I recently listened to an interesting podcast interview that Ezra Klein did with Yoram Hazony, the Israeli author behind the book “The Virtue of Nationalism” and who founded the NatCon movement that involves MAGA luminaries like JD Vance, Josh Hawley and Marco Rubio. Vance in particular is a proponent of the idea that the US is not a nation based on ideas and shared principles, but is a nation of people descended from European settlers hundreds of years ago who fought and bled on the soil and created the nation we have today. It’s not a nation of ideals, but an ethnic group similar to European nations that are bound by long-standing ties to the land.

I also watched snippets of a fascinating debate on Jubilee, a debating platform with specific rules. In this debate, journalist Mehdi Hasan, who has dual citizenship (US and UK) and is an American immigrant of ten years, debates a group of 20 far right supporters. One of them claims that he is a “native American” because he has ancestors that date back to the 1500s, which is a claim that is easily disproven (the Jamestown settlers are the only ones who would qualify, and they disappeared–a fascinating story that’s part of American history).

I can go toe to toe on ancestral longevity with anyone who isn’t an actual Native American if we want to start whipping out our settler pedigrees. Like a lot of Americans, I have ancestors who were on the Mayflower, and many more who were part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, meaning they pre-dated the United States. These nationalist arguments have become a part of the far right, including the claim by Vance that when he proposed to his wife (definitely not an American to these debaters) he said “I come along with $120,000 worth of law school debt and a cemetery plot in Eastern Kentucky.” Vance continued in his speech to explain his view: “And if, as I hope, my wife and I are eventually laid to rest there, and our kids follow us, there will be seven generations just in that small mountain cemetery plot in eastern Kentucky. Seven generations of people who have fought for this country. Who have built this country. Who have made things in this country. And who would fight and die to protect this country if they were asked to.”

Journalist Alex Wagner took aim at Vance for this speech, calling it an “Easter Egg” of white supremacy:

“One of the things that stuck out to me was when he started talking about what America is, he said that ‘America is not just an idea, it is a group of people with a shared history and a common future.’ The thing about America is that it’s not a group of people with shared history. In fact, I think a lot of people would argue it’s quite the opposite. It’s a lot of people with different histories, different heritages.

And that’s the other piece of it, he goes on, he went on a long sort of paragraph at least about this plot in eastern Kentucky, where his 7 or 6 generations of his family are buried, and his hope is that his wife and he are eventually laid to rest there and their kids follow them. And I sort of understand the idea of sharing the burial plot, but it also is, it reveals someone who believes that the history that the family should inherit, and indeed the history that should be determinative in the story of the Vance family, is the history of the eastern Kentucky Vances and not the Vances from San Diego, which is where his wife is from and where her Indian parents are from. But in America, it doesn’t always have to be the white male lineage that trumps that, that defines the family history, that that branch of the tree supersedes all else.

And I just think the construction of, of this notion reveals a lot about someone who fundamentally believes in the supremacy of whiteness and masculinity, and it’s couched in a sort of halcyon, you know, revisitation of his roots, but it is actually really revealing about what he thinks matters and who America is, and that America is a place for people with his shared Western background. And that is the idea of America, that is the nation of America that he wants to resurrect.”

Wagner points out something interesting in the idea that JD’s family history trumps his wife’s, but also that he views his ancestors as the people that matter in creating this country. It’s a view shared by many on the right currently. And we should be proud of our heritage. It’s a little weird to me that some of those who are most proud of their heritage were on the wrong side of the civil war, though, and we do seem to be relitigating some of those same ideas.

Here’s a contrast of what makes someone an American:

- Shared Ideology, aka The Civic Nationalism Ideal. Being an American means being committed to a shared set of principles, including the rule of law, democracy and representative government, individual rights and freedoms, equality before the law, pluralism, and tolerance. Anyone in the world can become an American once they go through the naturalization process if they agree to uphold the constitution and participate in democracy.

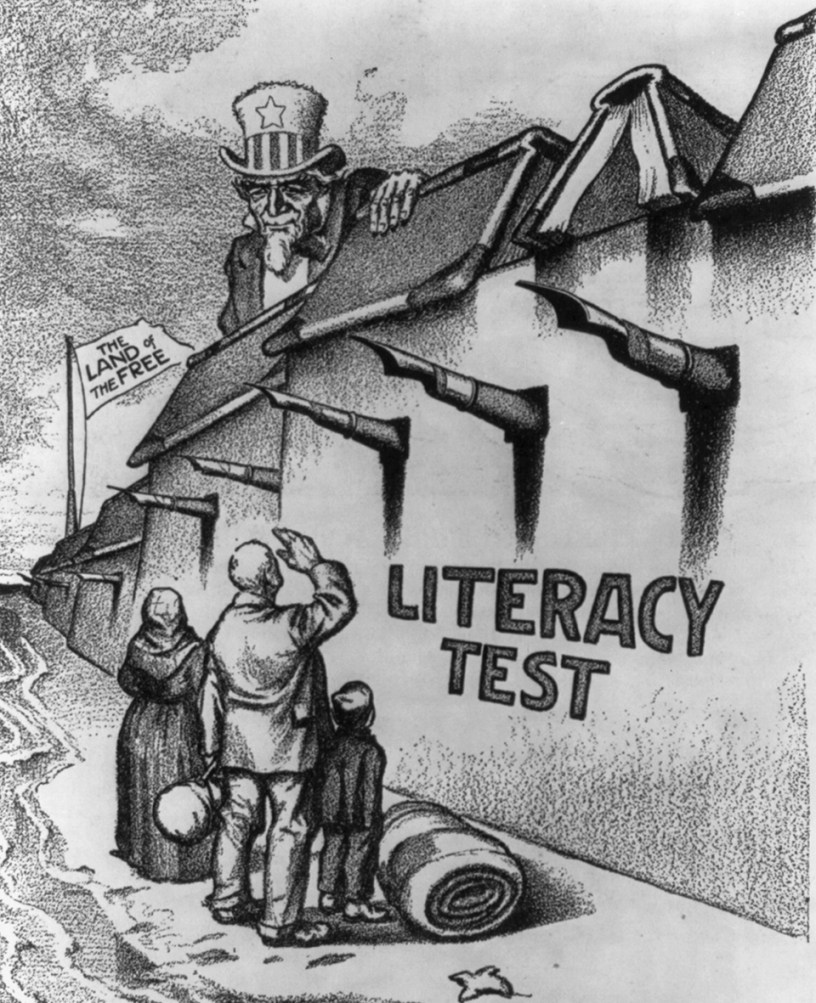

- Ancestry, aka Nativism. Being American is tied to having many generations of American-born ancestors, being part of the dominant culture (white, Christian, Anglo-Saxon roots). This would exclude the millions of naturalized citizens and would also disavow the US as a country of immigrants.

Those who hold to the Ancestry idea are also often strongly invested in a form of culture wars, expecting and requiring such norms as speaking English, the manner and enthusiasm for celebrating American holidays, consuming American media, food, and sports, and participating in cultural debates about rights, and the national direction.

Obama was clear in stating that “What makes someone American in a shared belief in the promise of America–not bloodline, not birthplace.” Trump’s views stand in contrast to Obama’s statement, despite marrying an immigrant. Wagner’s point about only white male lineage mattering, not the immigrant wife, seems to hold true here as well.

“There is nothing so American as our fellowship of immigrants.” Pres. Woodrow Wilson, in an uncharacteristic moment of not sucking

This national discussion reminded me somewhat of a feeling among some church members that not having a long Mormon pedigree made you somehow less Mormon. If you were a convert or your parents were (in my case), if you had no Mormon royalty in your ancestry, or if none of your family tree had ever lived in Utah, or if you had Mormon ancestors, but they were never leaders or polygamists (I guess they were unpopular nobodies?), you were somehow seen as not as Mormon as someone else. Now, let’s be honest, this happens sometimes with one’s Americanness as well, and not only on the far right. It’s why there are groups like Daughters of the American Revolution, or why people brag about having ancestors who were on the Mayflower. [1]

I’m not really sure that most Mormons feel this way or that they would even admit it if they did, but as someone with absolutely no Mormon pedigree, I certainly encountered the attitude from time to time. I’ve even seen this at a local level, which is interesting, in which a certain set of families are the “rock stars” of the ward or stake, and so as their children become adults they just naturally inherit the leadership roles and set the culture of the ward.

- Have you seen this attitude among church members?

- Have you heard these nativist arguments among your acquaintances?

- What are your views about who belongs as an American? What about as a Mormon?

- Do you enjoy these types of debates like I do, hearing the differing perspectives at the extremes? Or do you think it’s risky to platform extremists?

Discuss.

[1] Like I just did, but let’s be clear–the people on the Mayflower were joyless Puritans who policed their neighbors relentlessly. They weren’t exactly the world’s best people, IMO. Has no one read Nathaniel Hawthorne or seen anything about the Salem Witch Trials?

Vance is arguing that America is a shared idea and opportunity that anyone can embrace. His comment about his wife – who is 1st generation American – is to say that despite her family’s brief years as Americans she is just as American as he is.

And so it is in the church. A new convert and a member who is a 5th generation descendant of a Mormon pioneer have equal claim on the blessings of the restored Gospel. I know many of my best church leaders were converts and it mattered not what identity they or their family or ancestors previously had.

Disciple, that is NOT what Vance is saying about his wife. He is saying that for her, as a lowly woman, HE, glorious he, as a man in his patriarchal world makes up for her lack of being a real American. Now compare how your nauseating hero would feel about his sister marrying a naturalized citizen from India and planning on being buried in his family plot back in India. That would be her giving up her status as a real American. The man is a racist pig and even his wife knows it.

And, I am so happy to find a fellow descendent of the Mayflower who is both proud and disgusted in her Puritan ancestry. I have always felt that who our ancestors are is something we cannot be held accountable for. Yes, one of my ancestral lines goes back to the Mayflower, yes some of my ancestors were the ones drowning and hanging “witches”. I have at least one of those girls in that original group who started making accusations as one f my ancestors.

My Mormon ancestry is just as “proud” and just as guilty. Yeah, I have ancestors quoted over the pulpit in general conference. If you have been on Trek, you have heard my gggggrandfather’s journal as the study guide that is read from every night. One gggggrandfather held the keys to the Nauvoo temple when it burned. But, get into Utah history from the Native American perspective and you know that Daughters of the Mormon Pioneers have just as much to be ashamed of as they do to be proud.

Our US history is just as ugly, what with what we did to the people who were here before we came and with slavery.

I have always felt that if you are claiming that your ancestors make you somehow better than others, then you just failed to see the ugly side of your own ancestors.

While I think it is fine to love your heritage, and I love my New England (even the Mayflower part) and Mormon pioneer heritage, you and I have no place thinking your/my heritage is better than anybody else’s. It’s like I love my kids, but they are not better than other people’s kids. Same way, I can love my ancestors as long as I remember they are not better than other people’s ancestors and they certainly do not make me better than other people.

So, love your heritage, but it isn’t better than anybody else’s. And JD Vance being so proud of his hillbilly heritage just makes him an arrogant a**. He can love his heritage if he wants, but his big idiocy is that he thinks his ancestors are better than Native Americans, Mexicans, blacks, and he thinks his better ancestors make him better.

I believe the ideals written in our constitution are what makes us Americans and it is living up to those ideal that makes us great, not skin color or ancestry. It is character that makes a person a great person. The fact that the white nationalists think skin color is more important than character just proves how shallow they are. Skin color is only skin deep. Character is what a person is.

My father is descended from Mormon pioneers and my mother is a convert. I never got the sense that she felt less Mormon for lack of a pedigree, but I do think she feels she missed out on some scriptural knowledge for not having attended semiary in her youth, for example. (Maybe you had to be there to understand how little most of us were paying attention.)

To anyone who believes ancestry is what makes them American, especially JD Vance, I would say, pick a date. What is the date cutoff that your ancestors had to arrive before in order to be a “real” American? Why that date and not, say, today? What fraction of your family tree arrived before that date? Do you even know the answer to that question? How do you justify excluding arrivals after your preferred date?

I have no idea whether anyone I associate with holds to these views of America, but I hope not. Certainly it doesn’t exist in my work life, because I work in a tech company where literally no two members of my team were born in the same country. Most are naturalized citizens of the US, but not all. I want America to be the place where every one of them can be, or come to be, regarded as American every bit as much as I am, with my Mayflower ancestors.

Mormon microcosm of this… I live a small, Southern Utah pioneer town and my heritage goes all the way back. My people and the other early settlers dug the ditches, planted the trees, built the rock homes that are still there, and suffered through the summer heat and the winter wind to eke out a living. They buried their kids there, 8 generations of the family in the cemetery, the whole nine yards. It’s my place, my birthright to be here, as far as I’m concerned.

Fast forward, the advent of modern air conditioning has made this a pretty attractive place to live. Old families selling off their landholdings to cash out. Subdivisions popping up like weeds. Substitute “immigrant” with “California transplant or Wasatch Front snowbird” moving in saying “oh this place is so wonderful” but also changing its character, demanding things, bringing some of their urban tastes and problems with them. Some are LDS, some aren’t, frankly I don’t care whether what they believe, I just find myself frustrated that they all feel the need to move in and change the place. I don’t want there here. It’s not their right to be here.

Then I have to stop myself and wrestle hard with the fact that even though it’s my last name on the headstones, I didn’t dig the ditches or the graves either…

If you are on an elevator that is basically full, you are irritated when it stops on yet another floor and someone wants to get on, making it even more crowded. Your automatic impulse is to say: “wait for the next elevator”.

If you are waiting for an elevator to stop on your floor and it finally arrives, you are really hoping folks will create some space for you to get on even if it is already very crowded. Your automatic impulse is to say “can you just scooch over a little so I can get on”?

The two scenarios above are the same elevator. And in fact, the two quotes above might be said by the exact same person in two different places at two different times.

I too watched the Mehdi Hasan Jubilee “debate” with fascination and horror. They just say the quiet part out loud now. Thankfully my acquaintances, family, and friends don’t say the extreme stuff I heard from the admitted fascists on Jubilee. But many family members are still not great in much of what they say. That said, I think online “debates” have hurt collective discourse as a whole. Political discussion today is all jabs and gotchas. And these debate platforms foster that. Plus too many people who think they know things enter the debate scene. The ones who get attention so so not because of their intellect and profundity but because of their antics. Knowledge of any subject takes time to acquire. People should spend more time working on knowing instead of argumentation. Lawyerism, the sentiment that any point can be argued, has taken over. And it is a crying tragedy.

I think Mormons with a pedigree tend to trust and relate more to other Mormons without a pedigree.

It drives me nuts that, both as Mormons and as Americans, we gush over our pioneer/colonial heritage but will not tolerate modern individual pioneers.

To wit, on the last thread, a comment noted that Brigham Young is a brilliant colonist, notwithstanding that he did not come here to play nice with the locals and in fact acted violently toward them and that he did not come here to assimilate but to bring his hippie free loving 50+ wives with him.

But if a single mom fleeing death threats comes to America seeking asylum, we blame her when the neighbor’s cat going missing. If a foreign convert wants to come to Zion, we tell her Zion is no longer a place but a mindset.

Yesterday’s pioneers are today’s violent criminals.

Make it make sense.

josh h’s point is well taken. As brilliant stated in the “Clueless” high school debate class scene, “And may I remind you that it does not say RSVP on the Statue of Liberty.”

No I don’t like these debates. Hearing humans say the cruelest things for likes really hurts my heart.

If it’s the date of arrival that matters in America, it looks like the Spanish don’t count. St Augustine, Fl., is the oldest continuously inhabited city in the U.S., and Santa Fe is 2nd, which is very near where I have lived for the past 45 years.

Mormon women weren’t allowed in the D.A.R. because of polygamy, but they started the D.U.P. Both organizations were a way for members to feel privileged and superior, even as they did their good works. My GGGrandfather lived in Springville during the infamous Reformation of the 1850s, and left a lengthy journal, which was careful not to say anything negative, except that he didn’t agree with everything that happened, and polygamy was his biggest trial. We will never know the true history of this country or of JS or the pioneers as long as right wing fundamentalists control the narrative.

In the summer of 2019, I wasinvited to give a talk about Pioneer heritage. I shot back with. “Sure, do you mind if I say we don’t need need Pioneer heritage?” Needless to say, the invitation was withdrawn. I wrote the talk, anyway, even though I never delivered it. Here’s an abridged version.

The celebration of Pioneer heritage is a time-honored tradition among the saints. Many are the tales of families who trace their heritage back to those blessed pioneers who made the journey to the Salt Lake Valley in the still unnamed territory.

Moving was not unknown to the saints. They had already left New York, Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois. Those paths had already been if not tamed, civilized. These were all states admitted to the Union with paths and presence of people who had come before. Out west, though, was frontier, the unknown. Saints going to Utah faced: harsh winters, disease, breaking wagons, injuries, and so many others we can scarcely understand them.

I don’t have pioneer heritage. My parents both converted to the church shortly before I was born. When people traced their pioneer heritage, I did not measure up. Somehow, I was not a true saint so long as I did not share in that exclusive heritage. It is something I will never, ever have, either. There were no overt remarks that those who have no pioneer heritage are inferior, but when you don’t have that heritage to celebrate, while others are. . . .

Only later did I realize that pioneer heritage is a good thing when it’s used to promote pioneer spirit. That same spirit of the Saints going to Utah, of the Hebrews following Moses through the desert, is no different than that of investigators accepting the gospel to become baptized. It takes a leap into the unknown. My parents often told me that they didn’t know everything about the church when they accepted baptism. I’m sure the same is true for every convert.

My parents were pioneers. They were the first in their families to become baptized. They set themselves on a path to the unknown, in many respects leaving family behind as that family were not members. And the Church was still unknown to them. They felt lost for a time as the missionaries moved on and they found themselves in a church among strangers with new rules and a new culture. They were out of their element and deeply uncomfortable. This is what it means to be a pioneer.

Christ was a pioneer. He dared to take the Jewish faith and transform it into something greater. What he preached to the Sadducees and Pharisees was a heresy to their orthodox faith. He fed the disciples and healed the sick on the Sabbath (Matt 12). He healed the servant of a centurion (Matt 8); went among the blind (John 9), the sick (Luke 4), the lepers (Luke 17), told an adulteress to sin no more while condemning those who would stone her to death (John 8). The love of God was available to all: Samaritan, Roman, Canaanite, and the peoples of far-off lands the Jews had never trod. Love all neighbors. These teachings are not of comfort and safety.

Pioneer heritage isn’t about celebrating what ancestors did, it’s to inspire us to follow their same spirit to leave comfort and safety behind. It takes courage and faith to do these things, just as Christ did them. Today, the people have different names than in Christ’s time. Today we have: Protestant, Catholic, Baptist, evangelical, Buddhist, atheist, Hindu, Muslim, Wiccan, pagan, agnostic, Republican, Democrat, libertarian, independent, heterosexual, gay, lesbian, transgender, genderfluid, Yankees, rednecks, cowboys, Texans, too-polite Canadians, Floridians, alcohol-drinkers, substance-users, Jell-O eaters, and people who don’t like root beer. That last makes me especially uncomfortable.

What the pioneers did was remarkable, and took amazing faith, courage, and perseverance. But the best way to truly honor what they did is for us to be pioneers ourselves, to show that we have inherited that pioneer spirit. Christ left us a challenge to be pioneers, to go among those who make us uncomfortable and to love them, personally, as he did, as they are, for who they are.

a3writer – good on you. You should have just accepted the invite to speak (w/o the caveat), then delivered your talk as written, since it DOES completely address whatever we are signifying when we use the term ‘Pioneer Spirit’. I am confident that it would have been well received by your listeners.

My hot take: The pioneers were illegal immigrants.

No one gave them permission to come to Utah, which at the time was part of Mexico and already settled by multiple native tribes.

Is: “It’s not their right to be here.” May I ask what right your ancestors had to be here when they arrived?

I invite W&T to research the growing anti-inmigration protests in England. Why the protests? Why has the Starmer government become so unpopular?

Does England believe in government by the consent of the governed? Does the United States? What happens when government lies and disregards the will of the people?

Disciple, one possible answer to your question about anti-immigration protests can be found in Mosiah 29:27: “And if the time comes that the voice of the people doth choose iniquity, then is the time that the judgments of God will come upon you”. I can’t think of anything more deserving of the judgment of God than for the wealthiest countries in the world to collectively shut the door to those from poorer nations seeking to better their lives.