugs is largely correct.

My take is still focus on supply. Greatly increase the pipeline of providers. Allow PAs and NPs to take on more roles. Enact more transparency on pricing of everything: devices, drugs, procedures, etc. Use regulation where informational asymetries exist or the consumer is not equiped to evaluate the effectiveness or advisability of a treatment/procedure. Repeal most of the Bush-era Medicare expansion which did very little to bend the cost curve.

I like the proposal and I would vote for it. However, while I think it would improve things, but I’m less convinced that the consequences would be far reaching, just some fraction better than now. I’m not sure what fraction of revenue is currently going to claims, but suppose it’s 70% and we get it to 90%. So there are fewer claim denials, but do they go away entirely? I’ve heard it pointed out that the US system is merely outsourcing to the private sector the rationing of healthcare that must be done by government funded systems elsewhere. I think I agree with that idea, and while I don’t like a lot of things I see happening in the system now, I’m not sure that merely increasing the fraction of revenue that goes to fund care necessarily makes that rationing disappear. Maybe the most egregious examples go away. That would be a win.

I would support a Medicare for all system. If that is politically infeasible, here are some other things that I’d like to see happen:

1. decouple health insurance from employment by removing the tax deductibility of employer-sponsored plans, thus encouraging employers to stop providing it directly and sending everyone into the ACA markets. If employers want to provide some cash to help pay for it, that’s fine, but it would be good for everyone on employer sponsored plans to actually see how much they cost, and it would be good for the labor market if people can switch jobs easily and stay on the same insurance plan.

2. enforce some kind of rule that a patient gets one and only one bill for visiting a healthcare facility. In the last decade we’ve got these insane arrangements where everyone you interact with at a hospital is working for a different independent contractor that’s probably owned by some shadowy private equity company, and you never know whether you’ve fully paid all the bills or there’s another one coming. If all those separate entities are forced to agree among themselves on their share of a single bill sent to you, probably private equity pulls out because the big money opportunities disappear.

The ACA and state insurance regulations already impose profit caps on insurance companies. The consequence of such caps is the insurance companies argue for higher premiums! Higher premiums and even with a profit ratio cap the business makes more profits.

How do insurance companies justify higher premiums? By arguing that the cost of the thing insured is more expensive. Auto insurance premiums go higher as the cost to repair cars goes higher, and the technology added to cars makes cars more expensive to repair! Likewise for health care, insurers add coverage for new treatments and this increases the cost of health care and this means higher premiums!

What is missing from the insurance business is the incentive to lower costs! Until that incentive exists, the health care customer will continue to be shafted by ever higher prices.

By the way, another consequence of ACA and health insurance regulations is the health industry is financially rewarded for increasing its bureaucracy. Most new employment is health care. Not doctors or nurses. But rather persons who “manage healthcare”.

There is one law that already exists that would radically improve consumer power. It is that medical providers post prices and provide the same price to all customers. This law already exists and the Federal Government ignores it and allows insurance companies to conspire with healthcare providers to hide prices and deny customers a means to understand what it is they are paying for.

Andrew and Chadwick — starting a new blog for economic posting would be so much fun! I’m over-committed as it is right now, so I can’t take the lead on that. Instead, I just sneak in a post on W&T every so often that (as Anna noted) doesn’t have anything to do with church. But then, my LDS connection is saved by Instereo and Anna pointing out that healthcare is a moral issue. Sure, this is economics, but it’s a religious and moral issue as well. Jesus spent a lot of his earthly ministry healing people. Healthcare is a moral issue and it should attract more religious sermons on the topic of making sure everyone can get healthcare.

ji – correct. I’m throwing out numbers but, if this idea ever did catch the interest of a politician, the numbers would be negotiated.

Anna, I’m not opposed to socialized medicine myself. This is a compromise that I hope would appeal to people who don’t trust the idea of socialized medicine. Although, I also hope there are plenty of people like josh h, who have seen just how bad our system is. I’ve got a work friend who insists the USA’s system is superior to Canada’s because he knows a Canadian who had to wait 6 months to get his hip replaced. Stories about people who were bankrupted by a medical emergency, or who didn’t go to the dr at all due to the cost, don’t seem to sway him. *shrug*

Hawgrrl — thanks! And yeah, interacting with health insurance on a regular basis is enough to make anyone crazy. My oral surgeon’s office has three full-time employees just to deal with insurance idiocy. Plus all the calls and time put in by the patients. Single payer healthcare would streamline that process. Giving health insurance companies an incentive to pay out claims instead of deny them and hope people get sick of fighting the denial would also reduce the complexity of getting a claim paid. Or at least, that is my fond hope.

Trevor – I will take a stab at your questions later this evening.

Andrew – you bring up some good issues. They’re beyond the scope of the post. But yes, individual decisions about healthcare are a tricky area if you’ve got an unusual health condition. For someone like me, who doesn’t have chronic illness or anything unusual, my decisions are pretty straightforward.

Jacob L – sure, profit motive isn’t the ONLY problem. But it’s one that we can address by adding about two pages to the tax laws. Why not make the easy fix and see if ripple effects do anything? I don’t think the number of AMA residencies has much impact on the $71 billion in profits that health insurance companies took from our premiums.

I’ll start with the caveats: Heath insurance scares me and I hate dealing with it. I don’t work in any healthcare related fields. I also have no tax experience other than filling out basic tax forms each year. I’m not a lawyer, and I’m not an accountant. I am a humble math nerd googling things while eating lunch.

Not only is Janey’s plan good, but we already have it! The Affordable Care Act includes a provision that is known as the 80/20 rule, or the Medical Loss Ratio (MLR). (Google away to see if you can learn more than I have.) In short, 80% of premiums are required to go to claims, and insurance companies can be forced to refund premiums if they don’t meet the 80%. The other 20% is left for overhead expenses such as marketing, profits, salaries, administrative costs, and agent commissions. Obviously this is not the 90% suggested by Janey, but it does probably speak to what the Obama administration thought was obtainable in the political climate of 2011. But I don’t think this was meant to be a discussion of what is politically possible.

The higher the percentage goes, the more insurers are like poker dealers in Vegas; they get a fixed cut of every deal and therefore it is in their interest that prices go as high as possible. Perhaps there is a number somewhere between 80% and 99% where the system will be improved and operate better.

I googled “US insurance profit caps” and received the response:

“There is no single profit cap for US insurance companies, but the Affordable Care Act (ACA) limits how much can be kept from premiums. The ACA requires that insurers spend at least 80% of premiums on medical care for small and individual markets (or 85% for large employers), effectively capping the remaining 15-20% for administrative costs and profit. If an insurer spends less than this amount on medical care, it must rebate the difference to policyholders.”

I don’t believe changing the cap ratio is the fix.

What is missing from the US health insurance economy is consumer choice. ACA was explicit about stripping consumers of choice when it mandated Americans purchase health insurance and dictated what policies had to cover.

Choice is also eliminated by pushing consumers to purchase healthcare through an insurance policy, rather than purchasing it directly. This has the impact of making consumers unaware of the price being charged.

Observe how crazy it would be to apply the health insurance business model to other areas of the economy. If you bought groceries via insurance you would have no idea what items cost. You would invariably be charged much more than you should for whatever you did purchase.

A step in the right direction is to have all medical costs paid by the consumer, with the insurance policy reimbursing the customer. This would make consumers aware of prices and invite healthcare providers to compete on price. Currently, there is no competition and consumers get charged whatever they politically will bear.

Curious about your thoughts on how this would be an improvement over the already existing 80/20 rule from ACA.

@Disciple curious on how you think it will suddenly become possible for a regular family in the US to pay for, for example, cancer treatments which can easily go in to the millions of dollars. Even if your theory that price transparency works out and generates more straightforward competition bringing down the prices by, say, a very optimistic 50%… I still can’t afford that, can you?

Our best path forward really seems to be to get over our ourselves and do single payer healthcare, as all other developed nations have done. We already recognize that some functions of society work best when they are publicly funded (military, police, the courts, highway systems, etc) it’s time to add healthcare to the list.

Germany is usually considered a developed nation, but does it have single-payer healthcare? I could be wrong, but I read somewhere that Germany does not have a single-payer healthcare system. Instead, it uses insurance companies (not one with a nationwide monopoly). I am not saying that there health care is or is not better than ours, but the statement posted above that all other developed nations have single-payer healthcare might not be exactly right.

@Janey Capped AMA residencies is in fact a huge issue that is massively inflating healthcare costs. In 1997, we spent about 13.2% of GDP on health; by 2023, we spent 17.6%. 5.4% of current GDP is $1.46 trillion. $71 billion in profits is less than 5% of this increase in US healthcare costs. There is just no way that focusing on profits will bend the cost curve. It’s more of a distraction than a solution. It’s tantamount to thinking that rent control will make housing more affordable. We need more supply.

The Policy Mistake from 1997 That’s Driving Up Healthcare Costs

https://www.therebuild.pub/p/the-policy-mistake-from-1997-thats

What’s wrong with socialized medicine? I’ve lived in Canada for extended periods of probably the equivalent of 6 or 8 years. All of my family has used their nationalized health system. I’ve seen it work from maintenance well care to urgent life/death situations in my own household. It’s a completely different model than ours and I’m here to say it’s better.

Yes, I know people wait for some necessary procedures. Yes, I know people of means travel for immediate care. But the major reasons I can say with confidence that it’s superior are that 1) people who are out of work or disadvantaged for any number of reasons reasons are not without health care and they outrank the US on every metric of care, 2) because it mobilizes to protect public health on a dime while Covid demonstrated how inept our system is to public health emergencies and 3) because the people who are privileged and make health care policy have the same healthcare options, in general, that the rest of the population has.

The first time I returned to the US after having availed myself of BC provincial care I asked my doctor what his opinion of socialized medicine was. He surprised me by replying “best medical records in the world”.

@ A Disciple wrote: “How do insurance companies justify higher premiums? By arguing that the cost of the thing insured is more expensive.”

This is kind of a well-known phenomenon in the Intermountain system. They are ostensibly a “non-profit” system, but in order to reduce their profits they just keep building huge, massive new buildings. They also sponsored the Las Vegas Raiders. The way to reduce profits is just profligate spending, inflated bureaucracy, wasteful vanity projects. But none of this actually reduces the costs, nor does it actually improve care. In fact, the the frontline caregivers in the equation are often an afterthought. Monopoly and consolidation has had a deleterious effect in the US healthcare. Not only is there less competition, less transparency, fewer market choices, we also have weak/ineffective regulation. Even if we want taxpayer funded, free at the point of delivery healthcare, we still have to very much tackle cost.

A lot of your comments are spot on when it comes to transparency in pricing, consumer driven choice/availability. But pricing and competition does have its limits in healthcare since many issues are emergent. No one shops for the best prices on ER care when they are having a heart attack or stroke. We will always need strong governmental regulation to avoid potential abuses when forgoing care is not a realistic option.

As someone mentioned, Germany does not do single payer but instead mandates personal insurance going back to Bismarck’s day. That said, I do not know how Germany regulates insurance companies. It would be interesting to learn more. This is a good discussion.

Folks … DaveW and Disciple are right. My brilliant idea was already thought up by people a couple decades ago and put into the Affordable Care Act, with an 80% ratio instead of 90%.

This post shall forever be a reminder to me that I am not as smart as I think I am and I should not write posts based on one outrageous headline but should instead read generally about the topic I want to write about. I will go put on my sackcloth and sit in ashes.

(pause)

I’m back.

As ji pointed out, this is a good discussion. So what have I learned while googling from my pile of ashes? The Medical Loss Ratio (which is what they call the requirement to spend 80% of the premiums on paying out claims) has actually contributed to the rise in healthcare premiums. Health insurance companies get to keep 20% and 20% of $100 is a bigger number than 20% of $50.

Or, as healthaffairs.com put it: “The MLR requirement is well-intentioned, but its cost-plus design is flawed. By capping insurer overhead and profit margins without addressing the structural drivers of unaffordable health care, the requirement unintentionally incentivizes insurers to prioritize horizontal and vertical integration over cost containment and innovation. These dynamics compromise plan quality, reduce enrollees’ choices of affordable plans, and increase taxpayer burdens.” (https://www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/unintended-consequences-aca-s-medical-loss-ratio-requirement)

What the MLR has done is drive health insurance companies to vertically integrate healthcare. Jacob L summarized it well — insurance companies build huge and flashy hospitals and then they can “upcode” and charge more for services. All these expenditures meet the 80% MLR requirement. And premiums keep going up.

The solution may very well be busting up monopolies and prohibiting health insurance companies from owning the pharmacies and hospitals.

Disciple has a good point about healthcare providers being more transparent about the actual costs.

The Hospital Price Transparency Act took effect in 2021 and requires hospitals to post prices on their websites. I’ve read criticisms that the prices are hard to find. Just now, I got on the website for the closest hospital to see how long it took to find out what an MRI costs. There was a link to “pricing transparency” right on the first page, so that was encouraging. But then I started clicking around.

Every page said this: “A Hospital Standard Charges list is not a price list and should not be used to estimate patient payment. The information in a Hospital Standard Charges list does not constitute a quote nor a price guarantee for any service. The charge amounts in the Hospital Standard Charges list rarely reflect what you will be asked to pay for medical services and supplies on a final bill.”

In other words, the hospital isn’t going to tell us how much it costs to get an MRI. In order to get an estimate, I had to put in my insurance information. They’ll estimate what they will bill my insurance. Finding out the actual cost is something my hospital is dodging.

And forcing a statement of cost is vital. Charles pointed out that a lot of treatments for serious conditions, can be insanely expensive. I question if the expense is really necessary, or if health insurance companies inflate the costs. We’ve all heard a story, or experienced firsthand, when someone got billed $25 for one tablet of Tylenol. How much does an MRI actually cost? Take the cost of the MRI, amortize that over the number of years it should last, add in the annual salary of the MRI tech, a bit for general overhead and space in the hospital … a hospital should be able to determine what the actual cost it needs to cover to give someone an MRI.

It’s like if you took your car in for repairs and they wouldn’t tell you how much it would cost to change the brake pads until they knew how much money you made.

Charles,

Insurance only works when the expected rate of loss is very low. When there is a 1 in 1000 chance of a house suffering catastrophic damage then insurance can be priced and sold. When those odds increase tenfold then the insurance pricing becomes prohibitive – as has happened in coastal Florida and high fire risk areas of California.

A huge flaw in US health insurance is that the insurance vehicle is used to socialize the costs of expenses that are highly expected to occur! We expect kids to get a sore throat. We expect people to go to the doctor for a checkup. This confounding of expected and unexpected medical expenses greatly distorts the healthcare economy.

Consider, how much would an oil change for a car cost if oil changes were covered by insurance? Would it make any sense to cover oil changes with insurance? Oil changes are an expected maintenance cost of owning a car. You can’t insure for a thing you expect to happen! And yet US health insurance does this and the result is an economic distortion that greatly inflates costs and prices.

So about your cancer example. People ought to be able to purchase insurance for cancer treatment and the policy would be relatively affordable given having cancer is not an expected yearly expense.

And what about those who don’t purchase cancer insurance and get cancer? Do we allow people to live with the consequence of their choices?

The less we in society can tolerate people facing the consequence for their choices the more we must socialize the economy. And the more we socialize the economy the greater the economic distortions as the power of prices and personal self interest is lost.

Observe that in fully socialized healthcare access to cancer treatment is rationed by time, which in some cases results in delayed / failed treatment. Is that more or less cruel than denying treatment to those who personally chose not to be covered for it?

Part of why the hospital prices are hard to figure out is due to the fact that a lot of care is unpaid. Patients that cannot afford a copay or deductible or even insurance at all still access care through the emergency department. Due to federal law (EMTALA), the emergency department MUST provide a screening exam and thanks to malpractice suits, if a problem is found, the hospital is obligated to treat. The hospital will bill these people but they do not pay their bills so the hospital has to make up the difference somehow. They do this by overcharging the paying ie insured patients. So your hospital fee is subsidizing the care of someone else. If everyone could be counted on to pay their bill, charging the same price to everyone makes sense but it is unethical to not care for the suffering just because they cannot pay and it is also unethical to ask people to work for free.

National healthcare would ensure that all providers get paid for their services and all patients have access to care regardless of their financial circumstances. The industry absolutely needs to be regulated whether by managing insurance companies or creating a new system, this regulation would just systematize what is already happening.

Trevor – I’m going to take a stab at answering your questions now. And, (good news!) since what I’ve proposed has already been in place for a couple decades, there are answers to your questions!

Would this proposal effectively be placing a ceiling on insurance prices?

Answer: that was my hope, actually. But what actually happened was that insurance premiums went up so that the dollars the insurance company could keep would go up. Without some method for price controls, requiring a certain percentage of payout did not achieve the desired outcome.

Would insurance companies take advantage of reduced incentives for cost control? If their expenses rose then their prices would have “permission” to rise.

Answer: ding, ding, ding! You got it! That’s exactly what happened. Health insurance companies raised their expenses.

Might profit limits cause industry consolidation? Can you imagine two enormous insurance companies instead of a dozen?

Answer: That’s what happened. Health insurance companies consolidated into vertical monopolies. The insurance company owns the hospital and the pharmacy, and that way it can increase expenses as much as it wants in order to justify premiums going up. And up. And up.

Perhaps we update antitrust laws to break up this type of healthcare monopolies.

First off the cost/ person is just over half in countries with universal healthcare compared with the American system.

My doctor in Australia is not paid a wage by the government; he is a contractor. He is paid for performing a short or long medical examination or another procedure. The last time I went to my doctor it was to provide a medical certificate which I need to drive a car when I am over 75. The doctor can accept the government payment or add an extra co payment. The government is at present increasing the doctor payments so very rarely will there be more than the government payment.

I assume the American doctor is the same except he is paid by the patient or insurance company.

I understand 3/4 of American hospitals are not for profit. In Australia state governments own most of the public hospitals, and the federal government runs Medicare. So like the doctor they have an agreed price for a service. On top of this you can buy health insurance, and there is a private hospital system. I do not because I believe money should be in the public system.

The federal government has an incentive to keep people healthy so is regularly running campaigns against exposure to skin cancer, obesity, and awareness of other things like bowel cancer. They also look at anomalies, so if one doctor has higher rates of a particular procedure he might get a please explain. They can also look at hospitals that have higher rates of c sections for example.

The result is 5 years extra of life. Lower infant mortality rates and paying half as much for better healthcare.

It does look like the the problem with the American system is the insurance companies v the federal government in Australia. Whether you can regulate them as Janey suggests or just have to replace them? Perhaps Obama care would make them uncompetetive?

For medicine we have the PBS pharmaceutical benefits scheme. If a drug company wants to sell a drug in Aus it goes to the PBS, who examine the effectiveness, and the price, and decide whether to list it. For pensioners a prescription costs $6.60 but there is an annual limit. Because I had a stroke 20 months ago I am taking 7 different drugs a day. Three months ago I reached that limit so my drugs are free for the rest of the year. The pharmacist provides me with a blister pack that contains my daily medications for a month.

“I understand 3/4 of American hospitals are not for profit.”

I am not sure if this is true — but even if it is, the doctors at the hospitals are likely not hospital employees but are independent contractors or employees of a physician company. Many hospitals, profit and non-profit, have contracted out their emergency rooms to physician-owned corporations with a primary focus on revenue extraction, not patient care. A person visiting an emergency room at a hospital will get bills from the hospital, and very likely separate additional bills from one or more physicians, labs, and so forth.

The entire American health care system is focused on revenue extraction. The personalized care we sometimes see on TV doctor shows is largely fiction.

But even if a hospital is non-profit, people like Elder Cook (before his calling as an apostle) make millions on revenue extraction – that is the real purpose.

What’s interesting here is that a number of people have commented who are in political disagreement who all acknowledge that there is a healthcare problem in the US. Costs are too high. Individuals can get crushed by medical debt. The system is ripping people off and profiting from their worst moments. Something has to change. Honestly I don’t know what the answer is. But this post had some excellent thinking

Agree Brad. The failure of American healthcare is something about which we all can agree. The hitch is realizing agreement on the fix and one reason for this is there is no obvious solution, but only trade-offs.

As for “non-profits” the greatest “non-profit” is the US Government and yet everyone elected to office in that government becomes a multimillionaire.

There is nothing special about an institution being a “non-profit” and often the label hides tremendous greed by the institution insiders.

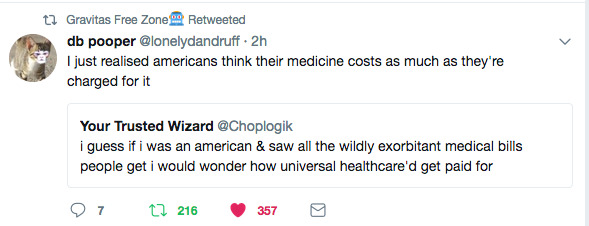

Geoff Aus — I always appreciate you sharing your perspective from Australia. I was vaguely aware that other countries aren’t as simple as I might think when I hear ‘socialized’ or ‘single payer.’ It sounds like Australian healthcare is shared among fed govt, state govt, and private health insurance. It’s still got a complex structure. But the fact that the cost is half … that text message I put in the original post is correct. Americans tend to think that healthcare costs what we pay for it, and that’s not true. Our costs are so inflated. If Australia can treat, say, a broken arm for $300 then why does someone in the USA need health insurance to pay out $900 and then pay another $200 for the deductible? (I’m making up dollar amounts, but the I think Disciple’s point about the lack of pricing transparency, combined with ji’s point about revenue extraction, makes Americans think that healthcare is much more expensive than it actually is.)

I tend to agree with ji that the purpose of American healthcare is revenue extraction. And the thing is, I don’t believe that’s why people study medicine. I bet a lot of doctors and nurses chose healthcare as a profession because they want to help people. I stubbornly believe there is a lot of idealism in medicine. But then the businessmen started emphasizing revenue extraction and they’ve been very successful at that.

As Brad D and Disciple note, people across the political spectrum can agree there is a problem. I hope we can find some bipartisan approaches to solutions. Nothing will be a simple fix, but even partial solutions could help. Now we know that forcing insurance companies to pay out at least 80% of the premiums they collect isn’t effective. What’s next? Breaking up vertical monopolies? Working with the AMA to increase residencies? Price limits on some routine procedures?

I see the German system has come up in the comments here. Long ago as a graduate student I spent a few months as a guest researcher at a German university. I was enrolled as a part-time employee of the university and into the German health insurance system. I don’t claim a deep knowledge of how it works, but I recall choosing one of several insurance providers when I did the paperwork. My paycheck had a deduction to pay for the insurance, which as I understood it was effectively a flat tax that scaled with my income, and was the same no matter which insurer I chose. I assume it was supplemented by state subsidies to the insurer. The insurance companies are not competing with each other not on price but on quality of service.

In many ways, the ACA system of regulated exchanges was more or less modeled on that German system. The difference is that the ACA system was only for people not getting employer sponsored coverage, so it’s a small minority of the market. I think the US system would benefit from simplification, which is why I’d like to see us get everyone into the ACA exchanges and decouple insurance from employment. That would get nearly everyone into a handful of large risk pools rather than the highly fragmented ones we have now, which would be good for insurers and customers alike. There’s plenty of room for debate about the appropriate level of government subsidies to make premiums affordable at the lower end of the income distribution, but I think the structure overall works. It works in Germany, and I believe they do something similar in Switzerland. We do need Republicans to get on board with mandatory insurance, which also exists in those countries. A person who foregoes insurance despite being able to afford it is contributing to a potential free rider problem, one catastrophic accident away from unaffordable bills that ultimately get spread over everyone else paying for the system.

So many good comments here, and really nuanced perspectives. One thing I’d like to point out—maybe obvious, but worth saying—is that U.S. healthcare quality is excellent if you have a lot of money. We absolutely have world-class doctors, procedures, and facilities. If you can pay, you can get phenomenal care. But we deliver that care at an extraordinarily high cost, which means the value for money is not great. And “socialized” or single-payer systems aren’t monolithic—some handle costs terribly, others bend the cost curve quite well by keeping pro-supply, pro-competition elements within a framework that treats healthcare as a universal right and public good.

Where the U.S. system really falls short is that we have neither strong market forces nor strong regulation. It’s the worst of both worlds for cost containment. The absence of real market discipline has allowed the healthcare machine—“revenue optimization” is a perfect term here—to become the central organizing principle. And that comes at the expense of both patients and providers.

As an RN, so much of my time was spent documenting every microscopic intervention. Charting wasn’t primarily about improving patient care across a team; it was about maximizing billing under ICD codes and creating a defensive record in case of malpractice. Burned-out nurses often got hired as chart-review specialists whose entire job was to comb through documentation looking for new ways to upcharge Medicare or Medicaid. The tacit goal of these positions was never efficiency, prevention, or better health outcomes. It was billing optimization, full stop.

One idea I’d love to see on the ACA exchange: insurers should have to disclose their claim-denial percentages in a clear, standardized way. A lot of the sympathy for Luigi Mangione (in the wake of the murder of that healthcare executive) stemmed from frustration over insurers using blanket denials—now increasingly automated, even AI-driven. Patients are forced to spend absurd amounts of time fighting to get basic procedures covered. The friction isn’t a bug; it’s a feature designed to shift costs back onto the patient.

Universal healthcare, Medicaid for all, single payer, socialized medicine, whatever you want to call it, is the only serious, long term solution to America’s healthcare horror show. I personally will never vote for a candidate again who doesn’t support this.

“Charting wasn’t primarily about improving patient care across a team; it was about maximizing billing under ICD codes and creating a defensive record in case of malpractice. Burned-out nurses often got hired as chart-review specialists whose entire job was to comb through documentation looking for new ways to upcharge Medicare or Medicaid. The tacit goal of these positions was never efficiency, prevention, or better health outcomes. It was billing optimization, full stop.”

I believe this is a truthful statement.