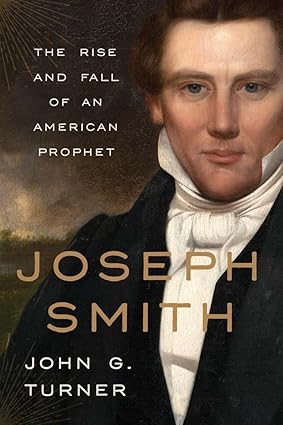

As promised, here is a first post on John Turner’s Joseph Smith: The Rise and Fall of an American Prophet (Yale Univ. Press, 2025). This is about as good an objective biography (neither anti- nor apologetic) of Joseph Smith as we’re going to get. It comes in with under 400 pages of text, making it readable in a way that Rough Stone Rolling wasn’t. Go read my earlier post Is It Worth Reading Mormon History? for a few historical preliminaries.

I imagine most readers are fairly familiar with the Joseph Smith story in New York (First Vision, angels and plates, seer stones and Book of Mormon text, founding of the LDS Church). So rather than try to summarize the book’s narrative, I will below list a few quotations that jumped out at me as I read the book, about one per chapter, along with my commentary.

“Smith’s enduring success was unlikely in the extreme” (p. 3). With little formal education, he authored (dictated, translated, whatever) a book that remains both popular and controversial two hundred years later, founded a church that continues to grow, and established a city in Illinois that for a brief period rivalled Chicago in size. His notoriety, along with his controversial legacy, is why we continue to get new biographies of him. It’s why a historian like Turner undertakes yet another JS biography.

Young Joseph “could feel nothing” at religious revivals (p. 21). “I will take my Bible and go out into the woods and learn more in two hours than you could if you were to go to meeting two years” (p. 28). You might call this the pre-charismatic Joseph, one that most of us might strongly agree with. I am not at all attracted to modern-day Evangelical over-the-top emotional preaching or Evangelical Jesus rock services. I am inclined to think most of us would learn more from reading a modern New Testament translation for two hours than by attending LDS adult Sunday School class for two years.

I’m going to throw in a longer quotation from Chapter 3, “Plates,” to show the author’s direct approach to controversial issues, in this case whether Joseph had actual ancient plates or some sort of object that he fashioned himself. After briefly giving the pros and cons, Turner states:

Along with an acknowledgment of the scanty evidence for this critical episode in Joseph Smith’s life, readers deserve an author’s best sense of what transpired. In this case, it is that Joseph did not have the golden plates. When someone refuses to show a hidden, valuable object to others, the simplest explanation is that he does not possess it. (p. 40)

So Turner is laying his cards on the table. Mainstream Mormons are quite likely to disagree on the existence of ancient plates, while most non-LDS readers find Turner’s tentative conclusion rather obvious. But by noting “scanty evidence” and clearly labeling his conclusion as an opinion, Turner doesn’t force mainstream LDS readers into a corner. I’m sure he wants mainstream Mormons to be comfortable buying and reading his book.

“Saunders and other neighbors confirmed Lucy Harris’s allegation that her husband beat her” (p. 41). Martin Harris is not a particularly sympathetic figure. Here’s an interesting quotation:

On one visit to the Smith house, Harris lost a pin with which he had been picking his teeth. No one could find it. “Take your stone,” Harris requested. Joseph took one of his seer stones, placed it in his “old white hat — and placed his face in the hat.” Then, without looking, Joseph reached out his hand and found the missing pin. (p. 41-42)

That sure sounds like a con. Martin wasn’t just a wife-beater, he was a gullible wife-beater.

“The three men — Harris, Cowdery, and David Whitmer — signed a statement, probably composed by Cowdery, stating that an angel had shown them the plates and the engravings on them” (p. 59). I’ve never seen an attribution of authorship of the Three Witnesses text before. Cowdery is a reasonable guess, but the “probably” in the quotation shows it’s just a guess. But let’s be clear: there are not three witness statements. The details each gave in other places, noted in Turner’s discussion, are not identical. I am aware of no document that Cowdery or some other person actually drafted and the three men actually signed, contrary to what Turner states in the quotation (“signed a statement”). All we have is a printed text at the front of the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon, with the names of the three men printed below it. For all we know, one or more of them might have been initially surprised by the printed statement, either because it left out things they experienced or because it offered statements or conclusions not part of their experience.

Joseph Smith “is the most successful creator of scripture in American history by a wide margin” (p. 71). On the other hand, as the reader is no doubt aware, the Book of Mormon remains controversial, even within the Church. Turner does not dwell on this, but offers a short paragraph signaling the book’s shaky status:

Archeologists have not discovered sites or inscriptions that closely match the Book of Mormon narrative. The DNA of Indigenous Americans does not reveal Hebraic ancestry. Linguistic elements of the Book of Mormon that resemble Hebrew could reflect the influence of the Bible, not original elements of Jaredite or Nephite culture. There are also a host of anachronisms in the text, from the presence of horses in ancient American civilizations to the incorporation of New Testament material in portions that predate those texts. (p. 67)

He adds the understated conclusion that “the consensus of non-Latter-day Saint experts is that the Book of Mormon’s narratives are fictional rather than historical.” In a footnote he adds that “Latter-day Saint scholars have intelligent answers to many of these objections.” A minor quibble here: it’s not like there are two separate and distinct camps of scholars, LDS who defend the party line and non-LDS who uniformly reject the Church’s many claims for the book. There are LDS scholars who reject some LDS claims and there is a range of opinion among non-LDS scholars who criticize it (on various grounds).

“Joseph had stopped using his seer stone as a conduit for his revelations. He now dictated the words of the Lord in a trance-like state without the stone, hat, or any other device” (p. 82). This was toward the end of 1830. Most commentators sort of breeze over this shift, as if it’s just the normal thing for a Christian prophet to do, a regular occurrence, an established procedure. Not at all. The use of seer stones in this context is unique. There is no clear rationale offered by the Church for why Joseph needed seer stones in the first place or why, if they were so effective at channeling God’s will or a stream of words, that Joseph ever set them aside. Until recently, the Church worked hard to avoid any discussion of seer stones.

The fact that no succeeding senior LDS leader (deemed “prophets, seers, and revelators”) has successfully used a seer stone as Joseph did seems to undercut the whole notion that there was any efficacy to any seer stone. It’s not like LDS Presidents, upon taking office, undertake a “seer stone year” to get the hang of doing revelation, then set them aside. The only LDS official to use the seer stone method other than Joseph was Hiram Page, and Joseph rejected his writings/revelations as spurious (discussed by Turner at p. 82).

These quotes are from the first hundred pages of the text and take us to the dawn of 1831, when Joseph and most of the early Mormon converts relocate to Ohio. I’ll cover the Ohio and Missouri material in my next post, followed by a third post on the momentous Nauvoo period.

Dave B,

Thanks for sharing this summary. I hope to read this book this weekend.

My perspective is the founding of the church changed Joseph Smith and the longer Smith was involved in “building Zion” the more distant he became from the “boy prophet” he once was. A thing that stands out to me is how different the Doctrine & Covenants reads from the Book of Mormon, especially after 1830. First there was the move to Kirtland and then the focus on establishing Zion in Missouri. These activities consumed Smith and I believe changed him, or otherwise brought out character traits that clouded his prophetic gift.

For after 1830 Smith changed from being a prophet – meaning a person who reveals God’s word – to being a promoter who constantly gave his followers something to believe even when the last promise went unfulfilled. The LDS mythology of Joseph Smith is that he was persecuted and this is the reason for his struggles. A more truthful history is that Smith was a charismatic yet erratic leader and he constantly over promised and under delivered, and then blamed others for falling short. But give Joseph Smith credit for always trying again, and again, and again, until he ran out of friends who would protect and cover for him.

Back to the “boy prophet” role, The Book of Mormon is in a different language than the Doctrine & Covenants. What explains this? A simple obvious example is the word “plainness”. This word is used 10 times in The Book of Mormon and is a favorite word of Nephi and commonly used in the “Small Plates” of The Book of Mormon. The word appears once in the Doctrine & Covenants and it is in section 133 that was written in November 1831. As I mentioned, once Smith got involved in “building Zion” it seems the Lord no longer prioritized plainness, and in fact the religion taught by Joseph Smith became increasingly complicated.

The problem with explaining away The Book of Mormon is that there no rational explanation. If Joseph Smith wrote it he did it with a grammar and vocabulary that was unique to him. If others wrote it you have the mystery of who and how did the subterfuge escape discovery?

John G. Turner has been criticized as an apologist (from the x Mormon folks) and as anti-LDS by some believers (or so he claimed on Mormon Stories). And my reading of the book pushes me to believe that I can see a reason for both of these criticisms. You are usually doing a pretty good job as an historian if you can get both sides to criticize you. So I give credit to the author for this. However, I don’t know whether this is evidence that he is a thorough and fair historian or whether he is an author who knows how to sell books.

“He now dictated the words of the Lord”

IDK, Terryl Givens called that “absurd and childish,” so I’m not sure whether it’s a faithful or unfaithful perspective.

Regardless, I’ve been impressed with what I’ve read of the book so far. Turner’s writing style seems so…readable? A bit odd, when you consider this was published by a university press and Rough Stone Rolling was a “popular” work.

Joseph’s usage of seer stones shows a perfect progression as he matured as a seer.

He starts off using them in ways that were common according to the folklore of the time and place.

When he gets the interpreters that came with the plates he learns to use such devices in ways that are more appropriate to the purposes of the Kingdom.

After which he uses his own seer stone in a way that demonstrates fluency in his gift.

He finally matures in his gift of seership to the degree that he no longer relies on such devices; it’s as if his own mind becomes a veritable urim and thummim.

All of that said, it should be noted that the scriptures point to the idea that every faithful latter-day saint may become as fluent as Joseph was in the spirit of prophecy and revelation given enough time and experience on their part.

I just finished listening to the Smith-Pettit Lecture Dr. Turner gave at this year’s Sunstone Symposium. In compressing the substance of this biography into a single-hour address, Turner focused on the alliterative parallel of “plates and polygamy.” He drew behavioral comparisons between the younger Joseph claiming to possess the golden plates and an older Joseph rolling out polygamy. Interesting to see his observations on Smith’s risk taking, the leader’s willingness to double down, and his practice of crafting revelations convenient to his needs at the time.

It’s great to see a new biography out from an accomplished scholar–especially one who is an outsider and poised to be objective. Having listened to his Sunstone address, and especially his lively Q&A after, I appreciate Turner’s flair for good communication and relatability. Some scholars are able to synthesize incredible amounts of research in their own mind but fail to turn that knowledge into accessible prose. Not sure if or when I’ll have the time to read this latest biography, but the buzz seems really good. Thank you for the initial summary, Dave B.

A comprehensive Jewish polemic against the theological foundations of Xtianity and Islam. Where was JeZeus throughout the Shoah? Where was Allah throughout the Nakba total defeat disasters of ’48, ’67, & most recently the 12 Day War?

Explain how the local tribal god of Sinai who dwells in the Mishkan Yatzir Ha-Tov/strictly and only within the hearts of the chosen Cohen seed of Avraham, Yitzak, and Yaacov – upon this Earth, does eternally judge the Monotheistic Universal Gods of Golgotha (place of the skull) and Mecca & Medina who occupy the Heavens – as false Baal Gods of Av Tuma avoda zarah – no different from the Gods worshipped by Par’o and Egypt or the Gods worshipped by the Canaanites.

The Torah’s God is not a distant “universal father” but the local, tribal Elohim of Sinai, who entered history through the brit cut between the pieces with Avraham, promising land and seed to Israel alone. This God judges all nations but resides only in the mishkan (tabernacle) of Jewish hearts committed to tohorah and tzedek (justice). Monotheism’s universalism profanes this faith that pursues justice within the borders of the oath brit lands, by inventing heavenly overlords who demand submission from all humanity, violating the Second Commandment: “You shall have no other gods before Me”, which explicitly condemns the polytheistic undertones of trinitarian Christianity and the absolutist Allah of Islam as echoes of Ba’al worship—gods of storm, fertility, or conquest that promise salvation but deliver tumah.

JeZeus as a Protocols of the Elders of Zion NT blood libel slander, did not know the fundamental distinction which separates Torah common law from Roman Statute Law. Likewise his similar Nathan of Gaza who served as the disciple of Shabbetai Tzvi … commonly known in NT rhetoric propaganda as “the Apostle Paul”. To sanctify the mitzva of shabbat (all Torah commandments apply equally to all chosen Cohen seed of the Avot – including the mitzva of Moshiach) requires making the הבדלה distinction between time-oriented Av commandments from toldot positive & negative commandments which do not require k’vanna; this בינה that discerns like from like מלאכה מן עבודה, separates holy from profane – t’ruma from chol. The imaginary man JeZeus did not “understand” the mitzva of shabbat any more than do Xtians understand the mitzva of Moshiach or Muslims understand the mitzva of Torah prophets; Torah prophets command mussar – T’NaCH does not instruct history because prophesy as a mussar rebuke applies equally straight across the board to all generations of the chosen Cohen seed of the Avot, no different than Shabbat and Moshiach.

The dedication of the House of Aaron as Moshiach serves as the Av precedent for all other Moshiach dedications thereafter. The precedent for korbanot learns from the rejection of Cain’s korban. A Torah korban exists as a time-oriented commandment which requires the “wisdom” of k’vanna-swearing a Torah oath through שם ומלכות. The term מלכות refers to the king-like leadership direction of the 13 tohor Oral Torah spirits which Moshe Rabbeinu perceived at Horev 40 days following the sin of the Golden Calf av definition of all avoda zarah for all generations. The Oral Torah revelation occurred on Yom Kippor wherein HaShem remembered the oaths sworn unto the Avot and annulled the vow to make from Moshe the father for the chosen Cohen people. Just as brit does not translate correctly as covenant, so too and how much more so t’shuva does not correctly translate as repentance for sin. Torah faith does not atone for sin, Yom Kippor makes atonement for a failure to rule the oath sworn lands with righteous judicial common law Sanhedrin justice which makes fair restitution of damages inflicted by bnai brit upon bnai brit. Aaron as the first anointed Moshiach – dedicates through the sanctification of korbanot the righteous pursuit of judicial justice among the chosen Cohen seed of the Avot within the borders of Judea.

Matthew genealogy traces the lineage of its Harry Potter through Joseph. Luke’s genealogy traces its lineage through Mary. LOL. Matthew lists 42 generations while Luke lists 77 generations! Matthew begins with Avraham and moves forward while Luke begins with Adam. The final name in Matthew’s genealogy Joseph (husband of Mary). While Luke ends with JeZeus. Matthew follows Solomon’s line; Luke follows Nathan’s line. All gospel Roman forgeries fail to grasp the Torah negative commandment of a “bastard child”.

The gospel of Luke ignores that all Goyim reject to this day the revelation of the Torah at Sinai. No gospel forgery ever once includes the 1st Commandment revelation of HaShem who dwells thereafter only within the Yatzir Ha-Tov of the hearts of the Chosen Cohen seed of Avraham Yitzak and Yaacov – brit cut between the pieces. Nathan, another descendant of David not tied to the kingship.

Anymore than the gospels has any linkage to the Torah dedication of the mitzva of Moshiach – based upon king David’s failure to judge the Case of Bat Sheva’s husband with justice. Ruling the land/people with righteous judicial justice defines the Torah intent of the mitzva of Moshiach. Luke’s attempt to make its false messiah into an av tuma Universal messiah for all Mankind, violates the revelation of the Torah at Sinai.

Moshe first anointed the House of Aaron as Moshiach. Aaron stands on the foundation of Elohim acceptance of the sacrifice dedicated by Hevel, despite Cain being born first. This theme duplicated again and again in Yishmael/Yitzak, Esau\Yaacov, Reuven\Yosef, pre-sin of Golden Calf first born of Israel/post Golden Calf tribe of Levi. The Luke/puke contradicts JeZeus’s declaration to the Samaritan woman! Hence the NT compare more to a superman comic book than an actual replacement of the brit chosen Cohen seed of the Avot replaced by a Roman fictional Harry Potter messiah.

The greatest flaw of the gospel forgeries, hands down without any question, their utter replacement theological failure which fails to grasp that all the Torah mitzvot revealed at Sinai apply equally – straight across the board – like shabbat and tohorat Ha-beit for married women – to all generations of the chosen Cohen seed of Avraham Yitzak and Yaacov.

Furthermore the JeZeus false messiah failed to differentiate the Avot in Genesis perception of El, Elohim, El Shaddai etc as a God in the Heavens from the revelation of HaShem in the 1st Sinai Commandment wherein the Divine Presence middot revealed to Moshe after the sin of the Golden Calf on Yom Kippur live in this Earth only within the hearts of the Yatzir Ha-Tov Cohen people. When the followers of the Harry Potter false messiah asked their God how to pray he taught them: Our Father who is in Heaven … this fundamentally violates and profanes the revelation of the Torah at Sinai – the Spirits of HaShem live within the Tabernacle of the Yatzir Ha-Tov within the bnai brit Cohen hearts.

Tefillah – Kre’a Shma – Hear Israel HaShem Elohynu HaShem Echad. The word One does not refer as the av tuma avoda zara theologies promoted by the NT and Koran false prophet frauds of Universal Monotheism. Monotheism violates the 2nd Sinai Commandment; HaShem sent Moshe to Egypt to judge the Gods of Egypt! Rather the word ONE refers to the oath that a Cohen swears through his tefillen to remember the oaths sworn by Avraham Yitzak and Yaacov wherein the Avot cut an oath alliance to father the chosen Cohen people. Hence the 3 Divine Names in this one verse have the intention to remember the oaths the Avot swore to father the chosen Cohen seed for all eternity. Furthermore, the name Elohynu judges and separates HaShem from HaShem; acceptance of the Written and Oral Torah revelation לשמה.

The father determines the genealogy of both sons of Aaron and Kings of both Yechuda and Israel. The NT fraud has no concept that once a man acquires title to the O’lam Ha’bah (future born children) of his wife, that even if Zeus himself fathered Hercules that under Torah law Hercules constitutes a bastard. That the beating of JeZeus almost to death and torturing him upon a cross compares to offering a deformed animal on an altar as a Torah sacrifice. תורה לא בשמים – a direct quote from the Book of D’varim which defines the revelation of the First Sinai Commandment for all eternity thereafter. JeZeus depicted as the “Son of God/virgin birth” … a bastard child forever excluded כרת from the seed of the Avot chosen Cohen people.

The brutal murder of fictional Harry Potter JeZeus through judicial corruption and injustice totally the opposite of Moshe dedication of the House of Aaron as Moshiach. The prophet Shmuel first anointed Shaul of the tribe of Binyamin as Moshiach, but his failure to pursue justice – specifically in the mitzva of Amalek (understood as Jewish ערב רב – assimilated Jews who follow foreign cultures & customs who intermarry with Goyim who reject the revelation of the Torah at Sinai.) Amalek or antisemitism plagues all generations of Jews with Torah curses no different than the plague curses in Egypt.

Superficially Yonah sent to “warn” the king of Assyria. But Torah prophets serve only as the mussar police of Sanhedrin courtroom rulings. The Sanhedrin courts only have jurisdiction within the borders of Judea. Hence for the prophet Yona sent to Assyria his mission replicates that of Moshe in Egypt sent to cause the exiled 10 tribes of Israel to remember the brit oath sworn to the Avot. Assyria conquered shortly after Yonah commanded his mussar to the exiled seed of the 10 Tribes by the Babylonian empire.

Contrasts the Torah’s depth with the superficial, treif distortions peddled by the church—as epitomized in that 1956 Hollywood spectacle, The Ten Commandments, where a bald Yul Brynner as Pharaoh and a chiseled Charlton Heston as Moshe reduce Sinai to a cinematic farce. The revelation of the Torah at Sinai caused Israel to recoil after hearing only the first two dibrot (statements) directly from HaShem’s tohor spirits.

Understanding why the aseret ha-dibrot (the “Ten Statements,” not “Commandments” as the church mistranslates to fit its legalistic idolatry) appear twice. Israel demanded thereafter that Moshe ascend to receive the remainder of the Torah—Written and Oral—lest these tohor middot consume their Yatzir Ha-Raw tuma middot.

The aseret ha-dibrot repeated twice in the Torah, this duplication, it exposes the root of Torah common law; which stands firmly upon bininei avot—the foundational “building fathers” or precedents that generate an expansive edifice of halachah. As enslaved Israel made bricks to build Egyptian treasure cities, the Talmud employs the building block of Hillel’s 7 middot, Akiva’s 10 middot, Yishmael’s 13 middot, and HaGallilee’s 32 middot; every sugya of Gemara stands upon these יסודי logical building blocks.

These are not mere repetitions for emphasis, as Goyim theologians defame the Talmud as the words of Men, far removed from the Word of God! Rather the concept of T’NaCH prophetic Oral Torah mussar middot and Talmudic halachic middot bridge the gap of holiness which elevates holy to most holy commandments. Shabbat serves as an Av precedent for all other wisdom-commandments which require k’vanna wherein Jews in all generations dedicates tohor Oral Torah middot – which the Talmud calls: מלכות. As the Torah has two grades of commandments the T’NaCH & Talmud judicial common law have two grades of middot.

Torah speaks in the language of Man. The kabbalistic term “shekinah” stands upon the Mishkan precedent. Its not the form of the Mishkan and its vessels which defines the revelation of the Torah at Sinai/Horev; anymore than its the 6 days of Creation משל, but rather the introduction of time oriented commandments נמשל. The נמשל that the רוח הקדוש Oral Torah middot of Horev breath life into the Ya’tzir Ha-Tov of the Chosen Cohen peoples’ hearts. Hence the error spelling of the word heart as לבב in the tefillah דאורייתא acceptance of the yoke of the “kingdom of heaven”.

Meaning remembering the oath sworn by the Avot to father the Chosen Cohen people and the acceptance of the Written and Oral Torahs at Sinai and Horev. Herein designates the k’vanna of the time-oriented wisdom commandment known as קריא שמע. As this commandment applies to all generations of Israel so too the mitzva of Moshiach. Jews do not wait for a fabled 2nd coming of JeZeus. “Time” not as literal hours but as opportune wisdom (as in Ecclesiastes 3:1–8’s “a time for every matter”). Thus the repetition of the 10 dibrot serve to define the elevation of time-oriented commandments as the k’vanna to remember the redemption from Egyptian exile – as expressed in the first Sinai t’shuva commandment.

The revelation of the Oral Torah, according to the kabbalah taught by rabbi Akiva’s פרדס understanding, reveals a dynamic logic variable inductive format, as opposed to the ancient Greek philosophers static rigid syllogism deductive logic. Islam’s sharia mimics toldot without av wisdom, leading to rigid fatawa absent prophetic t’shuva. In essence, the twice-repeated 10 dibrot reveal the Torah’s blueprint for common law: a beniyan av teaching generational renewal, mitzvah classification, and mussar-k’vanna. This stands eternally against the church’s movie myths and Islam’s static codes, affirming Sinai’s wisdom for Israel’s seed alone.