Over the past few months, I’ve been thinking about the concept of “agency.” I am vaguely aware that LDS church leaders have changed what agency means in an LDS context, but when I was growing up, agency was used in the sense of “free will”.

I struggled with this. I could not force myself to believe in truth claims and just have faith. When I first heard about Calvinism and the concept of reprobation, I understood it intuitively. I named my personal blog Irresisitible (Dis)grace to play off the concept.

I’ve been thinking about “agency” because of a different community, though. Have you heard of TPOT (“That Part of Twitter”)? That’s a whole rabbit hole that I’m not going to get into, but I’ll give you a flavor of this community with a tweet series that popped up a few months back about their particular use of the term “agency”:

If you got lost by their idiosyncratic vocabulary [“energy + consciousness + radical permission (inverse learned helplessness)”? ] then let me put it in a different way:

High agency means that People Can Just Do Things.

Many people live with self-limiting beliefs like learned helplessness, a belief in external locus of control, a lack of belief in self-efficacy. They think that doing “things” (things can be anything) requires permission, adherence to rules, and chances are, you don’t have it and can’t get it.

But a person who shifts to high agency isn’t stopped by that. If they need permission, they’ll figure out how to get it. But it goes much further than that. If they are not given permission, they’ll go around it. People can just do things. They don’t need permission.

Let’s do a Rorschach test:

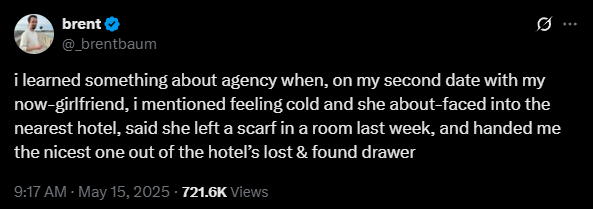

What is your reaction to this tweet?

The replies and quotes were quite polarized. Some people were aghast at the manipulation, the deception, the theft. While others thought it was resourceful and sweet. (There were those in the middle who rationalized it as contextual: is someone really going to be missing a scarf from a hotel’s lost & found drawer…?)

The answer that you have, in my mind, is a good encapsulation of whether you are high or low agency.

But I think this also captures its drawback. While I recognize that many people can benefit from the idea that “you can just do things,” I am scared of the high agency mentality. It reads to me as lawlessness, sociopathy. Even years before DOGE, I heard Elon Musk held as an exemplar of “high agency.” But now, whatever your view of Donald Trump and the rest of his presidential administration, it demonstrates high agency. There’s no need to wait for Congressional approval or to let court judicial review hold you back when you are highly agentic. You can just do things.

So, that also got me thinking back to the church, and I had a thought: in this definition, prophetic figures like Joseph Smith and Brigham Young absolutely were exemplars of high agency, and I think this is part and parcel of why these charismatic figures are polarizing.

We debate today about what the prophetic mantle involves. What standards should we expect from a prophet? How good should they be compared to the baseline person? How moral? Nuanced views of Joseph Smith want us to reconcile and accept that God can work with imperfect people. God must work through imperfect people.

But I have wondered if something else might be the case: prophets aren’t prophets in spite of their moral foibles, but because of them. Because the thing that allows them to create communities and institutions that last is precisely the same impetus to just do things regardless of convention or rules or morality.

In this sense, we can say that the subsequent “routinization of charisma” as documented by Max Weber precisely represents the constraint of high agency.

Have you seen the documentary series that released recently “An Inconvenient Faith”? That’s worth its own post, but there was podcast episode where some of the participants discussed the documentary series. And I’m thinking about a part of this podcast where John Dehlin shares his thoughts about what makes a prophet a prophet. At 1:12:29 (Yes, 1 hour is not even half way, sorry), John says:

Alright, here’s my point of view. I’m reading John Turner’s biography on Joseph Smith and I’m reading Fawn Brodie’s “No Man Knows My History,” and I’ve come to a conclusion: a prophet is not someone who teaches an eternal, unchanging truth; a prophet is not someone who speaks to God, a prophet is not someone who’s an upstanding moral character. A prophet is nothing more than someone who teaches a bunch of stuff that inspires people, that ends up creating a community of people that enjoy being together and have a great experience overall, and that endures multi-generational. And they’re gonna be super flawed; they’re gonna change what they teach; they’re gonna make all sorts of claims that aren’t true, but what makes them a prophet is they inspire people, it forms a community that endures…

…they do what’s really hard. They do something I’ve tried to do and failed multiple times: get a bunch of people to…support each other.

This point gets glossed over, rejected, or thrown out by the rest of the panel on the podcast — it’s obviously not what the LDS church claims a prophet is — but I think there’s something to this. While this doesn’t produce a particularly moral vision, or allow us to actually differentiate truth or any of the things we would like to get from religion (John openly accepts all competing claimed prophets as being prophets, no matter how odious, immoral, or amoral they are), it does produce something formidable that should not be easily dismissed. Even if we don’t like it, we have to reckon that whatever this is that drives these people can and will steamroll the world and its institutions if we are not careful.

- What are your thoughts on “high agency”?

- Do you recognize the danger or do you see it as something more neutral or positive?

- Do you think it is a good way to describe at least part of the appeal of early church leaders, and does it also help explain their misdeeds?

Very interesting discussion. Rule-breakers follow a risky strategy. If they succeed — not in breaking the rule(s), but in accomplishing some additional goal — maybe they generate continued support. But if they fail, there’s an easy explanation: they broke the rules, what did they expect? Some people break the rules more successfully than others.

And we do need to distinguish between breaking with tradition or standard practices, which might propel a business leader’s young company to wild success, and breaking regulations or laws, which is riskier and will invariably prompt conflict and possibly legal consequences.

How successful was Joseph the Rule-Breaker? He broke with Christian tradition to spell out a four-level heaven (three glories and an outer darkness). No big deal. He broke with tradition by gathering all converts into one location. Not illegal, but it quickly gave rise to local opposition everywhere it was practiced, sometimes violent opposition. When denied legislative approval to establish a bank, he flaunted the law by forming an anti-banking society in Kirtland and circulated the notes anyway — it was a disaster. He flaunted both tradition and the law by practicing plural marriage, and that too was a disaster. That’s a very mixed track record, with more examples on both sides of the ledger, of course.

Back a few, OK, a lot of years when Jim Jones ordered a massacre, my mother made a comment. It really hit me hard. I was still a believer, but knew my mother had issues with the church that she mostly refused to talk about. It was kind of an angry outburst even for her to reveal this much, but what she said has held up as a truth in all the research I have done. She said that Jim Jones wasn’t that much different than Joseph Smith. Later I found a book that talked about the personality of those who start cults. They didn’t exclude Joseph Smith in their “cult leaders” but he fit their description of the personality and weaknesses and psychological profile. As other cult leaders hit the news, I saw those same traits. Charismatic, yes, but with traits of narcissism or psychopathology. But they all had a kind of license to do and say what they wanted. They all had started kind of a sexual harem and usually part of the harem had girls.

Sexual abuse of girls was the downfall of Jim Jone’s cult and David Koresh’s cult and if you stop believing Brigham Young’s denials his sexual predation led to the death of Joseph Smith.

You can call it polygamy if you like but under polygamy the women actually live (at least for a while under later Mormon polygamy) with the husband and are openly married to him. Joseph Smith did not publicly acknowledge his sexual exploits as wives, but the sexual relationship was hidden like adultery would be. That isn’t polygamy. The point of marriage is to publicly recognize the relationship so that children will be recognized as that man’s children. That didn’t happen with Joseph Smith, so I really have trouble calling what he did polygamy. I don’t know what to call it other than deceiving women into thinking the sex was legit and he would publicly recognize children as his. But then he starts “marrying” women who are already married and still living with their husbands so the child would look like the other man’s child. There were even accusations that he had Dr Bennet doing abortions. That is not polygamy because he was not treating the women as “wives” but as mistresses. It was totally *her* problem if she got pregnant.

So, anyway, I agree with that quote from John Dehlin that a prophet isn’t someone who is more moral or even basically righteous with human weaknesses. Who gets followed as a prophet is someone who is charismatic, can pull people together under his leadership, get them to believe in him, and form a community. And it doesn’t even need to be a lasting community because Jim Jone’s followers “drank the koolaid” and other modern cults self destructed. Thanks to Joseph Smith for not taking his followers with him as so many other modern “prophets” did.

You could even look at Trump as a cult leader because his followers see him as chosen by God, maybe not as a prophet but as a leader whose going to fix the world, get rid of evil, and they really do not care about accusations or convictions that he is a sexual predator even of teen girls. One of Trump’s rape accusers was 13 at the time. People refuse to see his obvious lies because they want to believe. They refuse to see that he is a con man, not a brilliant businessman.

And rather than inventing a new word or a whole new concept for people who think they can do anything they want, maybe we should see this as an old idea that people are trying to pass off as a great new idea with a whole new vocabulary. Maybe we should just call it good old selfishness. There is a proper balance between the kind of person who walks into any motel and steals something from lost and found, (it would have been just as quick to go to a store and buy one) and the kind of person who suffers from learned helplessness. It is called healthy, rather than narcissistic or psychopath on the one hand and learned helplessness on the other. We do kind of lack terms for people who are too fearful or too caught up in religion to act on their own behalf. We do have the concept of learned helplessness for people who have life experiences that teach them there is nothing they are capable of to change their situation. See, a little selfishness is good and healthy, too much and you hurt others.

Andrews S.,

I appreciate the observations you share but I agree with Anna that we do not need to create a new word and mangle the meaning of an existing word.

“Agency” has a clear and significant meaning. First, consider the word “Agent” which means a person who is authorized to act on behalf of, and in the interest of, another person. An agent in the world of law and finance has specific legal rights and responsibilities. To be an agent onto oneself means one represents oneself and is accountable to oneself for actions taken. Agency concerns the ability to act for oneself or another person. Modifiers to the word may clarify the role of action, ie “Free Agency” in sports indicates a person can freely negotiate a contract with other teams. “Moral Agency” indicates a person has liberty to exercise moral discernment and is accountable for decisions made. It mangles the word Agency to assign a modifier that nullifies the word, as if a certain type of agency means one no longer has accountability for actions taken.

The X post you show is interesting. It seems to reflect persons who try to be interesting by incorrectly defining words. The word that is applicable to this scenario is “Conscientiousness”. People who have high conscientiousness feel it is important to act honorably and with high integrity. Scrupulous people self regulate their behavior. Unscrupulous persons do not hold this self regard. Rather, unscrupulous persons impose on others the burden to hold them accountable, with the expectation that they won’t be held accountable.

So I am curious and willing to learn. Why was the phrase “High agency” introduced when the word “Unscrupulous” and “Unprincipled” already exist?

Just wanted to share a couple of articles discussing “High Agency” from a positive/appreciative perspective. The main thing here is proponents of high agency wouldn’t think of describing it as being unscrupulous or unprincipled because they view it as a positive trait. In these articles, high agency is still associated with a sort of accountability — but it’s the sort of accountability that you see in high stakes startup and tech culture, where returns to investors matter the most (and externalities like pollution, inequality, etc., don’t matter as much as long as Line Goes Up).

https://www.forbes.com/sites/stephenmiles/2025/02/27/high-agency-leadership/

https://www.inc.com/jessica-stillman/high-agency-is-the-new-hot-business-buzzword-heres-why-some-psychologists-hate-it/91156370

A little while ago I came to the conclusion that I was living my life with “low agency”. I had a cult-member’s mentality and felt like my options were limited by what the church said was okay. (I’m not saying the church is a cult- I’m just saying that I had all the characteristics of a cult member).

I did a ton of work, and counseling, to re-claim my agency. This year I embraced having “high-agency” and I gave myself permission to do absolutely anything that I want to. It’s been great. I was worried that if I allowed myself this “high agency” that I too would become immoral, selfish, and odious – so the parameters that I set for myself were: “I can do absolutely anything I want to… as long as I’m willing to own that decision and accept the consequences of my decisions.” Pausing to think about my values and the consequences of my actions has allowed me to live a life full of freedom, without becoming an odious monster. I highly recommend it.

For the question of religious leaders being able to succeed because they act with “high agency”, I think it’s accurate. It’s the old, “You can’t make an omelet without cracking a few eggs.” As far as the morality of their actions- I think that it’s very easy to start acting immoral when you feel like you can do anything, so I think there is danger in having “high agency”.

One last thought is that I believe one of the purposes of this life is to develop and expand our agency. I think it should be everyone’s goal to expand their agency to have “high agency” (even though it’s dangerous), but the goal should be to expand the choices that are available to you and also be able to handle that power responsibly. (I don’t think you grow your agency by “obedience”, I think you grow your agency by developing your morality).

Hmmm. Here’s the deal with the scarf. Things in the lost & found of a hotel have a very high probability of never being claimed. After all, the traveler is passing through, not local. They may not have any idea where they left the scarf, or even notice that it’s gone. I’ve also discovered that even if you call immediately after realizing that you left something in your room (e.g. that same day, before their check-in time), it is almost never reported by the housekeeping staff. They must be either tossing or keeping those items on the whole. Ergo, the lost & found is sort of de facto, per societal norms, up for grabs. Often, items in the L&F are donated to charity (or kept by hotel staff) after 30 days, so again, it’s not usually going back to the owner.

Maybe high agency just means good at rationalization, but norms that are essentially groupthink binding us do minimize the choices available to us if we let them. I’ll have to think about this some more. We’ve discovered through the current presidency (and Nelson also has behaved this way at times) that if you think highly of your own abilities and don’t care about social norms or impacts to the lesser humans you see as beneath you, you can get a lot done, whether that’s destructive or positive.

John Dehlin’s description doesn’t take into account the charismatic elements of the organization that Joseph Smith started–revelations, miracles, transformation, etc. Yes, organizations can thrive without those elements–but the one that Joseph started claims to be founded upon them.

Andrew S.,

I appreciate your explanation and the articles you linked. These help me better understand the context of your questions.

I agree with Dave B. that our judgment of a “high agency” leader is going to be driven by the realized outcomes. However, I think the “high agency” definition applied to business leaders assumes business success and these are easily measured. Dislike Elon Musk’s methods but he is very successful not only in achieving great technical success but also in producing favorable financial outcomes for investors. Bill Gates was similar. A man who bent the rules of business and was very demanding of employees but he and his company and employees and shareholders realized tremendous success. Steve Jobs is especially recognized at breaking the rules of computer design. Jobs was such a rule breaker he was fired from Apple- the company he founded – for disagreeing with the board. He later returned and his designs made Apple the most successful company in the world. Jobs was also notorious for being demanding and difficult.

Judging religious leaders is more nuanced. What defines success? What constitutes failure? How do we assess a person who has a mix of great success and awful failure? Joseph Smith was a religious visionary but he struggled as an organizational leader. I think Smith saying (or being said to have said) “I teach them correct principles and they govern themselves” is indicative of Smith recognizing this limitations as a leader. I think one of Joseph Smith’s weakness was not caring about the details of organizational functions. He was an idea man and he would rather be chasing a new idea than deal with the daily grind of the “business” of organizing people and running a church.

Observe that Brigham Young was the opposite of Smith! Brigham Young was an organizational genius especially in that Young understood how to build a powerful organization that could serve his ambitions. I am more willing to assign the “high agency” label to Brigham Young than I am to Joseph Smith. The “Mormon Church” exists today as a we know it because of Brigham Young. This also means the hierarchy and supreme authority of the church president exists today because of Brigham Young.

So it is a fascinating question to consider what liberty / agency does an LDS leader have in the church? The church president is legally empowered to do anything he wants with the church and its resources. But what can he do and keep the church membership with him? Joseph Smith took too many liberties – he was too erratic, too impulsive – and he lost the confidence of his associates. Young also took liberties but he was disciplined and determined in his control of the organization and this allowed him to succeed.

aporetic1,

Does this mean that you’d be OK with breaking laws as long as you’re “willing to own that decision and accept the consequences of [your] decisions”? (And those consequences may be jailtime, but you have to get caught and the government has to successfully convict you.)

One of the things that I think about is that when we think of the “ideal” of a “good” prophet, then I think we want prophets that are not bound to the injustices of their era. So, I think that we want prophets who can identify bad laws who will flout those.

If this is the case, then from a societal point of view, that person may be acting selfish, immoral, and odious. But if we agree with them, we would say they are speaking truth to power, are defying an unjust system, etc.,

I love this. I will need to write another post about the “An Inconvenient Faith” documentary, because one of the biggest criticisms I heard from exmormons was something like, “This isn’t the church. What these people believe in is their own private interpretation of Mormonism that wouldn’t agree with what is preached from the pulpit.”

But my reflection to this criticism has always been: Yes, that’s the point. They build up a sense of independence so they don’t need institutional approval. They don’t grow their agency by obedience!

Hawkgrrrl,

In the discussions online, there were a lot of comments like this. And yes, the retort back almost always was: these are just rationalizations. And yet…people get stuff done and we often let the ends justify the means.

Jack,

As least for John Dehlin’s comparison, he was comparing to other religious leaders and founders. As much as we may not believe in or like competing religions (e.g., Scientology, Jehovah’s Witnesses, or even just fundamentalist LDS sects), their leaders also seem able to convince their followers of revelations, miracles, transformations.

I’d say that even in the discussion of otherwise “secular” candidates of high agency, we can often see that these individuals actually often instantiate a lot of the concepts of religion as well. Britt Hartley has a few videos talking about “New American Faiths” and then relating how we would map religious notions to them. I think for Elon Musk (for example), she accurately assesses that he has made technnology into religion. The existential crisis of leaving a doomed planet earth, discovering artificial general intelligence, uncovering immortality through technology…these are still religious things.

It doesn’t matter whether these things actually end up being true. The charisma just means that people need to be convinced to believe in these things and be committed to dedicating their lives to those goals and ideals.

A Disciple,

Thanks for checking out the articles and chiming in again.

I’d actually push back a little bit.

There are a fwe points I’d make about all of these individuals. Firstly, I think they are all example of high agency individuals. However…

1. “Success” is often a function of hype. E.g., a lot of times, it’s not clear whether Elon Musk actually is successful technically, or is simply great at convincing people in a vision that just needs another funding round, another rocket to blow up, and more time to work things out. Steve Jobs was famously described as having a “reality distortion field”. There’s a lot of discussion about how much of our current economy and shareholder value isn’t necessarily based on real, enduring, sustainable production, but is simply irrational exuberance or hype in promised future potenial (e.g., all the AI stuff).

2. It’s not just that these individuals are notorious for being demanding and difficult. It’s *also* that they are credibly accused of being abusive and callous in pursuit of their goals. But these abuses are tolerated or accepted in light of the goal.

I’d actually say that Elon Musk is not generally known as being a good organizational leader. He is rather known for being a visionary (most probably wouldn’t call it religious, but see my earlier response to Jack as to why I think the case can be made that he is a religious visionary. In fact, many people question Elon’s technical chops. However, what Elon indisputably has done is attracted a lot of extremely smart people and motivated them to work ridiculous hours in service of the visions he has.

In other words, I think it isn’t too much of a stretch to judge tech visionaries similarly to how we judge “traditional” religious visionaries. It’s just that most religions aren’t trying to be publicly traded companies.

(I think that high agency can manifest in multiple ways — in “ideas” people and in “organizational geniuses”. I think both Joseph and Brigham are high agency individuals. The fact that Brigham *followed* Joseph and continued his legacy rather than starting something out of whole cloth tells me that Joseph didn’t lose the confidence of *all* of his associates.)

Such an interesting and thought provoking essay for me. One of the thoughts that kept coming back to me was accounts from the history of the lifting of the priesthood and temple ban where, whenever someone among the Q15 (like Hugh B. Brown) would say that we should be working towards lifting the ban and one of his colleagues would say that they couldn’t do it without a “revelation.” In an alternate universe, how different does the church’s history look if the Q15 had taken a more “agential” attitude saying something like we can see that desegregation is good, so we will move to lift the ban and, if God doesn’t want us to do this good thing, then He will have to send a revelation to keep the status quo.

I have a hard time with folks like this. Many behave unethically. Like, back in college, when a guy was explaining how awesome it was to put purchases on credit cards, not pay the bill, and then only have to pay a small fraction of the cost once the debt collectors come calling. He was a genius for working the system, right? What about another guy who insisted you should never pay late fees–just call and complain enough and they’ll drop it! Every. Single. Time! Another guy who insisted that you never pay full price for anything, you can *always* negotiate a discount, regardless of the context. Some of these guys are church leaders, who learn about this crap in their day-jobs. If we just double our expectations, then our faith will produce the miracle! No, the church members who you tasked with those projects have to somehow “manifest” the stupid unrealistic vision of the “inspired” church leader. This is how you use people, manipulate the system, and burn bridges. And a lot of these guys (yes, almost always men) still end up on top because that’s just life.

“Does this mean that you’d be OK with breaking laws as long as you’re “willing to own that decision and accept the consequences of [your] decisions”? (And those consequences may be jailtime, but you have to get caught and the government has to successfully convict you.)”

I believe it was Christopher Hitchens who said (paraphrasing) he murdered and raped as much as he wanted to; he just didn’t want to murder and rape.

It doesn’t follow that if someone is willing to accept the consequences of breaking laws that they’re disposed to illegal behavior. There’s the theoretical assuming of consequences and then there’s personal ethics with their own strong inhibiting qualities irrespective of adversities.

I wonder what level of agency we’d classify church leadership at. JS and BY were high agency. They pushed for things and got them. They innovated, they broke things. They got people whipped into doing what they wanted. If things weren’t working, they could turn the ship pretty easily because they established themselves as the authority figure. I don’t get that same sense from church leaders today. In fact, based on listening to people like Greg Prince and other interviews, I get the sense that the Q15 are largely benign. Yes, they build temples, but they can’t really make change because they are always waiting to be instructed from God and then also waiting to be unanimous. Greg even mentioned in a recent interview that a previous church president (Lee maybe?) re-did church internal governance so that it would no longer be hobbled by a incapacitated president. But, that effectively also killed grass roots change or any other really serious process for change, which is unfortunate because a lot of what we have came from grass roots efforts. Now it is solely top down. The church is also very much focused on image, which, in my experience, typically leads to a lower level of agency.

History tends to forget those who just fall in line. I think we could probably trace all the conveniences we have today back to someone who exercised high agency. I’m curious though, where would you put someone like Hitler (yes, extreme example) on the spectrum of agency? I kind of feel like he was driven by fear so in a sense, his actions were controlled by that as opposed to being free to think or action on his own. JS and BY were more free, maybe, and acted accordingly.

I agree with Mary Ann, people like this get what they want by walking all over others. They are not nice or fun to be around. Other people pay a high price for their success and they often get off Scott free for all the laws they break and people they harm. Elon, well my two kids who work for the government are currently paying the price for his short government stint of going in and taking an ax to everything. He did not save the government money. The government is now paying people not to work because they took his early retirement. Meanwhile, people are forced back into the office and ..um…there isn’t an office, because to save money a few years ago they started working from home so the government didn’t have to build a new building, so their office is a desk in the hall of an old building full of black mold. All Musk did was cause chaos and it will cost billions in the long run. SOOOO brilliant and inspired. A kindergartener could have done a better job. So, now the too few people to process your income taxes are suffering at increased stress levels, trying to cover 3 people’s jobs, and working in crowded office conditions, and a lot of the trained people were close enough to retirement that they took the early out, they will have to be replaced at greater cost while they are being paid not to work. Isn’t this just great?

And Musk is really really good at blowing up rockets. Should he EVER be trusted with manned space flights? Oh, he can make a good excuse each explosion, and keep his investors happy.

But other people pay for his success, not him. Just like with Joseph Smith. Like who really paid for the publishing of the BoM? It left Martin Harris broke, but who’s the hero and who went down in history as the dummy with the nagging wife? His wife was the only smart one. Who paid for Joseph’s banking “brilliant idea “ where he bent the rules? Who paid the most for Joseph not being able to keep his britches buttoned up? It always seems to be the people who trust these guys who end up paying the most, while these sweet talking psychopaths end up with the credit.

There is a book I read years ago where the guy talks about this kind of person with the psychopathic traits who are big successes in business or religious leaders. They are not “high agency” they are borderline psychopaths who are smart enough and charming enough to know what rules they can get away with breaking and are good at talking themselves out of trouble. Sure, some of them have brilliant ideas and a few of them are very successful. Very few are very successful. But there is for sure a pattern of behavior of thinking they can do what they want and that the rules don’t apply to them.

This is just a new word to make “selfish” sound “smart”. Nope, not buying that “high agency” is a new concept. It is just a new word for the same old selfish. Elon Musk is one of the most selfish, egotistical jerks I can name. Yes, he has made a LOT of money off of being a charming, self centered, egotistical, ass. But I don’t think we should be encouraging anyone to act like he does. It is not a new concept or new personality type. Just new words for the same old psychopathic behavior of walking on others to get ahead.

I’m curious about which technology Musk invented? I grant he’s a shrewd investor, although ask the Greatest Generation how buying land in Florida worked out for them, although return on investment often is a matter of luck. As far as I can tell, Musk bought his businesses. Rocket technology? nope. Electronic and satellite communication system? nope. Electrical vehicles? nope. Batteries? nope. PayPal? maybe…although that’s a service and not a technology.

“Does this mean that you’d be OK with breaking laws as long as you’re “willing to own that decision and accept the consequences of [your] decisions”? I used to have a bishop who was known to be a major lead foot. He would honestly leave for meetings at the church building with only 5 minutes to make the 10+ minute drive, and he usually arrived on time through a combination of speeding (all residential areas) and running red lights. When ward members confronted him about his “reckless” driving and didn’t he believe in obeying the law, he said he did obey the law–he paid all his speeding tickets. While I don’t think speeding or occasionally running a dark yellow light are such horrible transgressions, he was also lucky that he didn’t hit a pedestrian or cyclist. He would say there was never any danger of that because he was such a good driver, but again, was he? Or was he just lucky? Unexpected things happen.

And the other issue with traffic laws is that they *are* sometimes not in fact for safety, but are really just nuisance laws to fill the coffers of the local PD through tickets. Anyone who’s driven through Beaver, UT knows that.

I’m as anti-Trump as they come, but he has pointed out (through his willingness to flout the laws & norms that govern us) that these things are really just agreements, and when one party refuses to play along, well, what are we really going to do about it? Within Trump world there are no negative consequences to him for this–he’s cheered on for it. JS also created an isolated society in which his word was the law, in which societal norms were flouted. And then BY did the same thing by leaving the US to pursue his own vision so he would not be constrained by others.

Re: breaking the law, so far people have mentioned “bad” examples that moral people would be aghast at. But I’m still thinking through examples of “bad laws” that should be defied.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, laws such as the Fugitive Slave Act required that captured slaves be returned to their masters (and that Free states were required to comply.)

We are informed that we should be compliant with police officers and agents like ICE, and that obstructing them is criminal.

Ok, so maybe defiance is ok, as long as we are nice about it.

Hawkgrrrl’s latest comment astutely notes that in the political climate we have currently, the administration doesn’t care about due process, norms, institutions. What can challenge that?

@Andrew S.

One clarification I should make is that when I say, “I can do absolutely anything I want to… as long as I’m willing to own that decision and accept the consequences of my decisions.” I guess I wouldn’t recommend this universally. And I don’t think that owning and accepting consequences makes an action become moral.

I was speaking about my change in mindset, where before, I didn’t feel like I COULD do a whole lot of things. Like I physically couldn’t get myself to buy a cup of coffee… and there were 1,000 other things where I was like, I CAN’T do that (it’s not an option). Now, I CAN do that (it is an option)- and thinking about owning the consequences helps me make good decisions.

@Hawkgrrrl As for speeding, yes, I would be willing to accept and pay the ticket if I got caught speeding, but I choose not to speed (especially through residential areas) because I’m not okay with the consequence of potentially hurting someone.