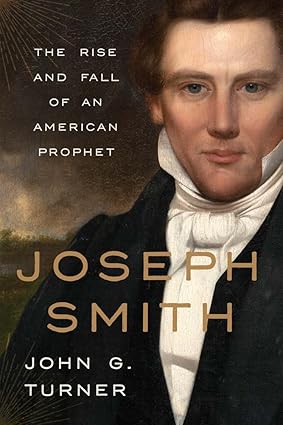

I’m almost finished with the new biography of Joseph Smith, John Turner’s Joseph Smith: The Rise and Fall of an American Prophet (Yale Univ. Press, 2025). I’ll do a post or two about it in coming weeks, and with a little luck some of you have started reading (or even finished?) the book already. But for now, let’s talk more generally about why some people read history and many others don’t, as well as why some Mormons read Mormon history and many others don’t. This is particularly relevant for an LDS discussion, given how prominent LDS historical claims are in the LDS testimony narrative. And let’s be honest: not that many people are particularly interested in history of any flavor, much less be inclined to spend money to buy and read history books. Does that matter?

Is reading history just a hobby that appeals to a few readers? Or does reading history convey some sort of worldly wisdom or historical perspective that makes life more meaningful or makes you better at your job or your relationships? For an LDS reader, what does reading Mormon history do for you as a Latter-day Saint, apart from making you better acquainted with the rather interesting story of Mormonism and some of its quirky details?

I’m just going to throw out a few claims (in bold below) and let readers follow up in the comments.

Familiarity with history provides perspective but it’s not a crystal ball. I think the most credible claim you can make for “why you should read history” is that it gives a person some broad perspective on how the world works. You can’t use it to predict who wins next year’s World Series, but it helps you put world events and maybe even personal events into perspective. Economic downturn feels like the end of the world? Nope, it’s just a cycle. Things get worse (often optimistically called “a correction”), then things get better. You think your country runs the world and that’s a permanent thing? Even if it does, it won’t be too long until a successor state displaces you. You think prophetic claims are inherently credible, because like who would lie or dissemble about something so important? There are a lot more wannabe prophets in any era than you think, and yes, historians have written about them. Most recently, try Heretics: Jesus Christ and the Other Sons of God (Mariner Books, 2024) by Catherine Nixey.

History is not guided by an unseen hand or a controlling force. It’s like the weather: it just happens. It’s hard to shake the conviction most of us pick up at some point that history is going somewhere or that some historical outcomes or developments are somehow preordained or absolutely bound to happen. Philosophically, it’s the difference between necessary events and contingent ones. The claim here is that it’s all contingent. It all could have happened differently. The idea that history “just happens” is especially hard to shake in religious history, even more so for one’s own denomination and particularly so for Mormonism. A comment in Sunday School class like “We’re really lucky the Mormon thing sort of caught on in early America” or “We’re really lucky a strong-willed and capable organizer like Brigham Young was around to pick up the pieces of shattered Nauvoo and lead the Saints to Utah” is likely to be met with a response, “Luck had nothing to do with it. God is in control.” As a matter of faith, yes. As a matter of history, basically no.

History doesn’t sit still: It needs to be rewritten every few years. This seems a little counterintuitive. You would think that a good historian using reliable historical sources could write a definitive history of this or that topic, and that would be the last word. Some might think, for example, that after Richard Bushman’s 2005 book Rough Stone Rolling, no additional Joseph Smith biographies would be needed. For a variety of reasons, that’s not the case. (1) New historical sources might come forth, requiring a reassessment of people or events. (2) New social, cultural, or scientific theories might emerge, causing historians to look at past events in a new light. (3) Different historians look at past events differently, because many historical events and issues remain open questions, subject to continuing investigation and dispute. And so forth.

I hope that context motivates you to read John Turner’s new biography of Joseph Smith, even if you have read one or more of the previous biographies. I’ll turn to that book in an upcoming post or two. In the meantime, think big.

- Is history worth reading, or is it just a hobby like golf or cross-stitch?

- Is Mormon history worth reading, or would you be better off using the time to remodel the basement or train for your next marathon?

- Here’s a big one: Do you think God intervenes in history? If so, does He do so once in a century, a few times each year, or on a daily basis?

.

I read some of “Rough Stone Rolling”, but really just enough to get a sense of what that era was like and what Joseph Smith was like in the first 20 years of his life.

Studying history is not for the faint of heart in part because the line between history and philosophy and ethics is really blurry at times and requires critical thinking skills our culture is losing to Candy Crush and other random dopamine-releasers.

The problem with studying Mormon history that the overwhelming theme of betrayal unleashed by accounts of the refugee saints forced to relocate across multiple states and the reckoning of how polygamy was the legalized betrayal of women and breaker of families. Even if your understanding of polygamy was more of the lines of an impersonal ritual sealing that functioned more like entry into a divine country club and less about the litany of financial/physical/emotional/spiritual abuses that supplying an extended nuclear family entailed, the betrayal fault lines between God and a man, God and a woman, and lastly man and wife are excavated to varying degrees.

An additional complication of studying Mormon history is that usually one starts because it is personal to them – it’s their family, their heritage they are putting under the microscope of examination. There is a 50-50 starting chance that it ends well when it is over that the individual will come to some conclusions that are meaningful to them. I would define that wrestle as “high risk, high reward” – and differing voices in leadership emphasize the “reward” part or the “risk” part in their counsel to the membership.

Have you ever heard a statement like this: “my testimony is not based on Church history so I’m not going to allow the Church’s messy history to damage my testimony” ? That’s a fair statement for some people but not for me. There are two main reasons why understanding Church history is so important to me:

1. if the Church has misrepresented the people and events involved in its history, can it be trusted in other areas?

2. if the core truth claims (the First Vision, translation of the BOM, translation of the BOA, revelation of the JST, restoration of the M Priesthood, formation of the temple ceremony, etc.) of the Church are tied to historical events and those events have been misrepresented, how can we have confidence in the truth claims themselves?

I’m kind of amazed at how forgiving some of you are towards the Church with respect to how it has handled and continues to handle its history. I just can not for the life of me understand how you can have confidence in its truth claims given the historical record that is quite easy to find. Maybe some of you have decided that history isn’t important because you are afraid what you might find out?

I believe I had previously avoided church history because I thought it was boring. And maybe it was uninteresting because the accounts I came across had so many relevant details omitted. Maybe I had a subconscious desire to avoid cognitive dissonance. But now it is clear to me how important understanding history is. I can engage with institutions that have unsavory events in their history, but it is deeply important to me that the institution be willing to acknowledge prior mistakes, mistakes of former leaders, and have an openness so that current mistakes can be rectified and systems improved. It is hard for me to trust an institution if I do not see this happening.

As an avid history reader, writer, and thinker, I believe that history reading is vital. We root both our personal and collective identities in history. To avoid being taken advantage of and acted upon in negative ways, and also to thrive in life and in group settings, it is incumbent upon us to craft narratives about ourselves and the environment around us. This always involves history. What happened and how it happened and what the relevant details are in the unraveling of a story. Having evidence and having a narrative means empowerment in your own life and within the environment around you.

I believe that each of us is in numerous ongoing battles throughout life whether we like it or not. History is important in navigating our way through those battles. In my own personal life, Mormonism and Mormon culture presents a massive battle for me. Other battles include politics, people in my career, and people in my more immediate environment. Studying Mormon history has been of utmost importance in helping me understand Mormonism, find justifications to distance myself from it, and to continue to navigate relationships with believing friends. Crafting narratives in my head that I buttress with historical facts that I learn and internalize after painstaking studying and reading has helped me keep at bay those who pressure me to participate in ways that I don’t feel comfortable participating in. On a larger scale, facts and narratives integrating those facts have emerged in Mormon history thinking that are so large, they’ve actually changed the trajectory of the church itself. We all know that the church is not by any means the same environment or culture that it was 50 years ago. Well, thank history for that. We need history, and really good history, now more than ever, especially in this age of Trump and alternative facts. Hold power to account. Don’t let power shape narratives that whitewash the past and wash away inconvenient truths. Don’t let shameless church leaders and apologists warp reality in order to manipulate believers to believe. Truth matters. But truth is hard to ascertain. That’s where history writing comes in.

josh h, excellent point. I always hear more knowledgeable members and apologists use the word “messy” to describe history and I absolutely detest that word. History is simply history. Describing it as messy is simply a bad excuse not to accept, dismiss, or downplay inconvenient facts.

Yes, history isn’t so much messy as it’s complicated and filled with contradictions and mysteries. A core problem is that it (at least official history) is written by the “winners,” the people in power who have their own agendas. Which is why it’s so essential for folks outside the power structure to probe, investigate, and continually seek new understanding. When individuals and institutions use a particular historical perspective to promote faith (or, in the case of politicians, to promote patriotism) it’s practically guaranteed that history gets twisted in unfortunate and dangerous ways. You can bet that somebody’s going to be judged as an outsider and/or inferior and unworthy.

.

We haven’t taught church history in church (RS, Priesthood, or SS) for years. As a result, many members don’t know it. They don’t even know what they don’t know, and if they are presented with it, they deny it. At least that’s what I’ve seen in my ward. People may get some history at the Institute or BYU religion classes, but it’s pretty sanitized. You have to read and investigate on your own, and then you run the risk of being called lazy.

Personally, I think reading history in general is very important, but there’s a season for everything we do in life. I couldn’t bring myself to read WW2 history until the last few years because it was mostly horrible and also I don’t enjoy war narratives in general–I prefer personal stuff. But now I’ve devoured like twenty Holocaust books and been all over the sites where major WW2 events happened. And I can’t stop. I’m impressed that Holocaust survivors immediately demanded that concentration camp sites like Auschwitz be maintained so that people would know what happened there.

As to Church history, it’s certainly true that the Church doesn’t teach church history and hasn’t for a long time. Reading Truman Madsen always seemed like reading a Superman comic book with Joseph Smith in the protagonist role. It was so obviously white-washed it strained credulity. All history has a perspective, but also let’s get real with some of this stuff. Ditto the Saints book. I know there are people who think it’s “touching” or “moving” to hear these very maudlin accounts that just don’t feel like real people, but it’s not for me.

As a country we are very seriously at risk of introducing bizarro history into our education system. There are many schools now using Praeger U videos which are just dishonest in the rosy conservative patriotism they portray. They literally have John Adams quoting Ben Shapiro (!) that “facts don’t care about your feelings.” Like, what the actual hell are we doing here? It’s completely insane. It’s not that far off the rosy picture that so-called church historical narratives paint, though. If that’s what we mean by Mormon history, no thanks.

I read Rough Stone Rolling, and personally I found it pretty dull. Mormon Enigma was better, but also dragged on a bit. I think on some level since I have no Mormon ancestry, these tales just aren’t from an era I find that interesting. Well, that’s not entirely true as I love reading Jane Austen who published 15 years before the founding of the church. But I’ve also never gotten interested in reading about the Civil War either. We all have our time periods we find more interesting I guess.

I agree with prior commenters in that History is messy ( and or complicated). History is also open to interpretation and when trying to understand history on must try to avoid anachronistic thinking, meaning avoiding imposing your own values on people in earlier periods of time that did not share those same values as you do. One way of reading history is to read multiple books ar articles about the same events. In every case, in my experience, each author will include pieces of information that others may not choose to include and thus for me enriches the history. I am currently reading John G.Turner’s biography about Joseph Smith and am comparing his work to Richard Bushman’s and Fawn Brodies work to how each compared to each others interpretations of Joseph’s life and work.

Raymond: I’d love to read a write up from someone who would like to compile a comparison of the different approaches to a JS biography. I mean, really anyone could write that, and probably ChatGPT could do a decent job of it as well.

“To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain always a child.” The quote is attributed to Cicero, and, whether it is universally true or not, the quote has always rung true to me.

Unvarnished Mormon history has always felt to me like some sort of big secret those “in the know” were keeping, and, at least at first, it felt sorta cool knowing things that were apparently taboo to reveal to the membership at large. Occasionally, you’d come across someone who would drop hints that they were aware of a particular issue, and you might test the waters to see if they were a “safe” person with whom to discuss the issue in more detail.

In the last year, in my ward we had a whole lesson on multiple versions of the First Vision which forced some very orthodox people to wrestle uncomfortably with the facts that they don’t like. The entire Church will also be discussing D&C section 138 in Sunday School later this year and have to come face to face with some very uncomfortable language about polygamy.

While this may all be agonizingly slow to many, it’s still significant progress in so far as it is exposing Latter-day Saints to some of the weirdness of Mormon history (which I realize may be damning with faint praise).

My first brush w Mormon History was when I picked up Joseph Fielding Smith’s “Essentials in Church History”. Having been raised in the church by an active mother, I knew the very basics of gospel teaching and how those basics had been originated, mostly by Jos. Smith, but there had been little to no “history” as such taught in my Primary and Sunday School classes to that point, so I found that book highly informative. I laid it down thinking that Now I Knew the church. Of course it didn’t occur to me then that the book was so completely one-sided as to be almost worthless as a true historical document, but I realized that a little study of the basics, and how they originated, is a very good thing.

So, in answer to the OP’s question: I think that time spent studying church history is important both for the TBM and the agnostic member – perhaps for different reasons, but those different reasons are still necessary in each case to help move the discussion forward.

Richard Bushman’s “Joseph Smith and the Beginnings of Mormonism” is a great place to jump into church history, IMO.

A certain amount of historical knowledge, in general, is really important. My daughter and I had a discussion recently where I expressed frustration with how we allow people with such a small amount of historical knowledge (as well as a lack of elementary understanding in certain fields like economics, science, etc.) to vote. While the discussion was focused on today’s political situation in the US (yes, I think a lot of MAGA people–including the MAGA man himself, Trump–are very lacking in historical knowledge), I have encountered plenty of ill-informed people on the left as well. I have no solution to offer, but it does seem to me like people would vote differently–and better–than they do if they had just a little more historical perspective to work with.

It’s been awhile since I read Rough Stone Rolling, but I do remember enjoying reading Bushman’s discussion at the beginning of his book regarding how writing a history book about a religion–any religion–is particularly fraught. You have supernatural claims about things that purportedly happened which typically only adherents to the religion accept as real while outside observers reject due to lack of sufficient evidence. The author has to deal with that in some way, and Bushman lets his readers know how he chose to deal with it in RSR.

I agree with @Hawkgrrrl that Rough Stone Rolling is a long book written in a pretty dry way. That’s kind of the beauty of it, though, too. Bushman tried his best to be objective and present things academically, including both a faithful and skeptical perspective on some issues. It’s a book that both the believer and the non-believer can agree is a reasonable source to go to for information. However, I do wish that there were a shorter, easier to read book about Joseph Smith and the beginnings of the Church. Rough Stone Rolling is hard for a lot of people to get through. When my kids were in high school, we read Rough Stone Rolling together as a family. My wife insisted on family gospel study, but allowed each family member to take turns picking the books, so I picked Rough Stone Rolling when it was my turn to pick. The information in Rough Stone Rolling is great, but it is in a form that is difficult for high school kids (and a lot of adults, too) to get through. I just didn’t think there was really any other book I could use at the time, though, to make sure my kids were informed about JS and Church origins. The initial Saints books were released while my kids were in high school. Those are easy for high school students to read–and my kids probably would have enjoyed reading them–but they simply don’t contain the information these kids need to know.

I’m on the record as saying that the biggest problem the Church is facing right now is its insistence on prophetic infallibility. The Church was slow to allow blacks to enter the temple because of prophetic infallibility. The Church was slow to stop the practice of polygamy and still hasn’t refuted the practice because of prophetic infallibility. The Church is currently dragging its feet on LGBTQ and women’s issues because of prophetic infallibility.

I think the faster cure for embracing prophetic fallibility is for the average Church member to have a better understanding of Church history, including a number of cases where prophets have erred in the past (I mean, we even have clearly documented cases of this in the Bible–it’s not just “modern day prophets” that have erred). I’m 100% certain that most members are unaware of the numerous instances where prophets did/said/wrote the wrong thing in big ways over the years. As a result, the average faithful member just accepts the official Church position as infallible. If they really understood how unreliable the Q15 has been over the years, I think a lot of them would demand faster change on important issues.

Does God intervene in history? I have absolutely no idea whatsoever. I’d love to know the answer, though! The only thing I have to go on right now is the sense that very occasionally I feel inspired with some ideas that don’t feel like originated from my brain. If those thoughts actually come from God, then I would assume that He’s at least intervening in other people’s lives in a similar way–and perhaps in more profound ways. However, I’m not really certain that the “inspiration” I think I very occasionally receive isn’t actually just originating from inside my own brain without any Divine intervention whatsoever. It’s entirely possible that God isn’t intervening in people’s lives at all (or even that He exists in the first place).

While I agree that “history happens” I think one should be cautious about viewing life as just a random cascade of events. Individual and collective choices do matter and the right (or wrong) choices by the right (or wrong) people do change history.

Brigham Young was the greatest colonizer in American history. His accomplishment wasn’t accidental. He did something he was uniquely qualified to do. His achievement all the more impressive given how consequentially his predecessor had failed!

Same for American independence. The American revolution succeeded for substantive reasons, not just because it was lucky or blessed by God. America was fortunate to have leaders who possessed the right ideas – ideas that worked. The wrong ideas would have resulted in a failed revolution.

History is greatly polluted by bias and the “victory” narrative – that the end was preordained from the beginning. It behooves the student of history to filter out the bias and discern the factors of consequence. Luck can be a factor. But the human element, and intelligence or lack thereof matters to the fate of nations and communities.

History is important for anyone who wants to really understand the world they live in. Mormon history is important for anyone, member or otherwise, who wants to really understand the religion. At the top of my reading list right now is Matt Harris’s Second Class Saints. I am interested in understanding how the mistakes of history get made (I’m unequivocally in the camp that the priesthood ban was human error), how they get corrected, how human dynamics of an organization help and/or hinder getting to such an objective.

Much of the membership of the LDS church isn’t prepared for the questions about human frailty and prophetic fallibility that studying church history raises. I think it’s the primary reason why the church hasn’t been keen to publicize the gospel topics essays. But this is a problem partly of the church’s own creation, thanks to serving generations of members bland, correlated, watered down curricula. We would be a better church for it if we could have adult discussions about the thorny questions raised by our history, so I do believe members should be studying church history.

I’m in the same camp as josh h.

Unless my dead parents visit me like Yoda and Obi-Wan to impart the “truth,” I refuse to believe in Jared’s bro, 3 Nephi 11, Moses returning to Ohio in 1836, the Seagull miracle, Nelson’s plane crash etc.

At least when I watch movies based on a true story, I can get the lowdown afterwards on wikipedia.

Yes, I think that history is worth reading. I recently finished Saints Vol 4 and have found all of the Saints books to be worthwhile. Everyone should read them.