I ran across a short story that originated on that social media site back when it was called Twitter. It’s a conversation between God and a person asking him questions. It parallels the ideas I brought up in my post Mirror, Mirror on the Church Wall, and I wanted to revisit this in a new format.

The story explores the question: Why do bad things happen to good people? First, we have to acknowledge the premise of that question. It assumes that bad things shouldn’t happen to good people, that someone (God) should prevent bad things from happening to good people. Why do we make this assumption? (Or do you not make this assumption?) I posit that the assumption comes from humanity’s craving for justice and control. We want to control what happens to us, so by doing good, we deserve good things. Also justice – it offends something deep in humanity to see a bad person getting good things, and a good person being afflicted with bad things.

The question also assumes that we can define ‘good’ and ‘bad’. I’m going to sidestep that question for this post.

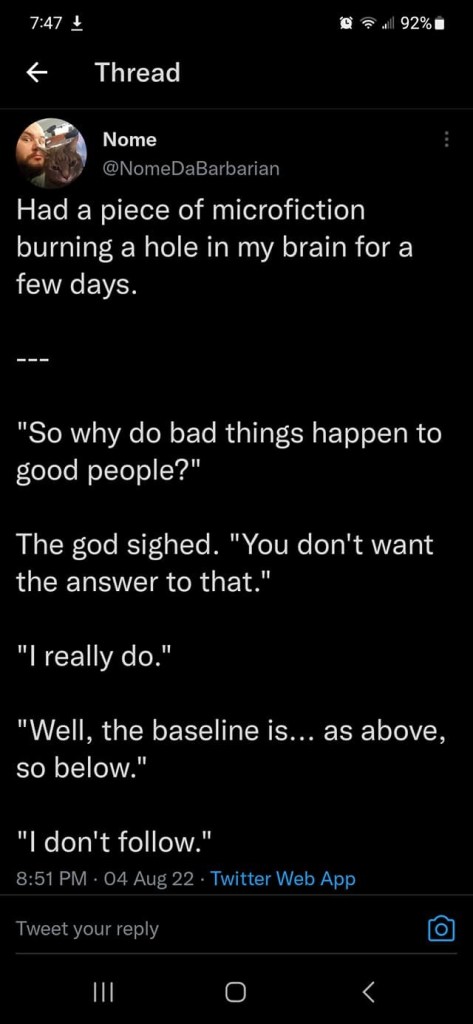

Here’s the first screenshot of the Twitter post, written by NomeDaBarbarian, and then I’m going to type in the rest to save space.

“At certain points, belief has a quality like … like momentum, or inertia. The faith that exists now isn’t much at all like it was when I began. different things matter to believers, and different things move them.” He waved his hand. “I was an Ancient near Eastern War God. The ‘Lord of Hosts’ doesn’t mean I’m in charge of restaurant staff, after all. I was good at that, you know? I killed Tehon, used her body to make the continents. After that, it was just the occasional fight against Ba’al or Marduk. That was my wheelhouse. I could handle that. But then folks started saying I had power outside my soil. that I was actually The Most High – Christ, El Elyon was pissed when he heard about that.”

“… you say Christ as an invective?”

“The irony isn’t lost on me, chief.”

“But what does that have to do w-”

“With ‘as above, so below’? I’m getting to it, don’t worry.” He sipped from the cup in front of him. “Belief is a tricky thing. Folks started believing different things about me. Omnipotence. Omnipresence. Omniscience. Eventually … well eventually it becomes part of the job description. Suddenly a minor war god from rural Mesopotamia gets promoted to Most High, old allies and enemies get demoted to Angels – that makes for some awkward Christmas parties by the way – and everything changes.”

“What people believe about you … changes you?”

“Including when they believe you’re unchanging, yes. Don’t think about that one too long, you’ll get a nosebleed. Just accept that there’s no obligation for reality to be realistic, or logical, or self-consistent.”

“That’s … surprisingly easy for me to accept. all things considered.”

“Yeah, you’re from … 2022, right? That’s a good year for realizing nothing that you thought was stable is based on anything firm.”

“Yeah. Yeah. That’s … yeah.”

“But that brings me back to your question. To answer it, I’ve got to ask you – define a good person.”

He paused for a second. “Someone who … helps people? Someone who takes accountability for their actions. Who doesn’t hurt other people, who cares about the world, wants to make it better?”

“That’s good. A bit vague. When I started, a good person obeyed the laws of hospitality, made burnt offerings, and respected property rights people. People who did that, within the very specific physical boundaries I was responsible for? I could do my best to stop bad things from happening to them.” He looked wistful for a moment – and more than a little sad. “There’s a town in South Carolina. It’s got two First Baptist churches, across the street from each other. A legacy of segregation – one used to be the white church, one the Black. Both are integrated now. Both congregations believe that everyone else in the world, up to and including the other church across the street, is wrong, deceived by Satan, and damned to hell for their wickedness. That they alone are My Elect.” He made a broad ‘what can you do?’ gesture with his hands. “I started as a war God. I’ve seen a lot, you know? Done plenty of terrible things, myself. But…”

He shook his head. ‘When you’re responsible for so much, the scales can’t balance. It’s literally impossible for me to be on both sides of a war, for instance – but I have been. It is not possible for me to decide to fix that, because – as above, so below. I am what you, writ large, believe I am. You believe – not you, personally, but all of you … I swear, English never should have abandoned ‘thou’. Anyway.” He made a wiping – away motion with one hand. “You believe that some people must suffer. That it is somehow natural for some people to starve, or to waste away, or to freeze or boil. That a certain vague number of people are acceptable losses.”

He spread his hands. “And that I am the enforcer of that. That I will, with my perfect knowledge, winnow out the deserving and protect them from harm. For a thousand different and mutually exclusive definitions of deserving. Come down to it, like so many problems, it’s a problem of scale.”

“So it’s just … hopeless?”

The smile that came to his face then was a comfortable one. Well-worn. “No. No. Not hopeless. It’s just broken. Things break, sometimes.”

“So how does it get fixed?”

Genuine warmth in that smile, now. “I know it doesn’t help you sleep at night, but I honestly love that about you. I love that your first instinct with a broken thing is to try to fix it.” He leaned forward, taking the man’s hands in his own. “As above, so below. You – all of you – have the power. You have something that I don’t – a choice. If you choose to believe that suffering is natural, it will be. if you choose to believe that the world is harsh, it will be. But on the other hand …”

“If you wish, you can reject that premise. You can choose not to accept hunger, illness, poverty, deprivation. You can choose for the world to be a place without suffering. And because you are the ones with that power, it will matter that you’ve chosen that.”

The man shook his head. “We can’t even agree on the basic facts of what’s already happened, how can we possibly all choose a future like that?”

The God lifted a hand to the man’s cheek. “If it makes a difference, I believe in you. I don’t know how – but I’ve got Faith.”

“That’s … comforting. But I don’t know if that’s useful advice.”

“You didn’t ask for useful advice. You asked why bad things happen to good people.”

“… fair.”

The God let his hands drop, and grinned. “As far as useful? Next time, look both ways.”

“Next time?-

“CLEAR!’

His eyes jerked open, taking in the sight of the paramedic – and over her shoulder, the driver, tears streaming down his face.

“You have a terrible sense of humor,” he rasped.

“I can respect that.”

END STORY

The aspect of this story that really made me think was the way it pushed our unrealistic expectations of God back onto us. In this story, God doesn’t try to rationalize why bad things happen; he accepts no responsibility to make good things happen.

Why do we teach that God cares about human life? The Bible is full of wars, slaughter, and suffering. Prophet don’t typically reveal anything that contributes to health. Leviticus has some good, basic hygiene rules. But the God who revealed the precise measurements of the ark to Noah didn’t reveal ways to heal wounds, prevent illness, or give mothers and babies a better chance of surviving childbirth.

Jesus cared about healing the sick and afflicted. We got three years of compassionate preaching and miracles that helped people. But Christianity didn’t become a worldwide religion based on compassion and healing. War and forced conversion of entire populations spread Christianity.

So why do we teach that God wants to prevent suffering? Or that he respects free will? I posit that it’s because that’s the kind of God that we believe is worthy of worship.

Currently, a loud and powerful coalition of Christians have re-emphasized God’s callous Biblical view of human happiness. The story I quoted above says that God is who we say he is. So … God is a racist who despises queers of all varieties and believes poor people should be punished for being poor.

I’ve ceded the determination of God’s character to cruel people who seek to justify their actions. I don’t see myself returning to the community of believer and attemption to reclaim God from the White Christian Nationalists. My priority is human character.

God condemns the gay lifestyle!

Skill issue, an expanding group of people is fine with it.

God wants poor people to suffer!

What a jerk. Let’s help them anyway.

God created the patriarchy and women should humbly submit!

I blow a raspberry in your general direction.

Let’s be better than God. Kinder, more compassionate, more accepting, treating every person with dignity and guaranteeing human rights to all. We can set a good example for God. Maybe, with time, he can become someone worth worshipping.

Questions:

- What if we still had small, regional gods? Do you think that would increase or reduce wars and suffering? How might it affect progress and prosperity?

- Science isn’t morally pure. Eugenics and the genocide based started with scientific theories and ended with atrocities. Do you think morals and ethics are more or less effective with a religious framework?

- Is reducing suffering a Godly goal? Or a secular goal?

“What if we still had small, regional gods?”

I thought you Mo-mos DID have that! Don’t you become gods over your own planets or something? (If Hitler got posthumously baptized, he probably rules over his own Nazi Planet even now.)

The “interview with God” thing is the central gimmick of the “Coffee with Jesus” comic strip:

http://www.coffeewithjesus.com/

(I hate the strip, its author, and its Jesus character. Low-effort, smarmy fanwank. Give me “Perry Bible Fellowship” any day!)

Zla’od – did you even read the post?

I’ve never heard of the Coffee with Jesus website, and I don’t know what Perry Bible Fellowship is. This post isn’t about either of those.

Such an interesting hypothetical conversation with God, Janey. Thank you for sharing.

A while ago, as I delved into the problem of evil and different theodicies, I encounterd one interesting “criticism” of soul growth theodicies (and LDS theodicy has very strong soul-growth elements to it). The criticism goes something like this. Under a strong soul-growth theodicy, one who is not suffering may choose to turn a blind eye to others’ suffering because it might be inappropriate for them to intervene. God has a lesson for that person/those people to learn through their poverty/illness/accident/bullying/whatever, and, if I/we intervene to prevent or alleviate their pain, we risk short-circuiting the growth lesson that God intends for them to learn through their suffering.

I can’t remember which theology it was associated with, but the thinking was proposed to me that maybe the reason evil and suffering exist in the world (and God seems unwilling or unable to prevent/alleviate it) is so that we as believers will get off our couches and do what we can to prevent and alleviate suffering. As the Jehovah of your interview said, “If you wish, you can reject that premise. You can choose not to accept hunger, illness, poverty, deprivation. You can choose for the world to be a place without suffering. And because you are the ones with that power, it will matter that you’ve chosen that.”

Last Summer, Patrick Mason added a compelling entry into LDS thought on the problem of evil (TW for genocide) in an essay he submitted to Faith Matters’ Wayfare magazine. https://www.wayfaremagazine.org/p/rediscovering-god-in-rwanda He concludes his essay with this: “In Rwanda I sought understanding and gained in its place a witness. The God of Friday wants me to look. When I stare at his broken, bloodied body—in Jerusalem or Nyamata—I am convicted that this is not the world I want. I will tend to his wounds and accompany him to his grave. And then I will wait and watch and work. I will witness of the hope and rebirth that comes on Sunday. Not just that one Sunday so long ago, but every Sunday since and hereafter. Sunday neither erases nor explains Friday. What Sunday offers instead is hope that new life is possible and real.”

I am one small cog in a very large machine, and my influence does not extend very far. But I am convicted that God wants me in whatever small ways I can to try to prevent and alleviate evil and suffering.

Wow! just. WOW!!!

How literally do we take the atonement? If we really become one with Christ, we *are* him. And yes, it is a stupid cliche, but what would Jesus do? Would he walk past a beggar, saying, “Well, if I gave him money, he would just spend it on booze.” Would he refuse to forgive a sinner who ask his forgiveness, saying, “No, you need to suffer more.”

Christ told us what to do. He told the story of the Samaritan and told us to go and do likewise. When asked why the man was born blind, he said that so others can learn compassion. It wasn’t punishment for his parents, or punishment for him from some pre-birth sin. No, it was so us slow learners can learn from his suffering how to alleviate that suffering. Do we believe what Christ said, or not. If we don’t, then of course we can wait around for God to fix it.

What if we still had small, regional gods? I think there would be more wars and less progress and prosperity because our energy would be going to our goods. It would reduce cooperation and would justify the hate that war breeds.

Science isn’t morally pure. This is an interesting statement because I’ve never thought of science as having or promoting morals. Science is verifiable facts that grow and change based on evidence. The terrible things done with science or even in the name of science were done because of another set of morals in place either religious or secular (outside of religion but not because of some scientific code). Science is a tool. Hammers don’t have morals.

Is reducing suffering a Godly goal? Or a secular goal? In today’s world there are examples of both religious and secular suffering because of war. Reasons can be justified either way. To live and let live takes faith and that can be either religious or secular. It would be nice if the people could decide but usually it’s the leaders justifying one thing or another and the people following without question. It’s sad what people will do in a Christian Nation to anyone not Christian. The very premiss of National Christianity isn’t a religion I want to be a part of.

I’m not smart enough to understand how the God of the Old Testament is the same being as the God of the New Testament. Talk about bi-polar. So just for fun let’s pretend that the God of X Testament is the product of the authors from X era. Therefore, we really have no idea what God is really like (if indeed he exists).

I’m neither a christian or a buddhist. If I win the lottery, I’ll go visit that sacred fig tree. But I don’t believe in Noble Truths. Unless it’s the one from Ecclesiastes– ‘but time and chance happeneth to them all.”

I kinda like science. I believe in measurement and questioning. Examining the empirical evidence and trying to proven through testing that the hypotheses are wrong.

The trouble I see is the unexamined assumptions that informed many scientists worldview. Evolution is the change in species over time. There is no end goal. No ascent of man. Yet the quirks of geography were cherry picked as evidence of superiority. Just so stories about the ascent of civilized white men. 2001 may be a great movie, but hominids learning to kill other hominids by beating them with a femur, doesn’t lead to spaceships and moon bases. (and analysis of hominids bones shows evidence of the community using scarce resources in caring for the sick and wounded.)

But 2001 is also part of our narrative. (The cynical me, says, Oh, so the masses must suffer so the right sort of people progress.) It joins with other narratives of suffering I’ve seen people apply to themselves and others. I need to be punished, so I must suffer. Or it’s somehow character building. No pain, no gain. Suffering purifies the soul. (A reason the inquisition tortured heretics. Christian love extended in purifying the souls of the most needy)

To quote a recent narrative, Victor from the show Arcane–“I thought I could bring an end to the world’s suffering, but when every equation was solved, all that remained were fields of dreamless solitude. There is no prize to perfection.” I do not know what that means, so I’ll just spin the wheel and do what I can.

Two nights ago I watched Hadestown for the first time. The song “Why We Build the Wall” has been on my mind ever since. I’m not sure it was written for our current White Christian Nationalist party but it could be their anthem.

The Greek gods make as much sense as our current diety, who tbf seems like a prick right now.

I keep re-reading Anna’s comment. Thank you.

Also what Josh h said.

Trevor Holliday, Hadestown is incredible! I wish everyone could see it. While my favorite song is “Wait for me” I definitely identified “Why we build the wall” with our current sad state of things.

I just watched the lyric video for ‘Why We Build the Wall’ on Youtube. Yeah, that really resonates with current events the way they are.

So many have left thought-provoking comments. When I had my first faith/trust crisis, I emerged from it with a broader and more benevolent view of God. Over the years, through many smaller faith/trust crises, that version of God has been crumbling through my fingers. In post-Mo parlance, my shelf broke. Rather than trying to create a God that I want to worship, I’m studying out the nature of God based on what’s actually in the scriptures and in the world. I used to be able to rationalize away stuff with the best of them, which is why those arguments have no effect on me anymore. I lived by them for years and then discarded them.

Trevor Holladay brought up the Greek gods. I admit I’ve seen some logic in why the Greeks believed gods were like that. I’m not going to worship Zeus, or whatever, but the idea that the Powers That Be are actually a whole bunch of people who may or may not care about humanity makes a lot more sense than believing there is one all-loving all-powerful God who has a plan.

It’s not that I think we should achieve perfection and reduce suffering to zero. Suzanne’s reference to “dreamless fields” is poetic and it isn’t something I’m striving towards. I just want to know where I fit. And if I can devise a theory of God that works, and that isn’t just wishful thinking on my part, then I’ll have a better idea of where I fit. In the meantime, I do what I can to make the world a little kinder and a little more accepting. The journey matters.

Instereo – thanks for your thoughtful answers. You’re right that science doesn’t have morals; science is a tool and the morality of humans is what determines how science is used. More and more, I’m thinking that religion doesn’t really have morals either. The morals of the believers determine whether religion is good and moral, not religion itself. Religion is a tool too.