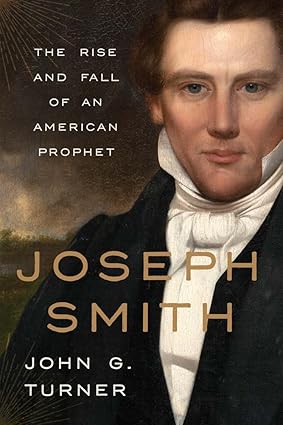

[Part One; Part Two] Let’s finish up discussion of the new Joseph Smith biography by John Turner, Joseph Smith: The Rise and Fall of an American Prophet (Yale Univ. Press, 2025). When the last major biography of Joseph Smith came out in 2005, Richard Bushman’s Rough Stone Rolling, it received sustained attention and discussion. Turner’s book certainly deserves attention and discussion, but I’m not seeing it. So this might be your last chance to talk about the book! There is a lot of material to talk about for the Nauvoo period, so my discussion will necessarily be selective. I’ll just blurb a few of the most interesting points from the book.

First, the big picture. The New York period, to early 1831, covers what you might call “foundational LDS history,” the stuff that always gets talked about in LDS talks and lessons: First Vision, Moroni, seer stones, Book of Mormon and its translation, angelic appearances and priesthood claims (the claims came later; the events are situated in the New York period). You’ve heard it all before. The Kirtland period is bifurcated into what happened in Kirtland (development of LDS doctrine you are familiar with, D&C 76 and the three kingdoms, D&C 93 and the Word of Wisdom, visions and keys, stakes and high councils, etc.) and what happened in Missouri (the failed quest for Zion). Kirtland-era doctrine is more or less the LDS doctrine of today. The Church of today is rooted in the events in New York and the doctrine of Kirtland.

The Nauvoo period is something different. Things got a little crazy in Nauvoo, and Joseph Smith himself sort of went out of orbit. Lots of esoteric doctrine, not just polygamy, much of which the modern LDS Church just wants to forget (remember, it tried that with polygamy). Escalating legal trouble for Joseph Smith, culminating in his death by assassination while in state custody. Eventually, the Saints were driven not just out of Nauvoo but out of the United States entirely. So much happened in Nauvoo that there are not one, not two, but at least three excellent books on that period alone, by Benjamin Park, Glen Leonard, and Robert Flanders. Check those out if you want the whole story.

“The Mormons … attracted hostility wherever they settled in large numbers” (p. 235). The initial hope was that Nauvoo would be different, but it wasn’t. Having the Nauvoo Charter, control of municipal courts, and a Nauvoo Legion to protect the Saints was Joseph’s plan to keep Nauvoo and the Saints safe this time around, and it worked for a while but not for long. The same story unfolded on a longer time scale in Utah through the end of the 19th century. This question is still relevant in 2025, when there is still a lot of animosity directed toward the Church and its members. Is it all just undeserved persecution, stirred up by evil forces or just natural religious bigotry, that hounds the Church and its members? Or is there something about the whole Mormon shtick, the Mormon way of life, that somehow generates this hostility? It’s something of a mystery how the Church and its members can generate both public praise (wholesome living, the Church welfare system, the MoTab Choir) and persistent public distrust and animosity.

Polygamy and all that. It really got going in Nauvoo and it is probably Nauvoo’s biggest legacy to the modern Church. But it is important to remember it was *secret* polygamy. Joseph was never faced with having to publicly acknowledge his practice (whatever it was) and his extension of it to a small group of close followers. Here are a couple of comments from Turner. “Joseph’s marriages also fit into a pattern of growing recklessness” (p. 235). Everyone loves a scandal, today as well as in the 1840s, and Joseph should have known that his reckless practice of plural marriage would create huge problems for not just himself but for the entire Church. “Joseph’s polygamy was a principle without a plan other than its rapid expansion” (p. 235). Modern LDS look to D&C 132 as some sort of controlling or definitive plan for polygamy, which is seriously misleading. It wasn’t published until 1852, so it likely had little influence on what happened in Nauvoo. The evolving and expanding practice drove the development of the doctrine. To even call it doctrine is misleading: there was a large variety of justifications and explanations offered for the practice. That’s still the case.

Again, all this is still relevant here in 2025. First, it’s worth remembering that until maybe thirty years ago, the Church successfully removed polygamy from its curriculum and historical discussions, so successfully that when the Internet burst onto the scene and average members of the Church inevitably stumbled upon an account of early LDS polygamy, many of them were shocked — shocked!! — to learn that Joseph practiced polygamy. It’s only recently that the Church has really had to deal with publicly explaining or defending polygamy, to its own membership more than to the public at large (who will never be persuaded). Second, and possibly related to the first point, is the recent emergence of “polygamy deniers” among the general membership. Finding none of the official explanations pleasing, many LDS now simply deny that Joseph, dear Joseph, could possibly have conducted polygamy activites (i.e., sex) with other women behind Emma’s back. Third, all of the “sister wives” series and documentaries. Polygamy is the scandal that will just never die for the Church.

Other stuff. There is the Egytptian mummies and scrolls episode, resulting in the Book of Abraham (again, controversy around the Book of Abraham is still with us almost two centuries later). There is the expansion of what became temple activities and ordinances, starting with baptism for the dead and then what became the endowment (expanding on earlier rituals first introduced in Kirtland). There was the Council of Fifty and the strange and abortive attempt to establish some sort of theocratic pseudo world government, above and beyond the public government of Nauvoo, a mixture of priesthood and kingship, that was largely forgotten until recent historical work, including access to the minutes of the Council of Fifty, drew attention to it. There was the proliferation of offices and councils, contributing to what we now call the Succession Crisis, with the apostles soon taking over leadership of the Church. All that and more if you read Turner’s book or dive deeper by reading one or all of the Nauvoo books mentioned earlier.

A peek at an alternate history. Winding things up, let’s consider the culminating event of the book, the death by assassination of Joseph and his brother Hyrum. Martyrs exercise an enormous emotional pull over followers. Joseph’s martyrdom seemed to cement the loyalty and dedication of Nauvoo Mormons to not just the memory of Joseph but to the Church as an institution as well. It powered them across the plains and the mountains into the Salt Lake Valley and beyond, re-establishing the LDS Church in the West and setting the stage for another wild chapter in LDS history. Read Turner’s biography of Brigham Young to get a big chunk of that story.

It is interesting to speculate what would have become of the Church had Joseph not died in Carthage. What if another round of dissent had split Nauvoo and eroded loyalty to Joseph? What if Joseph’s polygamy had become public knowledge and he had to face up to it? What if confidence in him had waned and large numbers of Nauvoo residents just gave up on the project and went their various ways? The Church might have withered away. It may very well be the case that the modern flourishing of the LDS Church was made possible only by Joseph suffering a martyr’s death at the relatively young age of 38.

And thus we have reached the end of the tale. Comments are welcome.

I read Turner’s book and compliment it for being a serious examination of Joseph Smith’s history. Turner is fair, if not extremely sympathetic of Joseph Smith. But it is the need for Turner to be sympathetic of Smith where the book leaves believers without answers. For what Turner relates of Joseph Smith is a man who is spiritually, financially and morally reckless.

The spiritual and financial escapades are one thing. The moral entanglements are another thing and the LDS church has no good answers for them. Turner takes witness claims of their “polygamy” experience with Joseph Smith at face value and this means he recognizes that Smith is having sexual relations with multiple women, some very young, some married, and lying about it. There is no way to explain or understand this behavior.

And so for believers, Turner’s book is a dead end. This is not Turner’s fault. The problem is the subject. For believers, the story of Joseph Smith only makes sense as a myth where the unacceptable aspects of Smith’s life are simply whitewashed. I personally like the mythical Joseph Smith! I don’t know what to do with the real thing.

I have read Kingdom of Nauvoo, an excellent read that shows in a responsible way, how things, especially JS went went off the rails.

I have also read the Nauvoo Expositor articles that caused JS to order the press destroyed, and led to his legal arrest and subsequent assassination (unlike the founding myth that portrays him as a martyr). I find it very interesting that the church now acknowledges the Expositor article on JS polygamy, to be a credible source of information, instead of anti-Mormon lies, as it has previously been labeled (latest GT Essay on polygamy).

I believe it is very unfortunate that JS was killed because it gave the church its martyr myth that fueled its establishment.

I think I was in the camp that wasn’t sure whether I needed to read Turner’s book, as I’ve already read Rough Stone Rolling multiple times. Given your posts here, though, I now think I really do need to read it.

I agree that Turner’s book isn’t receiving as much attention as Bushman’s. I think one reason for this is that Bushman’s book is still pretty recent, and people are still reading it for the first time and coming to terms with its contents., so Turner’s book may come “too soon” on the heels of Bushman’s work (even though Bushman’s book was published 20 years ago!). I think another reason is that a lot of people have been willing to read Bushman’s book because it was written by a well-respected, faithful Mormon insider. Turner is an outsider, so a lot of Church members will just assume he’s not going to be “fair” to Joseph.

It was interesting to read the OP’s take on the Nauvoo period because it exactly matches up with what I’ve felt about that time period for many, many years. In Nauvoo, Joseph seems to have just lost control and done a bunch of really crazy stuff. Some of this is stuff the Church accepts today. Much, but not all, of what it still accepts from Nauvoo is controversial and problematic for the Church. Certainly, the Church has also backed away from a lot of what Joseph did and taught in Nauvoo.

I’m doing a lot of agreeing with the OP here, but I have also wondered for many years what would have happened to the Church if Joseph hasn’t been killed. I do think there is a very real chance that Joseph’s recklessness would have eventually caused a lot of of division and dissent to the point where the whole movement may have just eventually fizzled out. I do occassionally hear or read a nuanced member talk about how they believe God may have allowed (or even had a hand in) Joseph to be killed in order to save the Church from all the stuff Joseph was doing (especially polygamy, but other things too). Where many orthodox members need Joseph to be a blameless (and, as noted, some even go so far as to need him to be monogamous with Emma despite the overwhelming evidence to the contrary) martyr prophet who “sealed his testimony with his blood” like other great prophets of the past, some nuanced members need Joseph to be a flawed prophet whose bad behavior and false teachings eventually led to his demise, but saved the Church he started, which, for them, was still worth saving.

Just another unfaithful husband.

OP: “Turner’s book certainly deserves attention and discussion, but I’m not seeing it.”

Are we in a post-Joseph Smith Papers release funk? Is Joseph’s life and times the Burned-Over District of Mormon history? I’ve almost bought this book a couple of times, but have held off, telling myself things like this: need to focus on Dickens (my reading goal this year); need to pinch pennies (my goal every year); just not feeling it this time (this year and maybe every year going forward).

I would read Turner’s book if I had time & money to spare. Dave B, beyond having been written by an outsider, would you say this book has any special selling point over previous efforts? Regardless, thank you for the write-up.

Jake,

Try your public library. Mine had the book. I don’t think it’s worth buying unless one has a keen interest in early church history and one likes to add books to their shelves.

His book was outstanding. Highly recommend.

Thanks for the comments, everyone.

Jake, I think A Disciple summarized the book well in his comment above. It is ” a serious examination of Joseph Smith’s history. Turner is fair, if not extremely sympathetic of Joseph Smith.” It avoids what one might call the rather free speculation of Brodie’s biography but is not so openly sympathetic, even supportive, of Joseph as Bushman is in Rough Stone Rolling. Yes, check your library or their ebook affiliates. I have saved myself a lot of money by using interlibrary loan and ebook options at the library.