Let’s get the ball rolling with a short piece at Bart Ehrman’s blog titled “How Many Books in the New Testament Were Forged?” Now the word “forged” seems fairly harsh for biblical books that millions of believers accept and affirm as inspired scriptural texts. Scholars often use the term “pseudepigraphical” rather than forged, but both are used to refer to texts that claim to be written by a famous ancient author but were, in fact, written by someone else. There are, in fact, several related ideas that come into the discussion, as noted in the Ehrman post:

- An anonymous text makes no claim of authorship, although later readers may posit a particular author. The four gospels, for example, are anonymous texts, with the later attribution of authorship to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John (rejected by most scholars) coming much later.

- A homonymous text is one written in the author’s name, but that name is shared by a more famous ancient person and later readers falsely attribute the text to that more famous ancient person. The text of Revelation, for example, claims authorship by “John” and identifies the author’s location as Patmos, a Greek island, so the author is often referred to as “John of Patmos.” The text itself is not a forgery in the sense that the writer claimed to be John the Apostle. Later readers, however, attributed the text to John the Apostle.

- A pseudepigraphical text is one that falsely claims to be written by a famous or notable author when, if fact, it is written by some other person. These are the texts to which the term “forgery” is properly applied, recognizing of course that such disputed authorship claims are inherently probable rather than certain. Of the fourteen New Testament letters often attributed to Paul, seven are undisputed (Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, and Philemon), while the other seven (2 Thessalonians, Ephesians, Colossians, 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus, and Hebrews) are questionable or very likely not written by Paul. Hebrews is sort of a special case because the text does not explicitly claim Pauline authorship.

- An authentic text (Ehrman uses the term orthonymous) is one that makes a claim to authorship and was actually written by that claimed author.

With those distinctions in mind, let’s take a candid look at the New Testament, then ask if and why the question of authorship matters.

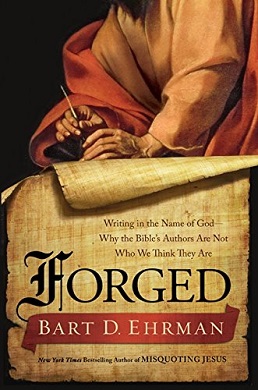

Here’s the big reveal: Only seven of the New Testament’s 27 books are authentic in the sense that they are written by the text’s claimed author. These would be the seven undisputed letters of Paul. If you accept that the Deutero-Pauline letters are authentic, then you can bump that number up to ten or thirteen. The rest are anonymous (with later false attributions), homonymous (John of Patmos did not claim to be John the Apostle), or pseudepigraphical (i.e., forgeries, such as 1 Timothy, explicitly claiming Pauline authorship when someone else wrote it). These are roughly the results Ehrman gives at the end of his short post. For a longer discussion, read his book Forged: Writing in the Name of God — Why the Bible’s Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are (HarperOne, 2012).

Why would an early author write a forgery? To get his or her ideas read and taken seriously. If you were a first-century Christian nobody named Demetrius who had some interesting thoughts to share on this or that Christian belief or doctrine, writing a Letter from Demetrius won’t get much or any attention from other Christians. But if you (Demetrius) write a supposed late letter of Paul to the Thessalonians (3 Thess.) and slip it into a collection of Paul’s letters or put a copy on the shelf of this or that collection of Christian texts, some Christians will read it. It may become popular and accepted as an authentic Pauline letter. This is exactly what most scholars think about 2 Thessalonians.

Why did early Christians falsely attribute some texts to early Christian writers? To grant credibility to a text they liked or a text that had become widely accepted. An anonymous text written in the late 1st century purporting to narrate the life and teachings of Jesus has questionable standing. The recounted events and teachings might or might not relate things Jesus actually did or said, depending on how carefully oral traditions and perhaps early written texts (say a collection of purported sayings of Jesus) preserved those events and teachings. But if that text was written by say Matthew, one of the Twelve identified in the text, who was possibly a contemporary eyewitness to what is conveyed in the text, the text becomes much more credible. In fact, when the New Testament canon was formulated in later centuries, claimed apostolic authorship or a close connection to an apostle was almost a necessary requirement for consideration.

Why do some modern Christian denominations continue to affirm traditional authorship ascriptions despite scholarly opinion to the contrary? It’s not just opinion, of course, there is a lot of textual evidence to support those views. Continuing to affirm traditional authorship serves the same purpose as the original false attributions did, by lending credibility to the texts. The general sense seems to be: Why open a can of worms by questioning traditional authorship? Do that, and what else will members of the congregation or denomination start questioning?

Is affirming false authorship a problem? Well, that depends. If you are a Christian sincerely trying to puzzle out what Paul is saying in Galatians by appealing to passages in Ephesians or Colossians, yes that’s a problem if Paul didn’t write Ephesians or Colossians. They are evidence about what some other early Christians were thinking, but not of what Paul thought. Actual writers were aware of the possibility of others writing in their name and *they* were not happy about it, so maybe we shouldn’t be happy about it either. I think some people just don’t want to be bamboozled by some second-century forgery, even if that forger had sincere motives (“Paul would have agreed with me,” or “these are important points I want people to take seriously”). On the other hand, some people just don’t care who actually wrote New Testament texts. “Hey, it’s in my Bible, that’s all I need to know” is certainly a common view.

What’s the LDS angle? You won’t get any of the above discussion or conclusions in correlated LDS sources. Don’t expect an LDS manual to tell you Paul didn’t write Hebrews. You won’t get an LDS Institute teacher questioning John the Apostle’s authorship of Revelation, unless they (1) have read outside LDS sources and accepted scholarly conclusions, and (2) they trust you enough to share that view with you in a private conversation. The LDS rule is this: Thou shalt not question traditional biblical authorship in any public teaching or statement.

I honestly don’t know how much of the scholarship on biblical authorship LDS religion teachers are familiar with or how much of it they accept. I imagine as you move down the hierarchy from BYU faculty to full-time Seminary and Institute teachers to part-time S&I teachers to your own ward’s adult Sunday School teacher you will find progressively less awareness of scholarly views.

What about LDS leadership, the apostles and other GAs that are so frequently quoted in LDS manuals? And it is only LDS leaders who are quoted, which is a little odd. BYU and other LDS scholars of unquestioned loyalty do write books on the New Testament, for example, but you almost never see their discussions or explanations quoted in LDS curriculum materials. Instead, LDS apostles, with little or no education or training in biblical studies, are the ones always quoted. Their statements uniformly endorse traditional authorship. Once in a while an LDS leader might use the phrase “the author of Hebrews,” letting informed readers know he is aware Paul was not really that author, but that’s about it.

This is a big topic but a very relevant one for most readers. It is certainly relevant for scholars who study these texts. I haven’t even turned to applying the idea of forgery to LDS texts and scriptures, which of course would be a whole ‘nother discussion. I’ll save that for another post.

So what do you think?

- Does it matter to you, for example, whether Paul wrote the pastoral letters (1 and 2 Timothy and Titus) or whether it was some later Christian writer with something to say about Christian leadership who decided to put those ideas into the mouth of Paul?

- Does anonymous authorship of the four gospels bother you? Or is it fine to just say, “Well, some early Christian wrote it and he or she seems to know what they are talking about.” Even critical scholars start with the text of the gospels as potentially accurate accounts of the life and teachings of Jesus — there is nowhere else to start, really.

- Should LDS curriculum materials and public teaching be more willing to entertain or at least mention scholarly questions about authorship? You will sometimes find a “some scholars question the authorship of X” statement in LDS materials, followed by an endorsement of traditional authorship. But you won’t find a detailed discussion of those views or a footnote to an actual source.

- What do you do if you teach an LDS class on the Old or New Testament? Do you bring up authorship? If you do, are you honest about it? Do you mention scholarly views? I’ve posted about the ethics of teaching before, so I won’t repeat that discussion here, but it is relevant.

- How about the frequent directives to teach only what is in the manual? That can be a real problem. If you are a teacher, do you ever use other LDS sources or other scholarly sources to supplement your teaching?

.

ask Adam Clarke

The problem with LDS attribution is that LDS revelations hardwire in the misattributions as legitimate. The Book of Mormon directly attributes the Book of Revelation to John the “Apostle of the Lamb” in 1 Nephi 14, not to John of Patmos, who was a different guy. Same problem in D&C 77.

I think authorship in any context lends credibility and authority. For example, take the 4 gospels and remove any mention of Jesus and have his sayings stand on their own independent of his. They would be immediately viewed as nice sayings to live by. Yet, with Jesus as the author, all the sudden, those words become more than just sayings. Look at how much we elevate the words of Joseph Smith just because they came from Joseph Smith and all that we believe he is. It adds a significant amount of rhetorical weight and authority behind them that wouldn’t be there otherwise. In the end, I guess it depends on how you view, relate to and use the texts. I believe that most humans tend to filter content first by author trust metrics, then by the content itself. Doing it that way reduces a lot of cognitive load.

“Even critical scholars start with the text of the gospels as potentially accurate accounts of the life and teachings of Jesus — there is nowhere else to start, really.”

This sums up my experience with Reza Aslan’s Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth, which I listened to on audio a few years back. I enjoyed it. It seemed compelling scholarship. And unmistakably it leaned heavily on the Gospels for laying out a plausible account of a historical Jesus, while acknowledging the anonymous authorship.

Speaking as an agnostic, I’m no longer bothered by anonymous authorship. Furthermore, I like how the canonical gospels each have distinctive differences and styles, offering contrasting takes. I think that’s useful, allows for acknowledging each text’s limitations and strengths, and doesn’t require all the mental wrenching needed to pretend the texts are in total harmony and free of contradiction.

It’s when we go all in on one source, or on one interpretation of a set of sources, and then attempt to say, discussion is over—that’s when we get ourselves and our institutions in to trouble.

Reminds me of the time a couple of years ago when a Jeopardy clue made reference to a Pauline epistle and the correct response was “Hebrews”. A certain element of the fanbase went bonkers over the “false attribution.” But the King James Version is the authoritative Bible in the Jeopardy universe, and serious fans know that. It attributes Hebrews to Paul, and that settles it. (The KJV rule probably dates back to the Art Fleming era, so don’t be blaming Ken for this.)

I believe this matters a great deal. Studying the Hebrew Bible and NT using a good study bible, is what started my deconstruction.

Our theology has a strong basis in the literal interpretation of the Hebrew Bible in particular, so if that goes, polygamy crumbles, racism crumbles, patriarchy crumbles, etc etc,

I wonder if the words and tenor of the OP don’t inadvertently misrepresent things somewhat. For example: “Here’s the big reveal: Only seven of the New Testament’s 27 books are authentic in the sense that they are written by the text’s claimed author. These would be the seven undisputed letters of Paul.” This makes it sound like we can throw away 20 of the 27 books because all of the 20 are not authentic, and therefore are likely forgeries, as suggested in the post’s title. The four gospels are anonymous, as we’re told in in the post, but that does not in any way mean that they are forgeries or that they are not authentic. John’s three epistles are also anonymous, but may be perfectly authentic. Similarly, Revelation only claims that it was written by John; the text never claims to the same person as the disciple John. Perhaps it matters how we define forgery and authentic. We can say that Gustave Eiffel built the Eiffel Tower, but in fact he built nothing; he had people who actually built it. We call the Eiffel Tower an authentic Eiffel work. We also know that St Thomas Aquinas probably never wrote any part of the Summa Theological: he dictated it to scribes, but we still say that Aquinas wrote it. An anonymous work can be perfectly authentic, can’t it? The gospels simply tell a story, from different perspectives, but anonymity in authorship does not equate to forgery or inauthentic. Early councils considered all the questions of authorship and provenance and they canonized the 27 books. They looked at a lot of other texts, many of which may have been perfectly authentic by this post’s definition (that is, they were written by the person who claimed to have written it), but they were not canonized, usually because their teachings were wrong: they were authentic by the post’s definition, but in content they were erred. I think that the contents of the text trumps the attribution. A name helps enormously, but need not be divine; similarly, the chapter and verse divisions are wholly non-scriptural (and are actually relatively new), but they are extremely useful. So I have no problem with the names put on the gospels or on the Johannine epistles, because it helps us keep track of things, but it doesn’t have to be an article of my faith that Mark wrote Mark, or that Matthew wrote Matthew..

I’ve understood that the gospels were, at first, oral lore and not written lore. I’ve especially understood that the gospel of Mark was likely “performed” at gatherings and may have been initially handed down as an oral tradition. Is this true? Does it impact either authenticity or authorship?

“What do you do if you teach an LDS class on the Old or New Testament?”

As an adult Sunday School Teacher (Gospel Doctrine, we hardly knew ye), I brought the issue up during the New Testament year when we got to the epistles as well as including a note about authorship in my introduction to every epistle. There was a bit of wrestling within the class with what disputed authorship might mean for us in understanding the New Testament, but somewhat surprisingly it didn’t prove to be all that divisive a subject. We were there to take what we could from the scriptures to help us live better, more fulfilling lives, not to attend New Testament Textual Criticism 101

One other thing: I pointed out to the class that in the absence of a revelation binding on the Church (and yes I pointed out the John the Apostle verse from the Doctrine and Covenants but even then I noted that there could have been multiple apostles named John), we were free to make our own conclusions about authorship. Sure, many LDS leaders assume that the names on the various books of the Bible are authoritative, but none that I know of have suggested that that assumption is based on anything other than tradition (i.e., no angel came down and told them Peter wrote the epistles that bear his name).

To whether this kind of discourse is helpful for Latter-day Saints, I think the “problem” with going down this road is what LoudlySublime found. It often leads to a deconstruction of faith and what’s left over doesn’t fit neatly within the bounds of mainstream Latter-day Saint practice. And the problem of simply ignoring questions of authorship is that sooner or later a certain percentage of the Church’s congregation is going to find out this stuff anyway so long as the Internet is around [cue EMP going off in the upper atmosphere].

I don’t think the average gospel doctrine teacher (who doesn’t spend time on Mormon blogs) would appreciate having to introduce issues of authorship during a lesson. They already have two weeks of material to get through that no one has actually read, don’t really want to be challenged too much, but know enough to keep a discussion going for 40 minutes. Sometimes these discussions can be quite productive, sometimes not. I’m saying this is good or bad, it’s just the way it is.

I would like to see more critical scholarship brought into the CES system. Unfortunately, theological training does not appear to be a requirement to get a job as a seminary teacher, institute teacher, or religion professor at the byus. In fact, it seems to be actively discouraged. This is quite sad and self-defeating imo. If you don’t want kids to google answers to their questions (which the Church doesn’t), than it doesn’t make sense to hire a seminary teacher who isn’t equipped to answer them, beyond pulling out a quote from RMN.

Proudly PIMO, I had the adult Sunday School Teacher calling during the last cycle for OT/NT. I tried to emphasize the Bible as literature, including allegory (i.e. Jonah). As one peruses the Come Follow Me materials, it is obvious that the in-house curriculum writers love to steer the lesson towards obedience and temples. I made it a point to regularly have other types of discussions i.e. Renlund’s talk from October 2020 about mercy.

I moved to a different ward and thought BOM lessons would be OK if I could, as a learner/participant, glean lessons like I could from Harry Potter or Star Wars, but too many of us still believe that the golden plates actually did lay hidden deep in a mountainside.

This year I would rather skip Sunday School and head to 7-11 for a hot dog while pondering the psalms of Bon Jovi.

” Only seven of the New Testament’s 27 books are authentic in the sense that they are written by the text’s claimed author. These would be the seven undisputed letters of Paul.”

Nina Livesey says they are probably fake too. Excuse me, “epistolary fiction”:

That means Paul is just a character in Acts, maybe a Marcionite creation.

[Note from Dave B.: you can find Nina Livesey videos about Paul by searching at YouTube]

Thanks for the comments, everyone.

Mike S, yes that’s an issue. My reply, I think, is that (as noted by other commenters) the Book of Mormon text assumes traditional authorship in the same way modern GAs assume traditional authorship.

chrisdrobison, very on point comments.

Jake C, there’s a lot of discussion to be had about four anonymous gospel writers, each of whom give us a somewhat different Jesus. What I don’t like is the LDS curriculum approach of harmonization, just smush all four together, giving us a homogenized Jesus. That does not do justice to any single gospel and works against any serious engagement with any single gospel on its own terms.

lastlemming, you have destroyed my testimony of Jeopardy.

Georgis, I think I did cover a lot of what you insightfully noted in my OP. I quite explicitly distinguish between anonymous, homonymous, pseudepigraphical, and orthonymous (what I call “authentic”) texts.

stephenchardy, yes I have heard Mark was likely delivered read out loud in those early house church meetings — necessarily so in some form as most early Christians, like most inhabitants of the Roman Empire, were illiterate. Before Mark, it was apparently all just oral storytelling, an oral tradition. That’s a good point that repeated storytelling likely modified (embellished?) the pre-Markan oral tradition over time, before the writer of Mark used selections from that oral tradition to create his written narrative.

Not a Cougar, thanks for sharing your enlightened experience as a GD teacher. I’m afraid most adult LDS could write a book called “Lies My LDS Sunday School Teacher Told Me.” But there would be one or two teachers in that book who took a better approach.

mat, I agree. As a teacher, you have to choose you battles and avoid an approach that generates lots of heat and little light.

chet, you’re a Sunday School Runaway.

Dave B.: “there’s a lot of discussion to be had about four anonymous gospel writers, each of whom give us a somewhat different Jesus”

More like redacteurs. The text of Matthew and Luke both incorporate–i.e. copy, more or less wholesale–the text of Mark, plus a hypothesized sayings (of Jesus) source, the fabled Q. We know from the Marcionites that there was another version of Luke floating around, and textual analysis suggests that canonical Luke came later. John may have begun life as the “seven signs” gospel, and been rewritten in order to take into account failed prophecy. If Morton Smith is to believed (I am skeptical), there was also a Secret Mark that has priority over canonical Mark. Anyway, the picture that emerges is not of four independent witnesses, but something far more complex.

I am familiar with the arguments and counter-arguments for the authorship of the books of the NewTestament as well as the same debates over the authorship of the books in the Old Testament. I find much of value in the bible. One of the beauties of the Bible, if we allow ourselves the vision to see it, is the diversity of voices present in scripture and the wisdom that cam be found there if we could but look for it.

“I don’t know who wrote Ecclesiastes but I know who didn’t write it and that’s Solomon.” Prof. Shaye Cohen

My orthodox Mormon opinion, back in the day, was more along the lines of, I know the Bible is faulty to begin with so I’ll take these text and learn them but when they contradict the teachings of the church, I’ll go with the church.

So Epistles being written by someone else wasn’t an issue for me and also if JFS is reading Peter and getting section 138, then Peter must be true.

Restorationism is a curious thing. Deconstructing the New Testament takes that curiosity to a whole new level – reductionism really. Not sure that it gets us back to restoring the oral narratives of the first century church preserved in Mark and the Book of Acts, and Paul’s epistles.

“And thus we see” the importance of the Book of Mormon standing as a witness of the Bible.

Sorry Jack,

Using the Book of Mormon to defend the absolute historicity of the Biblical narrative is about as useful as bringing a pocket knife to a gun fight.

I simply assume that the NT contains a number of forgeries. From its inception, Christianity was replete with figures who wanted to move the movement in one direction or another. Of course people would write things that they would claim to be from earlier apostles and leaders. We know there were forgers later on, that means there were forgers earlier on as well. Heck, the writers of the NT accused other Christians of being false prophets. There were forgers of Isaiah and other Old Testament books. Forgery and holy texts simply go hand in hand. We know that good forgers are capable of duping large numbers of people to believe them. Mormonism is a massive case in point. Joseph Smith was a forger extraordinaire and look at what he managed to create. There are even extremely bright minds educated in the highest universities defending his nonsensical claims. What I’m more interested in is in nailing down the process of how forgery took place. Something that is very hard to do. But something I think we can do to some extent with strong educated guesses.

“How about the frequent directives to teach only what is in the manual?”

Having been an Elder’s Quorum teacher on a couple of occasions, I was told several times by Sunday School presidencies to teach the manual. I always gave them the middle finger in my mind. I truly hated, I mean hated, people telling me that.

Jack – Star Trek does not prove that teleportation actually works.