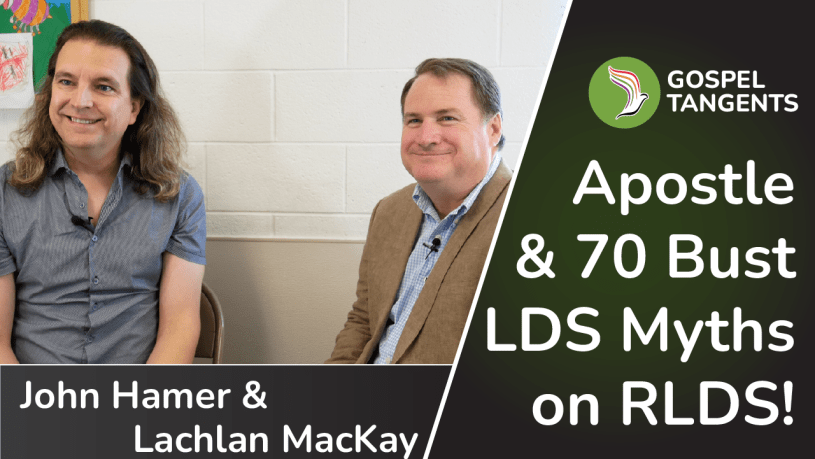

This is a rebroadcast of my 2018 interview with John Hamer & Lachlan MacKay from the Community of Christ. They’ll bust some LDS myths about the Kirtland Temple, Word of Wisdom, Alice Cooper, and more! Check it out!

A Journey Through Kirtland and Beyond

The early history of the Latter-day Saint movement is far richer and more complex than many realize, marked by vibrant architectural innovations, evolving theological understandings, and a dramatic succession crisis that led to the formation of numerous distinct traditions. Recent discussions with Community of Christ leaders, Apostle Lachlan MacKay and Seventy John Hamer, offer fascinating insights into this intricate past, shedding light on topics ranging from the Kirtland Temple‘s original appearance to the diverse interpretations of core doctrines.

John is the author of Scattering of the Saints: Schism Within Mormonism.

Bust LDS Myths on Kirtland Temple: Kaleidoscope of Early Worship

The Kirtland Temple, a pivotal edifice in early Latter-day Saint history, holds a storied past, not least because of its surprising original aesthetics and a tumultuous ownership saga. When first constructed, the building did not present the pristine white façade it does today. Rather, it was designed to emulate a grand, cut-stone look, achieved through an ingenious building technique introduced by Artemus Millet.

The walls, approximately two feet thick and 45 feet high, were constructed from rubble, primarily sandstone, held together with mortar. To create the desired elegant appearance, a hard plaster or stucco finish was immediately applied to the exterior. This stucco was mixed with crushed old crockery and glass, making the surface sparkle brilliantly when struck by sunlight. Mortar joints were then painted onto the walls, giving the illusion of large, meticulously cut stone blocks from a distance. Far from white, the temple was described as “blue” in the 1830s, likely a slate gray hue. Even the wooden shingles were dipped in red lead paint for preservation, and the front doors were olive green, presenting a far more colorful structure than we envision today. This vibrant exterior, sadly, was toned down over the years due to fading, extensive patching of cracks, rust streaks from iron in the sandstone, and eventually, the removal and replacement of stucco in the 1950s, leading to its brilliant white appearance only since the 1960s.

The temple’s initial function also differed significantly from modern Latter-day Saint temples. In Kirtland, it served as a public house for worship with a strong emphasis on spiritual and intellectual empowerment. Two-thirds of the temple was dedicated to classroom space, where people would attend worship on Sundays and school six days a week. It even housed the Kirtland High School, accommodating students from six years old through adulthood, making it the center of community life. This public access contrasted with the Nauvoo temple, where a tithe-payer’s receipt was required for the baptismal font, a precursor to the modern temple recommend concept.

The Kirtland Temple’s ownership history is equally complex, described as “a mess”. Joseph Smith sometimes owned it personally and at other times on behalf of the Church. Amid financial difficulties, it was signed over to William Marks to protect it from creditors. After Joseph Smith’s death, there were attempts by various groups, including Brigham Young’s followers, to sell or claim the temple. A particularly violent incident in 1838 saw dissenters storm the temple with guns and knives, aiming to take possession, only to be ejected by police amidst a chaotic scene involving a toppled stovepipe and soot. The Community of Christ’s “Kirtland temple suit” in the 1880s was primarily about establishing identity as Joseph Smith Jr.’s true church, rather than merely securing ownership, despite an initial favorable ruling being dismissed on procedural grounds.

Evolving Temple Worship and Theological Insights

The sources highlight significant differences in temple worship and theology between the Kirtland era and later developments in Nauvoo and beyond. Notably, the Kirtland Temple had no baptismal font, and endowment ceremonies as understood later were not taking place there.

The concept of baptism for the dead seems to have its origins in Nauvoo, though rooted in Joseph Smith’s earlier concern for his unbaptized brother, Alvin. The vision of Alvin in the celestial kingdom in 1836 (LDS D&C 137) brought relief, but the idea of baptism by proxy didn’t fully materialize until Nauvoo, with early baptisms even occurring in the Mississippi River before the temple font was ready. Other traditions, like James Strang’s, also adopted this practice. The Community of Christ initially found the idea appealing but, lacking a temple to practice it, it eventually ceased to be part of their tradition.

The vision of Elijah on April 3, 1836, in the Kirtland Temple, is interpreted differently by various Latter-day Saint traditions. For the Community of Christ, a key insight is that this vision of the Risen Lord occurred on Easter Sunday, emphasizing the Christ-centered nature of the event. Modern LDS tradition often anachronistically reads the vision as the moment the sealing power for plural marriage was restored. However, historical context suggests the early Saints, a “millennial sect,” were focused on end-times theology and Elijah’s return to “turn the hearts of the children to the fathers” in preparation for the literal Second Coming, not plural marriage. The vision of Alvin in D&C 137 is also clarified as being about preaching in the spirit prison, not baptism for the dead, a later reinterpretation.

Endowment ceremonies in Kirtland also evolved. Initially, “endowment with power from on high” meant gathering to be empowered by the Holy Spirit for missionary outreach. Over time, ordinances were added, including ordination to the Melchizedek Priesthood, feet washing, and a ritual cleansing with cinnamon whiskey and perfumed water. This purification ritual was performed just prior to entering the temple, followed by anointing with oil and sealing blessings on the third floor, a process that took weeks and was considered essential for missionaries going overseas.

Succession and Schisms: The Fragmented Heritage

Following Joseph Smith’s assassination in 1844, a profound succession crisis emerged, creating a vacuum that led to numerous leadership claims and the formation of diverse Latter-day Saint traditions. The death of Hyrum Smith alongside Joseph, who held an “anomalous role” as assistant president, left the question of succession open.

Sidney Rigdon, as the last surviving member of the First Presidency, held a strong canonical claim to leadership, supported by the church’s incorporation documents which stipulated succession through the First Presidency. However, he was outmaneuvered by Brigham Young, who, as president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, established the precedent of the senior apostle succeeding, a practice not found in early canon law but adopted to prevent Rigdon’s leadership. Rigdon subsequently attempted to reorganize the church in Pittsburgh, but his movement eventually atomized, leading to the formation of smaller groups like the Bickertonites.

Among the most influential rivals to Brigham Young was James Strang, a recent convert who rapidly gained a following. Strang claimed angelic ordination simultaneous with Joseph’s death and presented a contested letter purportedly appointing him as Joseph’s successor. He further bolstered his claims with new prophetic signs, including the translation of the “Voree plates,” physical artifacts seen by thousands, which foretold a refuge in Voree, Wisconsin, and the emergence of a great successor. Strang gathered followers, first in Voree and then on Beaver Island in Lake Michigan, where they built a thriving colony. His movement controversially adopted polygamy, which Strang claimed to discover through translating a separate set of “brass plates”. His opposition to selling whiskey to Native Americans also caused friction with neighbors. Strang was eventually martyred in 1856, and his followers were brutally dispersed, suffering severe persecution.

Other notable groups included:

- Lyman Wight’s followers (Wightites): Wight, a senior member of the Council of Fifty, believed he was called to relocate to Texas and formed a successful colony there. Most Wightites eventually joined the Reorganization.

- Alpheus Cutler’s followers (Cutlerites): Cutler, a mason of the Nauvoo Temple and a leader of the Council of Fifty, also believed Joseph Smith III would be the successor. His small group is known for maintaining a unique, longer, and secret Nauvoo-era endowment ceremony, making them a subject of great historical interest despite their dwindling numbers.

- Hedrickites: This group, also known as the Church of Christ, focused on redeeming Zion in Jackson County, Missouri, acquiring portions of the original Temple Lot. They reject the Doctrine and Covenants, citing changes from the original Book of Commandments.

The Community of Christ (historically RLDS Church) emerged from various scattered branches in the Midwest that were dissatisfied with the leadership of Brigham Young and James Strang. These branches, praying for guidance, coalesced around the idea of lineal succession, eventually inviting Joseph Smith III to become their prophet-president in 1860. This “Josephite tradition” drew many dissenters from other groups, including those who had gone west to Utah but were disillusioned.

Bust LDS Myths on Word of Wisdom

The Word of Wisdom, a key revelation in Mormonism, is another area where historical context significantly alters modern understanding. In the early 19th century, “strong drink” clearly referred to distilled spirits like whiskey and rum, not all alcohol. Wine, specifically redcurrant wine, was used for sacrament offerings, including at the Kirtland Temple dedication and even at Latter-day Saint weddings for wine and cake. “Mild barley drinks,” meaning beer, were considered “good for the body”.

Joseph Smith was a strong proponent of temperance, which at the time meant moderation, not prohibition. People were admonished for “overindulgence or drinking strong drink,” particularly those struggling with alcoholism, rather than for simply having a glass of beer. This historical understanding emphasizes avoiding addiction and promoting moderation, a principle still encouraged by the Community of Christ. Even practical uses of substances mentioned in the Word of Wisdom are noted, such as cinnamon whiskey for ritual cleansing prior to temple ordinances, and tobacco for poultices or to energize mules. The admonition to eat meat sparingly even led some to avoid meat between Easter and Thanksgiving. Understanding these contextual nuances reveals a much different daily practice and interpretation than often assumed today.

The rich tapestry of early Latter-day Saint history, as illuminated by these detailed discussions, reveals a period of dynamic evolution, diverse interpretations, and profound challenges that shaped a multitude of traditions. From the vibrant construction of the Kirtland Temple to the complex web of succession claims and evolving doctrines, this history offers a compelling narrative of faith, struggle, and the enduring quest for spiritual truth.

There was an article in the Salt Lake Tribune on Sunday, September 7, 2025, about rumors within the church related to celebrities and their involvement or non-involvement in the church. That article with this post leads me to think, 1—people’s need to create “inspirational” stories to justify their belief/faith, 2- their need to sanitize aspects of the past as per the color of the temple, and 3- their rewriting of history to justify the present, like the Word of Wisdom and total absence of any alcohol. It’s to the point where even the restored gospel has people calling for a restoration and using it to justify starting other churches, polygamous or otherwise.

The details on the Kirtland Temple are good. It’s like they built a temple, then tried to figure out what to do with it that was different from just a community church and meeting place. This is timely as well, with the LDS Come Follow Me lessons covering the Kirtland period and the Kirtland Temple this month.

Will we return the Word of Wisdom one day to what it was originally, a word of wise counsel? How many good people can’t go to the temple because of the WoW? (Rather, how many cannot go because of selective enforcement? We don’t keep people out because of eating too much meat.) Might they be strengthened if they could go? How many good people are effectively shunned by other members? As I understand it, and I might not understand correctly, beer and wine were not originally “covered” by the WoW, and there was much tolerance. Is WoW an area where we might be too much like the Pharisees? Is it what goes in or what comes out that pollutes the body? Maybe each of us could look first to the beam in our own eyes before focusing on the motes in other people’s eyes.

Kyle Beshears, a baptist pastor, said there was a growing protestant movement to shun wine (due to alcoholism which was a bigger problem in the 19th century) in favor of grape juice. It’s why Welch’s Grape Juice became a company. Mormons followed this trend.

Then when Utah voted to overturn Prohibition, Heber J Grant was ticked and made abstinence a temple recommend requirement.

Rick B, Heber J Grant was ticked off with the citizens of Utah (most of whom were members of the church) about their vote to get rid of Prohibition in 1933. If my source is right (Wikipedia), Heber J Grant made adherence to the Word of Wisdom a temple recommend matter in 1921. So while the sentiment is probably right, the chronology you propose might be a little off. Actually, Utah voted in 1919 to pass the Eighteenth Amendment, which made Prohibition the law of the land, on 16 January, the same day as North Carolina, Nebraska, Missouri, and Wyoming, and when those certificates arrived in the capital city the amendment was passed. So Pres. Grant’s response in making WoW a temple recommend question may been a continuation of the temperance movement, which was dominant in most states (including Utah) in 1919. All of that changed by 1933, not necessarily because people embraced alcohol, but because of the way governments at various levels enforced Prohibition, making criminals out of people who had been law-abiding citizens, and also helping organized crime become much stronger. Unintended consequences?

Grant doubled down on the Word of Wisdom as a temple standard following Prohibition’s repeal. Before 1933, local leaders winked at alcohol consumption. My own grandmother talked about alcohol being served at ward parties in the 1920’s.