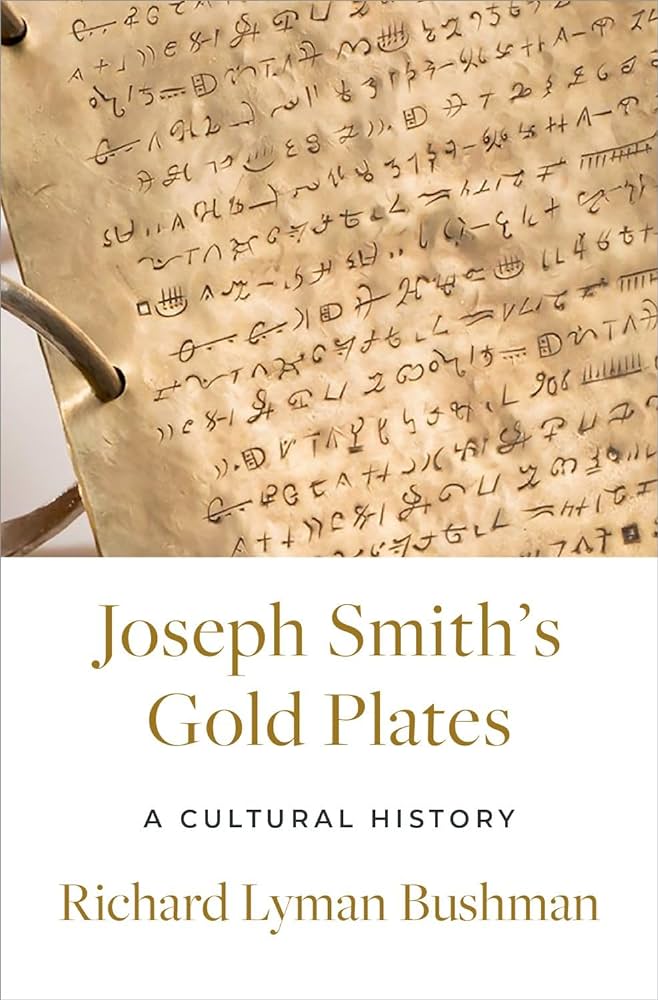

Let’s talk about Richard L. Bushman’s new book, Joseph Smith’s Gold Plates: A Cultural History (OUP, 2023). I made the image of the cover really big so you could see the characters. If you follow the link to the publisher’s page, you get an abstract and a table of contents. Like all of Bushman’s books, this one is insightful and informative. It is also in many ways frustrating. It’s a book that won’t make anyone happy: (1) rank and file believers will be offended by his frequent use of critical as well as supportive sources; (2) apologists will be appalled by some of his admissions (such as that Joseph started out with a treasure and guardian spirit model and only gradually moved to a sacred record and angel model); and (3) critics will be put off by Bushman’s tacit assumption that there was a real Mormon and Moroni who engraved figures on actual metal plates, later discovered by Joseph who somehow translated them with the help of an angel, buried Nephite gems, and seer stones he dug up around town. Maybe a “cultural history” is supposed to do that. But I’d be happier if he had written “an actual history” or a “critical history” or even “a defense.”

I say “tacit assumption” because Bushman never really spells out his assumptions or beliefs about the plates, although most of the text seems to just go along with the orthodox account of Nephite prophets, real metal plates, and supernatural translation. At the same time, he doesn’t make much of an attempt in the text to explicitly defend the orthodox story. He often details two or more views or theories about some aspect of the existence or history of the plates without coming down on either side or defending any conclusion. For example, at pages 136-37 he considers the following question: “Were the gold plates to turn up in a museum, what story would they tell?” He’s talking about museum curators and directors, and how they would display the plates, what kind of additional objects and explanatory material they would present. He then gives a paragraph outlining four options (and I’m quoting the first sentence or two of each of his paragraph-long descriptions):

- The Jospeh Smith story of a naive boy led by an angel to a precious, ancient record that he was required to translate.

- The critics’ stories of an imposture contrived to deceive the public.

- Abner Cole’s story of gold plates evolving from money-digging. A variant of the imposture stories …

- The plates as an instance of ancient record-keeping on metal sheets. The search for parallel artifacts …

He then sums up by saying, “Considered as a group, the four stories sum up how modern people think about the plates.” He then discusses each approach for three or four pages, but under the guise of “how would a museum director present the gold plates as an exhibit.” Bushman doesn’t really weigh the theories or present evidence for or against them. Hey, it’s a cultural history. Like I said, kind of frustrating.

The second half of the book is rather more interesting than the first half. The first four chapters cover in a more or less chronological sequence the familiar events of the orthodox story of discovery of the plates and the translation of the characters on the plates, albeit with a fair amount of discussion of sources that give information not part of the orthodox narrative and that most LDS would consider “anti.” The second half of the book is more topical, with discussions of rationalism, fiction and psychology, artistic representations of the plates, instruction in missionary lessons and LDS curriculum, scientific approaches, and finally global perspectives taking a religious studies approach looking at various accounts of records on metal plates or other examples of recovered histories.

Chapter 8, “Instruction: 1893-2023,” is a lot more interesting than you would think. One point he makes is that in the early versions of the scripted missionary lessons first promulgated in the 1950s and revised in the 1960s, the Book of Mormon was presented as the fulfillment of biblical prophecy. Considerable coverage was given to the visits of Moroni and discovery and translation of the plates. The mid-1980s revision of missionary lessons “offered only a few lines on the recovery of the Book of Mormon.” Without much context, the investigator was simply to “read in the Book of Mormon and pray to know that it is true.” The current Preach My Gospel plan takes a similar lean approach, with little reliance on biblical ties (these days, many potential converts have little familiarity with or faith in the Bible). As Bushman summarizes the current teaching plan: “Nothing is said about witnesses, and biblical prophecies are merely listed. No argument is offered in support of the book in the manner of Richard Lloyd Anderson or LeGrand Richards.” (See pages 126-27 for the whole discussion.)

He contrasts that development with the courses of instruction in the LDS curriculum, from Primary to youth classes and Seminary to Institute. The whole plates, angels, and supernatural translation story has been retained and amplified: “Within the Church, however, new members and children growing up in the late twentieth century have access to ample information about the plates. The minimal accounts in the missionary plans did not carry over to inside teaching materials. Manuals and history books went into detail about the plates’ discovery and appearance” (p. 128).

I found the last chapter, Chapter 10, “Global Perspectives,” to be perhaps the most interesting. He opens with a paragraph that is an excellent summary of the book as a whole. I know readers hate long quotes, but here it is anyway:

This book has traced the history of the gold plates in the minds of artists, critics, believers, and scholars from Septembere 1823 when the plates first appeared in the Smith family down to the present. It took time for the idea of an angel and a golden book of records to fully register with the Smiths, but by 1827 when Joseph brought the plates home it was fully formed. In succeeding chapters, the book analyzes the role of the plates in the Book of Mormon, their part in moving Joseph Smith to translate, and then their effects on the Smith family and their friends. Critics and apologists almost immediately deployed arguments to dismiss or to defend the plates. In the late nineteenth century, the attacks lightened and the plates were seen less as dangerous imposition and more as a fabulous fantasy. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the plates took on many forms in popular literature and art and were subject to scientific analysis both by critics and apologists. This sequence of appearances and arguments constitutes, in my way of thinking, a history of the gold plates. (p. 157)

Then in the body of the last chapter Bushman casts further afield, looking at events and topics with little or no historical connection or relevance to the history of the plates as he described it in that opening paragraph. He discusses other examples of “found manuscripts” such as the Spaulding book, “James Macpherson’s alleged translations of epic poetry supposedly written by the Irish bard Ossian,” various apocryphal pseudo-biblical texts, and Masonic tales of records on metal plates. He compares the plates to the stone tablets of Moses and to Catholic relics over the ages. He talks about Max Weber’s theory of disenchantment, then references the attempts of recent scholars to recover some form of enchantment in the 21st century, although not necessarily in a religious form. In the last section, tying the plates to contemporaneous tales, Bushman notes, “The plates resonate more persuasively with classic adventure myths.” You’ll like this quote:

Smith can be seen as another rendition of Joseph Campbell’s Hero With a Thousand Faces. Smith’s story is reminiscent of Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit who stumbles across the ring of power and wonders what to do with it. Later, in The Lord of the Rings, he passes it to Frodo, a brave but simple soul who bears the ring to its final obliteration in the Cracks of Doom. In his reliving of the age-old story, the young Joseph Smith took on far more than he was prepared for when he brought home the gold plates. He was no more ready than Frodo to assume the burden. (p. 169)

So there you have it: the gold plates in history and imagination. Any author who insightfully compares Joseph Smith to Frodo deserves to be read by people like us. Although I object to Bushman’s description of Frodo as “a simple soul.” He studied the manuscripts Bilbo collected and learned some Elvish. He proved himself at times wiser than many of the wise elders he met on his big journey. He was no simpleton! And let’s give Tolkien some credit as well. He was an outstanding scholar of Old English, Middle English, Old Norse, and Germanic philology. He helped rehabilitate Beowulf and establish its now lofty status. He was also a dedicated Catholic. A variety of Catholic and Christian themes appear in The Lord of the Rings and other Middle-Earth texts Tolkien wrote. He wrote what some literary critics have described as the most popular books of the 20th century. If you are one of those people who has only seen the movies, dear God please read the books.

And don’t forget, although more tongue in cheek than a serious claim, The Hobbit was presented by Tolkien as a discovered manuscript! Bilbo wrote it and called it, among other titles, “There and Back Again” and “My Unexpected Journey.” That might have been used for the title of Bushmans’ book: Joseph Smith and his Unexpected Journey with the Gold Plates. Or maybe The Lord of the Plates. As Bushman notes in the very last sentence of the book: “Two hundred years later, the mystery lingers on, inviting reflection and inquiry and more than a little wonder” (p. 170).

I understand your frustration with Bushman in that he doesn’t really reveal his opinion on the entire Joseph Smith Golden Plates project. Many of us on W&T have a definite opinion on this topic and so we are frustrated that an author with more knowledge than most of us is unwilling to take a stand.

But Bushman is an historian and academic and author and he wants to present an open minded presentation even if many of us suspect that deep down inside he has real opinions on these topics. He has a brand and he has relationships to maintain and he’s not going to jeopardize those just to satisfy progressives. I wish he would and to me he seems a little inauthentic but I get it.

“Two hundred years later, the mystery lingers on, inviting reflection and inquiry and more than a little wonder.” I’m not sure the mystery really lingers for all that many people at any given time. If you’re a TBM, you assume that plates are sitting on Moroni’s coffee table in the sky. If you’re not a TBM, presumptively, you’re willing or at least free to pick and choose among the various non-miraculous theories as to the book’s origin. I just don’t think there are that many folks really sitting on the fence for very long over the issue once they start to study the subject in earnest. What they decide to do with that information however may take a lifetime of evaluation and re-evaluation.

As for Professor Bushman beating around the “non-literal believer’s” bush, the man is in his nineties. If he wanted to come out of the non-believer’s closet many think he lives in, he would have done it by now.

My question is this: Why in the wide, wide world of sports did he write this book? I mean, this is Richard Lyman Bushman. No one in Mormon academics is revered more highly. Don’t get it.

Glad you caught the glaring error of describing Frodo as a “simple soul.” Need less to say IMHO The Lord of the Rings is more believable, cohesive, and spiritual than the BOM.

My suspicion is that Bushman wrote this work to defend academic scholarship from the Yahoos on both sides of the LDS cultural divide. For a believer to display control of his potential bias and treat opposing theories with such equanimity and creativity… I think he is trying to point a way forward for the faithful and fair to calmly analyze such thinking without resorting to histrionic apologetics or overt materialistic assumptions. “Rough Stone Rolling” was an example of a faithful analysis from a post-modernist perspective. This latest work seems to take that just one step further.

Sounds like a book in search of an audience. I just don’t see the church or even most members and nonmembers able to defend such a position as you say.

@Old Man, disbelief- in the part or towards all of the church’s spiritual or religious claims -need not be necessarily based upon “overt materialistic assumptions”.

Social Constructivists come in both the ‘thick’ and ‘thin’ variety, neither of which could be described as strictly materialistic in explanation of the world. Yet nor need they rely upon any of the aforementioned (religious or spiritual) skyhooks to explain the BoM.

It’s a false dichotomy- The presentation of which assumes the greater assumption on the part of the critic than the believer. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and the responsibility to provide said evidence is upon the believer who claims a phenomenon’s existence. Comparison of the evidence must then be examined- which needn’t be strictly material.

Social constructs for example are intersubjective and co-constitutional. They cannot be explained through material processes alone.

Your argument also implies (without evidence) that the truth of the matter lies somewhere in the middle. This too is a fallacy, but one that’s easier to make when one flattens the range and scale of possible arguments, and makes a scarecrow of those disliked.

Excellent review. I vote for more book reviews.

Too much of the Mormon culture is dependent on folklore for testimony. Joseph did not translate ancient record by script or characters—all of it is by vision. Gold plates are irrelevant to the Restored Gospel. Unfortunately, however, most folks need a magical story to frame a belief system, so it seems a magical story developed into proper modern myth for the cause of Mormonism.

Consider: is Joseph Smith more a prophet if he indeed translated ancient script—or is Joseph more a prophet, if he translated his visionary, dream-like experiences? For me, I’ll take the visionary over the scribe.

Gold plates are part of Mormonism’s folklore, not part of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ.

Travis,

I’d say that the gold plates are part of the restored gospel in that they embody the reality of living witnesses of Christ. The plates are as real and as tangible as the people whose words are engraved on its pages.

The Joseph Smith – Frodo comparison is silly, simply because Pippin is a much better fit for Joseph … since Joseph likely was Pippin (Hyrum was, of course, Merry)! Bushman’s analogy is way off…

Here is a brief post I wrote a little bit ago introducing Joseph as Pippin:

https://coatofskins.blogspot.com/2023/07/joseph-and-hyrum-pippin-and-merry.html

As for Frodo, JRR Tolkien himself as that character is a much better take or comparison:

https://coatofskins.blogspot.com/2023/08/elijah-in-england-jrr-tolkien-and-frodo.html

This was a great book review, and I’m honestly glad to see more work from Bushman. I’ve always appreciated the old quote from Bushman about New Mormon History: it is “a quest for identity rather than a quest for authority.” This book seems to fall into that same approach, which is also what makes it feel so elusive for believers and non-believers alike.

Theories about physical gold plates and BoM geography are sure fun, but I believe that cultural history and the quest for identity are more useful to modern Mormonism.

The most fantastic claim made by Joseph Smith is that he was visited by and interacted with angels (Moroni) and resurrected beings (John the Baptist). These claims are impossible to prove or disprove. One either believes the narrative or considers it a fabrication.

The Book of Mormon invites unusual scrutiny because a book literally exists. And while critics find various parts of the book unbelievable, the entirety of the book defies explanation. For example, critics point out that various themes and narratives discussed in the Book of Mormon were in circulation in the period Joseph Smith lived. Let’s assume that is true. It is still an incredible idea that a young adult farmboy collected these various ideas, comprehended them and then integrated them in a 500+ page novel!

And Joseph Smith not only produced the book but he simultaneously devoted considerable time and effort saying and acting on the claim that the book sourced from ancient records. If Joseph Smith claimed the Book of Mormon sourced from pure inspiration would that change how critics looked at it? Can appreciation and criticism of the Book of Mormon be separated from the question of plates and angels? I think yes. We can appreciate or not the words of any text without knowing how the text originated.

But the Book of Mormon story begs the reader to consider the narrative is real and literal. The characters in the book talk about keeping and preserving metal records. The book prophesies of this record being published. I have sympathy for those who find the entirety of the Book of Mormon story inconceivable. Such, however is the case of any miracle, and ultimately what the book demands readers to believe is that it is a miracle.

“Were the gold plates to turn up in a museum, what story would they tell?”

That Bushman includes this and the answers you listed in his book is telling. He seems to think that if this were a reality that it wouldn’t really change views or have too much of an impact on the way things really are. And that there would still be skeptics saying the same things. No. Not at all. If we found the gold plates and could date them with the highest degree of confidence to the ancient Americas sometime between 600 BC and 400 AD, that would be without a doubt one of the most significant historical findings ever made. Just the fact that there were gold plates with inscriptions on them even if we couldn’t decipher them would be massively significant. It would change history books and how we perceived the ancient Americas. It would be groundbreaking on the level of the Rosetta stone. If we found a way to decipher it and it revealed writing in an alphabet that was similar to ancient Egyptian and/or ancient Hebrew that would be even more phenomenal. The most phenomenal, of course, would be if we were able to decipher it and found that it talked about Jesus Christ. The discovery of an ancient that proved the existence of pre-Columbian Christians in the Americas would be one of the biggest historical discoveries to date. Either Bushman doesn’t understand this, or he actually does and is deliberately downplaying it.

Believing intellectuals and apologists actually play down the significance of the Book of Mormon. They undersell it. They claim belief that it is historical, and often that there is strong evidence of its historicity. At the very least, they claim that the Book of Mormon’s historicity cannot be debunked. Look, if you know that you have a document and a evidentiary narrative so strong that shows the existence of Christians and Jews in the pre-Columbian Americas, why aren’t you shouting it from the rooftops? Why aren’t you going to academic conferences, the press, museums, and anyone you can find and showing to them that Christians existed in the ancient Americas? The reason for this is likely because in the back of believing intellectuals’ minds, they actually have some doubts about the Book of Mormon. They know that their defense narratives of the BOM won’t actually pass muster in a larger academic setting. Their myriad extremely verbose publications in defense of BOM historicity are really only meant for the already believing as a sort of ploy to keep them from openly doubting or exploring ideas that would go against the church’s officially accepted narratives. They also write those narratives for themselves as a sedative for the continuous cognitive dissonance that they must experience by virtue of being an intellectual who professes belief in a bunch of hard-to-believe ideas and propositions.

A part of me actually feels sorry for Bushman. He knows he has to maintain legitimacy among the believing Mormon community and that there are lines that he cannot cross. He doesn’t want to sacrifice his reputation among the believers, so routinely falls short of indulging more plausible and logical explanations for BOM historicity. That said, he is a brilliant historian and I deeply admire him for his work.

That was an enjoyable read. Bravo Dave B! You get my vote for post of the year.

@Jack,

Understandable, given that is how we tend to indoctrinate in the Church. I’d say Joseph could have “translated” his visions of the record of ancient peoples without any plates. In fact, the speed and method of Joseph’s “translation” of the Book of Mormon is described more like stream-of-consciousness, rather than a translating of language like a scribe. If some folks need a magical story to emphasize a belief system for worship, that is okay—but it’s not for me. The idea that Joseph made-it-up-in-his-head, or translated imagery from his inner experience, is far more convincing than the silly folklore many LDS folks turn to worship. We tend to worship the magical folklore to the extent that it substantiates testimony… and in this way golden plates become Golden Calf.

Thanks for the great comments, everyone.

A couple of extra observations. First, the book is fairly short, coming in at 170 pages of text plus two short appendices. Honestly, I expected him to have more to say on this topic given the twenty years he’s been working on it. Second, as I sort of suggested above, the book is better at raising questions than answering them. That isn’t the way historians typically write books, but then the gold plates are not an easy subject of study for normal historical research and writing (even the orthodox LDS story tells us they don’t exist anymore, at least in the spatial and temporal here and now of Planet Earth).

To the several commenters on Bushman’s perspective or motivation: I’m not really coming down on Bushman in any negative way. It’s his book and that’s how he chose to write it, from the middle or neutral part of the spectrum, while at the same time sort of leaning toward the orthodox side of things. I was less frustrated by the end of the book than I was halfway through it. It’s definitely worth reading. Maybe Terryl Givens will give us an updated edition of By the Hand of Mormon. That’s probably the book I’m hoping for as opposed to this focused reflection on the gold plates.

Seeker: “Why did he write this book?” I think after years of studying and researching this narrow topic of the plates, and in view of his age, it was time to publish what he had. He could have added three more chapters engaging with Terryl Givens and John Sorenson and Grant Hardy, but he didn’t.

Pirate Priest, great point about identity. How does a religion define its identity in an age of science and skepticism? That’s a tough one and it’s certainly not just a Mormon problem. I’m sure Catholic intellectuals struggle with lay members’ belief in literal transubstantiation and Protestant intellectuals struggle with lay members’ belief in inerrant scripture (neither of which stand up to an hour of reading and common sense). What’s different in the LDS Church is that the senior leadership leans more toward the folk beliefs of the laity than the informed beliefs of intellectuals and historians.

“The plates are as real and as tangible as the people whose words are engraved on its pages.”

Clever.

Travis,

I agree. If the words of the Book of Mormon speak truth to your soul, follow it’s teachings. It doesn’t have to have literal historical backing to be “true” as a narrative about following Christ. Joseph Smith was a human being sometimes inspired, sometimes not so much, but his inspiration in how he wrote out the Book of Mormon, is in general, magnificent.

How much does Bushman write about Baird Spaulding?

The BOM has one major flaw: it’s boring.

D’oh! Solomon Spaulding, not Baird Spalding. Never mind.