Often in high demand religions like ours (or as one wise friend posited “wrong demand” religions), church members are hyper-vigilant about orthopraxy, watching for outward signs that an individual is breaking the rules.

On a recent tour in Tahiti, our tour guide talked about the usefulness some of the chiefs found in using “taboos” to control individuals who have been troublesome or demanding. The leader declares that the person’s problems have been caused by a curse and explains the actions that must be taken to undo the curse, things like only eating meals at specific times and not touching the food with your own hands, requiring others to feed the person. This process sidelined the “troublemaker” by taking away the luxury of free time that allowed them to complain or petition the chief. So long as they operated under the strict taboos, they didn’t have time to make trouble for the chief.

This concept reminded me of the strictures placed on Hassidic Jewish women as described in the memoir Unorthodox (also on Netflix–highly recommend!) I read Chaim Potok books as a teen, and these books described a world of orthodox Judaism from a male perspective, but reading Unorthodox, it seems to me that the men have it much easier. The women have rules around their menstruation, many rules around cooking and eating and cleaning, rules about conception and sex, gender segregation in worship, modesty rules, purification, and married women are required to shave their heads and wear a wig in public! When our heroine sheds her wig while wading into a lake, surprising her new friends with her shaved head, we can feel the freedom she feels. She is, for the first time, choosing her own comfort over the rules. She is trying to learn to value what she wants without being told what she must do, what she should want. Now that she is no longer in the Hasidic community, these strictures don’t make any sense for her.

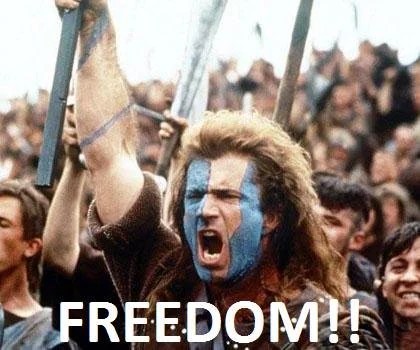

Personal rebellion can lead to personal freedom by empowering individuals to break free from constraints, limitations, or oppressive situations that have been restricting their choices, self-expression, and personal growth.

- Questioning the Status Quo: Personal rebellion often starts with questioning the status quo, challenging established norms, and critically evaluating one’s own beliefs, values, and circumstances. This process of introspection and critical thinking can lead to a deeper understanding of one’s desires, needs, and aspirations.

- Breaking Free from Conformity: Rebellion often involves resisting societal or familial pressures to conform to certain expectations, roles, or behaviors. This can include challenging traditional gender roles, career expectations, or cultural norms. By refusing to conform, individuals assert their right to make choices that align with their own values and desires.

- Seeking Authenticity: Personal rebellion involves embracing one’s true self, including one’s identity, beliefs, and interests, rather than conforming to external expectations or pressures. Seeking authenticity allows individuals to live in alignment with their genuine feelings and values.

- Exploring New Paths: Rebellion often encourages individuals to explore new possibilities, whether in education, career, relationships, or personal interests. This exploration can lead to new opportunities and experiences that were previously unavailable or unconsidered.

- Risk-Taking and Courage: Personal rebellion requires a willingness to take risks and face uncertainty. This risk-taking can lead to personal growth and a sense of empowerment, as individuals learn to overcome challenges and adapt to new situations.

- Independence and Autonomy: Rebellion can be a path to gaining independence and autonomy, as individuals make decisions for themselves and take control of their lives. This may include financial independence, living on one’s terms, or choosing one’s own life path.

- Overcoming Fear and Limiting Beliefs: Rebellion often involves confronting and overcoming fear, self-doubt, and limiting beliefs. By doing so, individuals can expand their comfort zones and embrace greater personal freedom.

- Building Resilience: As individuals face adversity and challenges, they learn to adapt and persevere, which can contribute to their overall sense of freedom and self-reliance.

- Self-Advocacy: Advocating for one’s rights, needs, and desires can lead to improved communication skills and the ability to assert oneself in various life situations.

- Enhanced Well-Being: When individuals are free to live in accordance with their values and authentic selves, they are more likely to experience happiness, satisfaction, and a sense of personal freedom.

Those who break Mormon rules are considered “rebellious” by believing members, but perhaps that word doesn’t really fit the experience of breaking the norms of a community you no longer consider your own. Along with the charge of “rebelliousness” there seems an implicit agreement in an authority–the church or leaders–whose edicts must be obeyed; ignoring these edicts is considered rebellious if you agree that they are “binding” or that they have authority in your life, in other words, if you believe the church to be what it claims to be. But if you don’t believe that, then your actions are not “rebellion” so much as the freedom to make your own choices. You can’t rebel against an authority you don’t recognize as valid. Or maybe that’s what rebellion means, at least in the early stages, transgressing norms you previously adhered to in order to experience your freedom.

What does it sound like when church members consider others to be “rebelling” (rather than free)? Here are some examples:

- They secretly know it’s true.

- They are just too lazy or weak to make the sacrifices needed.

- Wickedness never was happiness; they now have a spirit of darkness.

- They are easily led astray by others.

- They are addicted to [drugs, sex, porn, alcohol, coffee, tea].

- They wanted an excuse to sin.

- Their life is falling apart now (getting divorced, losing friends, etc).

To go back to the cult vs. culture discussion from a week ago, there are those who feel that they have escaped a cult; for them, perhaps rebelling is a more accurate description. Their need to break away from the bonds of authority and social norms might feel like a more deliberate act. While church leaders like to say “they can leave the church, but they can’t leave it alone,” for those who experienced trauma, the reality may be more like “you can leave the church, but the church doesn’t leave you.” It may feel like the voice of an abusive parent, stuck in your head, if you experienced religious trauma.

For others, the more apt analogy might be going from one culture to another; you adhere to cultural norms within a context. When the context changes, so do the norms. If you attended a school, for example, and that school had a specific dress code and curfew, you stop adhering to those rules when you graduate. You are now free to explore your own decision-making, to make your own rules about when to go to bed and what to wear. You no longer worry about the opinions of your classmates because they are no longer your social circle.

Of course, if you are still in the church, seeing people who have left it breaking the norms to which you still adhere can be distressing. There’s a reason people employ the “they left to sin” trope. Some may resent the freedoms other enjoy if they resent the Mormon rules that are being discarded by others. Or they may feel confronted with a need to defend to themselves why these rules are important to them, why they choose to continue to follow them. Or, if they do agree with and believe in the norms and rules, they may feel judgmental of those who no longer adhere to them. They may find it comforting to blame those who don’t follow the rules as morally inferior or to insist that they will be unhappy with their choices.

We’ve also talked here about the difference between a “high demand” religion and a “wrong demand” one. When rules feel arbitrary or indefensible, it can feel as though sacrifices members make are meaningless and taken for granted, only designed to reinforce group isolation, not to foster any moral growth. The more we ask of members, the more we foster judgmental attitudes, and the more people will resent those sacrifices if they eventually choose to leave the group. There’s a reason the Amish have Rumspringa, but the Presbyterians do not.

- Do you see value in this framing of people who have left the church breaking the norms?

- How do you distinguish between someone being free and someone who is rebelling?

- How do you see members handling it when their family members or friends discard church norms and rules?

- What norms do you think members are more tolerant about former members discarding? Which cause more distress and conflict?

Discuss.

A) “Framing of people who have left the church breaking the norms”?

My faith transition was triggered in part with learning more information about myself in line with mental health/lifestyle labels/clinical conditions. It was easy for people to just “write my situation off” as “a part of the condition label”.

B) “How do you distinguish between someone being free and someone who is rebelling”?

Rebellion usually includes little concern for the consequences to others as well as the consequences to self. Rellion also implies “superior control being disregarded”, because there needs to be an “authoriative figure” to rebel against in a zero-sum, “us vs them” mentality. “Being Free” does not have either framing.

C) Most of the time, someone who walks away from church activity is viewed as a threat by the person who wants to be validated/encouraged in their church activity and worldview to the degree of that person’s need/desire for that validation/encouragement.

D) I think that the tolerance depends on exact impact to the current member, how “deliberate” the usurption of moral authority vs church authority is, and whether it impacts a “gender performance” aka expectation.

Whether or not an action is defiant rebellion or freedom seeking rebellion probably lies in the intent. In simple defiance you’re still tethered to the thing causing resentment- you’re just moving in the opposite direction. However if you seek freedom from a legitimate desire for personal integrity, the rebellion may become less selfish and more about self authenticity.

There will always be a balance between desire to belong to a community and a desire to belong to yourself. In my experience the LDS church tends to take advantage of the need to belong to a group and devalues the individual. To make it worse it happens when we are most vulnerable; kids and adolescents trying to figure it out. In my experience the kids who are successfully able to shed unwanted LDS expectations have to push so hard that it seems rebellious and unbecoming. Honestly it’s probably the only option for a lot of those kids to leave something so extreme. Even those leaving later in life probably have to act defiant to get momentum going in the new, desired direction.

I’ll add one thing to the list of why people rebel and leave the LDS: the cliche midlife crisis. Having left in my late 40s and suddenly having more money and time, I’ve traveled and taken up a hobby I’ve always wanted. I’m certain some, including my ABM wife, wonder when I’ll snap out of it and return to normal. My rebellion has been a trip to Italy and climbing a mountain – one with my wife and one with my son. If that’s rebellion then it’s going to keeping rolling.

When a neighbor leaves the church, it’s something to gossip about. When it’s a member of your family, it’s something to hide.

If you’re the one leaving the church you really don’t care what your neighbor thinks, you worry about hurting your family, particularly your mother or father.

Finally, isn’t rebellion about freedom? Of course, there are those who say rebellion can cost you freedom but there’s a big difference between opioids and coffee. There is also a big difference between rebelling against a political state and a religion which really only has the power of suggestion and community. I think the biggest factor to be considered with rebellion is how deep the roots of association are with what you are rebelling against. A person with no other members of their family who has only been a member for a short time even if it’s a number of years, is not a big rebellion but someone with generations of family both in time and numbers is a much bigger rebellion with bigger consequences for their freedom. They might be free from the constrictions of the church but not from the reprisals from their family. It would be almost like starting over again and if they are all alone, will they have the “strength” to stay away?

The thing about parents being hurt if you leave the church is basically BS. If they are good parents they will honor and love you. If they feel inadequate about their parenting vis a vis your decisions it’s on them. We cannot live our lives afraid to cause “hurt” to other people unless that hurting is caused by unjust dominion, eg physical abuse, bullying, etc.

I have collected some comments from a Utahn who prides himself on being an acute observer of the human condition. Here are a few:

“I hate to drink socially with ex-Mormons. Regular people drink to enjoy a good beverage and the company of friends. Ex-Mormons drink to get drunk and act stupid. They may as well do it alone.”

“Ex-Mormons can never really stop being Mormons. They are still so busy rebelling against Mormonism that they don’t even know themselves.”

“Ex-Mormons define themselves as being ex-Mormons. What they don’t realize is that they are so adamantly opposed to Mormon things that they are as fundamentalist in their thinking as a modern LDS fundamentalist or polygamist, just in a different way. Their cognitive bias just screams at you.”

If my friend is even close to correct, those who “rebel” from the church don’t find the freedom they desire. There is much danger in rebellion.

How do you see members handling it when their family members or friends discard church norms and rules?

Like most things in life, there is a continuum of the way members “handle it”: on one side there is fear, anger, and judgment, and on the other is love, acceptance and tolerance. Each family, each person, is somewhere on that scale. And maybe initial reactions, often rooted in toxic (but longstanding) church and family culture, start on the fear and anger side. I have often seen, however, that over time, people evolve in their views and evolve as people. Many come to see the culture of judgment and disdain towards those who choose to leave the church as toxic, and come to realize that connection, relationship, and love are what is important and where we want to be.

I can say this personally: fifteen years ago, we often had awkward family gatherings, like at Christmas, where those who had left the church and those who had stayed didn’t quite know how to be together. But now, 15 years later, we are one happy, laughing, messy, complicated, loving group of people who accept each other the way we are, and truly enjoy being together. It is so much better that way.

These things are a process. Hopefully we can look into our own hearts and see that we are moving to the loving side of the continuum.

When I first decided I am never going back to church, I got double piercing in my ears, and bought a necklace cross. I wanted to make a statement to myself that I was still Christian, but no longer Mormon. Was that rebellion, because I was purposely doing that which had been forbidden as a statement? Or was I claiming my freedom because I had long wanted a second piercing?

I think now that I was claiming my freedom because it was for me, to declare myself to myself as no longer Mormon. I wasn’t doing it for the ward members to see that I was no longer one of them. Nor was I doing it to declare that I had no respect for the authority of the institution. I see freedom as doing what pleases oneself and rebellion as an act against some other. The direction of the action is different. Is it for me or against them.

Word of wisdom seems to be a big one that members object to in an apostate. The apostate sees prohibitions against coffee and tea that are good for you, as a silly rule to mark you are a member of the in group. Members kind of see it the same way. It is SO easy to avoid coffee, that members see drinking coffee as a deliberate act of apostasy. I think the church started using it as an in-group marker to keep Mormons unique, and so members see it as the apostate deliberately announcing a rejection of the group. Choosing adultery is a “mistake” but drinking coffee is a “sin”. The coffee is seen as more deliberate, therefore worse. Because it is so easy to turn down a cup of coffee, but somehow harder to keep your damn pants zipped up. Yeah, I think that is kinda backwards, but it is because adultery is not out-group behavior, but a mistake for all religions, while coffee is out-group behavior, something only nonMormons do.

I wanted to sin. I wanted to wear tank tops.

Out of order? Yes. Over simplified? Yes. Tongue in cheek? Yes. Still, the response from others was much greater than warranted.

It’s amazing how my perspective on that list of 10 items has changed. When I was a TBM, I looked at that list with a very suspicious lense. For example “exploring new paths”. That seems dangerous when you already have the official path laid out before you. Why would you need a new path? As a post-TBM, I see this list as totally liberating. In fact, I don’t see how you can live a full life without embracing most of these items. What was suspicious before is now liberating.

What vajra2 said about parents X 1000. Your question about being free vs. rebelling is apt, I think. I’ve had a steady, gradual faith transition from being a semi-orthodox/orthoprax believer to being PIMO to being likely just O next year. This transition isn’t about rebellion, it’s just been about what works or doesn’t work for me. I gradually came to realize that: church is boring and devoid of meaning (at least for me), Mormon teachings/doctrine/practice do at least as much harm as good, and Mormonism writ large simply isn’t “true” in the way that most believers mean that term.

This means that, while I disagree vehemently about the church’s view concerning LGBTQ people, the role of women, its general conservative bent, and its hugely problematic (racist) past and book of scripture (the B of M, among other things, really is a handbook for white supremacy), I don’t stand up and yell at people during fast and testimony meeting, I don’t buy a Harley and tear around the church parking lot, and I don’t start fights or try to provoke people at church. I make a few comments here and there in Elders Quorum, but other than that, I just sort of quietly do what I do, so that feels less like rebelling and more like not even freedom so much as just living a life that’s more suited to me. The church’s teachings just don’t mean that much to me. If there is an afterlife, I’d want it to be pretty similar to the life I’m building here: full of (mostly country) music, lots of dogs, a few friends and my spouse, with whom I could have long, meaningful conversations, and regular visits from my children, along with a telecaster or two. I don’t want to build worlds and I don’t want a thousand wives/baby factories in the afterlife. I would like to create some stuff, but other than that, I’d be good with calm and serene, punctuated by meaningful bouts of passionate creation/self-expression. And maybe some fishing.

So to me, that’s not rebellion. Truth be told, I do nowadays enjoy the occasional iced tea and espresso frappuccino, and I don’t wear my garments, but those things are about comfort and things I like, not about rebellion. It’s never a good idea to do anything because you think someone else won’t like it. I drink iced tea because I like it, that’s all. Someone else mentioned a midlife crisis and while I don’t think I’m having one of those, my advancing age (I’m 58) means I don’t have a ton of years left. Ironically from a Mormon point of view, I suppose, that has made me want to focus on the things that make me happy right now, not on some vague, undefined (even by Mormonism) afterlife that no one has any details about. I have no idea what the afterlife is like, even if there is one, but I know beyond the shadow of a doubt how wonderful and miraculous it is to be in a Nashville honky tonk on a Saturday night. I’d rather be there.

For me number nine, self-advocacy, is huge. Though my decision to step away from my family’s faith tradition is really complex, over time self-advocacy seems to be the thing that keeps me from going back. My current family is made up of a rainbow of people and self-advocacy means not attending as the space is just not safe.

Unlike Old Man, I cannot categorize post-Mormons the way his friend has. Perhaps a part of that is age. But I’ve seen people that leave come in all shapes in sizes. To focus on his one example re alcohol, I associate with post-Mormons that still don’t drink (like my wife), post-Mormons that drink socially and responsibly (I see this one most commonly), and post-Mormons that swing the WoW pendulum as far as they can.

On that same idea, I see TBMs that aren’t interested in relationships with post-Mormons, TBMs that are interested in relationships with the post-Mormons they met as Mormons, TBMs that are interested in relationships with post-Mormons as long as they don’t talk about it (most common in my experience), and TBMs that are interested in all sorts of relationships.

Long story short, I didn’t see my journey as rebellion at all, though I’m sure an outsider reviewing my file may find instances where I said or did something simply to ruffle feathers. It happens and I’m not ashamed to admit it. I’m doing my best, which is not great sometimes. Also, if your current social network isn’t working for you, don’t be afraid to find a better one. There are post-Mormon groups that are not just trauma bonding, and there are TBMs willing to see you as a person.

I’ve long found it curious in not just Mormonism but many other religions that believers claim to accept free choice as to one’s commitment to their respective religion. They claim to be and often sincerely show acceptance and tolerance of others who are not of their faith. But as for those who were born into or accepted the faith and then left, that’s another question. In those cases, believers often seem prone to find acceptable stances of ostracism, shaming, high pressure, fault-finding, chastising, pressuring to divorce, blaming, ridiculing, shunning, and other forms of coercive behavior towards those who leave. Doesn’t freedom of choice mean acting with decorum and respect towards those who leave the faith? Persuade them to believe again, invite them to return, sure. But don’t pressure them to get a divorce from their spouse. Don’t seek opportunities to rub it in their faces if something bad happens in their lives.

I always thought rebellion against church standards was pointless. Heavenly Father didn’t give us commandments because he wanted to restrict our freedom and hurt us, he gave us commandments to increase our freedom and uplift us. Wickedness never was happiness, right?

That didn’t last very long once I bonded with some LGBT+ people over shared interests, and realized that everything I’d been told about them was a lie. And that if this really was how god wanted them to live their lives, it was a tragedy. There was no good reason to hurt these people.

It was hard for me to become a rebel, but I’d always believed in “do[ing] what is right; let the consequence follow.” What was really hard was realizing what that meant for me personally, and acting on it.

It would’ve been easier if I’d learned to be more rebellious when I was younger, instead of being scared and raped and beaten into submission.

I believe we should be rebelling our whole lives. The status quo is frequently stultifying and in need of change. This is particularly true of organizations as they age. Ironically, we are living in an era of rapid change. Members of organizations need to encourage improvement in leadership. Members need to break up cliques. If members don’t want leave with their feet, they can always quit providing financial support or turn down offered positions, or both.

@Roger Hansen

I approve of any form of rebellion that involves “not giving money to a murderous hate group that defends sexual predators anymore.”

Actually, it’s kind of the bare minimum I expect of people.

@Old Man

There are a lot of obnoxious atheists on the internet, who were raised religious and are now always going on about how believing in god is stupid.

I think the common denominator is, the churches they were raised in taught that all the other churches were wrong, and people were stupid for believing in them.

Similarly, when you’re brought up to think that drinking coffee is the next-worse thing to an opioid overdose, and then you drink coffee and aren’t suddenly craving your next hit, you suddenly realize the people who taught you that were full of shit. This can lead to some extremely risky behaviours, since you never got any education about drinking alcohol responsibly, having a designated driver, or prioritizing your own comfort levels over societal expectations.

What I’m saying is, just like with every other reason exmormons are messed up, it’s mormons’ and mormonism’s fault.

Also, we can’t be friends if you’re currently giving money to a murderous hate group that defends sexual predators. I have higher standards than that.

We all rebel against God to some degree. The important question for most of us during the course of our lives is: do I have a pattern of rebelling less overtime?

On the one hand, the LDS Church isn’t like other “easy to join, easy to leave” Protestant denominations. You have to jump through some hoops to join (taught by missionaries, interviewed, promise to keep Mormon commandments) and take determined steps to formally disaffiliate (write letters, maybe get them notarized, maybe meet with a local leader), then eventually deal with social fallout from friends and relatives, maybe some stress in a marriage, maybe the end of a marriage.

On the other hand, it’s not like a criminal gang, where leaving may be followed by serious retribution, or the US Army, where leaving before your term of enlistment is up is very difficult. So we shouldn’t overstate the difficulty in leaving the Church.

I suppose we should ask *why* the institution and Mormon culture in general makes it so hard to leave? I’m sure some leaders like keeping membership statistics high by discouraging exit. Some true believers might think keeping mentally out people on the rolls will somehow improve their chances at celestial (or terrestrial?) salvation rather than slipping down into postmortal telestial regret. But let’s be honest: There are lots of rank and file members who positively *resent* those who leave because they secretly wish they could too, or at least wish they could live a normal life without tithing, garments, callings, incessant meetings, and maybe enjoy a coffee in the morning and a glass of wine in the evening.

Bottom line: most members don’t grieve for your lost salvation, they resent your freedom from Mormon constraints.

“If my friend is even close to correct, those who “rebel” from the church don’t find the freedom they desire. There is much danger in rebellion.”

@Old Man, when my child spoke to me about a decision to move away from the church and provided me with carefully thought-out explanations of the reasons, I had to do some deep personal reflection. I came to a different conclusion than you did.

I began to wonder if it had been dangerous for me to raise my child in a religion that focuses on doing certain behaviors in order to get a reward in heaven as many in the church do rather than basing behaviors on ethical principles as many in certain other religions or outside of religion do.

I wondered if it had been dangerous for me to raise my child in a religion that would have no space for my child if my child gravitated to a rational approach to life rather than a religion-based approach.

I wondered if it had been dangerous for me to raise my child in a religion that had somewhat random behaviors framed in the cloak of “morality” (No green tea because health but Red Bulls are just fine? The community that judges someone more harshly for drinking coffee than harming a child, per Anna’s comment above), so this child’s entire moral framework shattered when faith in fallible leaders and a fallible institution was lost.

I wondered if it had been dangerous for me to have raised my child in a religion where family members are rejected from their families if they choose a different path in life, even while living good and moral lives.

I’ve wondered a lot about the foundation I raised my family on and regret how I approached a number of decisions through the years.

I love many things about the church and my upbringing and my child’s upbringing in the church. But there are also some very serious problems in the church and members are not empowered to speak up about them. This is not a small problem.

Love the neighbor as thyself.—Jesus Christs

My religion is very simple. My religion is kindness.—Dalai Lama

Jack: It’s a fun trick to substitute “obeying God” for “obeying church rules.”

Anon,

The only conclusion I came to was that choosing to characterize an ideology as bad and oppose it draws a very tight box around one’s self and defines you in ways that may be less than positive. ‘Choose your enemies carefully, for that is who you become most like.” ( I think that is attributed to Nietzsche.)

@ Old Man, speak plainly. Away with these vague paraphrases, of vague persons, who you vaguely remember.

The quote:

“He who fights monsters should see to it that he himself does not become a monster. And if you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.”

— Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

There is no preconditional “if” that can erase an exMormon’s prior existence as Mormon. All former Mormons were Mormon. Many still are- culturally at least. Why wouldn’t they be? Learned behaviour is difficult to break.

The social transmission of a cultural group’s practices/ideas, from one generation to another, is an *essential* detail that cannot be responsibly forgone from any discussion of the phenomenon you speak.

Nietzsche’s quote however doesn’t include such detail, because Nietzsche wasn’t, specifically via the phrase, addressing religious/irreligious conflict between generations.

In short: 1) read Nietzsche before you use Nietzsche, and 2) consider more the processes you are describing.

Are relationships between the variables discussed really what they appear to be at first glance? Or is there something deeper going on like an intervening variable that might better explain the relationship?

Angela C:

“It’s a fun trick to substitute ‘obeying God’ for ‘obeying church rules.'”

Among the many ways that the commandment to love God with all of our heart, might, mind, and strength may try us is the inevitable question that every Latter-day Saint must wrestle with regarding our degree of participation in the His church.

Old Man (or his friend): “Ex-Mormons define themselves as being ex-Mormons. What they don’t realize is that they are so adamantly opposed to Mormon things that they are as fundamentalist in their thinking as a modern LDS fundamentalist or polygamist, just in a different way. Their cognitive bias just screams at you.”

Baha’is say this too!

https://bahai-library.com/momen_marginality_apostasy

Anon,

As a parent of children who have chosen to leave the church, you really nail the experience in your comments.

For me the central part of the gospel is being in relationship with God and other people (love God, love your neighbor). For me, love is listening to another’s experience. So yes, for me to be Christ like I do have to listen to the experience of my children.

I choose to respect their agency and to consider why they make that choice as you did. I have no respect for failing to listen and connect with a person, in order to express perfect loyalty to an institution. Picking the institution over my child seems absolutely contrary to everything taught by Christ. I pick Christ and I follow him by loving my neighbor which absolutely includes my children.

I also love the institution and community. But, yes, like you I have had to wonder if our involvement in the church has been for the better or worse for my children. It’s turned out to be a complex question.

No Dude, that was not the quote I was recalling.

If you wish me to be less vague, I will. First, an extreme example of a real-world conflict. The Israelis justified their war on Hamas due to the horrific attack on October 7th, an attack that resulted in the death, injury and hostage taking. But in rooting out an embedded terrorist organization, the have had to engage in actions with an enormous amount of collateral damage and they themselves have engaged in direct actions that will certainly sear the consciences of their soldiers. There is no joy in warfare. There is little personal freedom in military combat.

The same is true when one engages in ideological or cultural battles. The minute you identify an enemy, whether it be an ideology, person or group, you do damage to yourself in that you place limitations on how kind you can be and who you can love, because the welfare of the person you have identified as an enemy must be secondary to winning, right? That is not freedom. Jesus commanded us to love our enemies. If one loves an enemy, is he truly an enemy any longer? Can you mock someone you love?

What I have noticed (and my older friend attempted to articulate) was that many ex-LDS carry an enormous amount of baggage because they are at war with themselves, the church, their family, etc. And yes, many active LDS friends and family are going to be less than helpful. But the kindest thing we can tell them is to stop fighting. And I know that doing that is about the hardest thing for a human being to do. We are hardwired to fight and compete. Perhaps a dose of Buddhism, Stoicism or CBT may help. But moving beyond the fight is good for both sides, and they owe it to themselves.

In any religion we get covenants, commandments, organizational rules, traditions, suggestions, and strong opinions.

Only the first two on the list fall under the umbrella of “Obeying God’s rules.” but I feel there’s a tendency in the LDS church to put all of the items in that category – especially when they come out of the mouth of the Q15 and other leaders. This is, in part, because of the hierarchal and authoritarian leadership structure in the church. Also, many people interpret the temple’s “covenant of obedience” as broadly as possible.

Organizational rules are important – The church is a very large organization, and there needs to be structure, systems, and procedures to keep it running as efficiently as possible. They also get used to maintain the power of existing leadership. Fighting and reforming unfair organizational rules may be viewed as rebellion against the existing leadership, but it’s not disobedience to God.

Traditions give a sense of community and identity. Some traditions are good, some are harmless, some are bad. “Obedience” and “rebellion” are weird words for traditions, but playing along generally helps you be included in the group. Opposing/changing the harmful ones is not disobedience to God, but might alienate you from the community.

Suggestions are just advice from people – the advice may be good or bad. Obedience doesn’t apply here in the slightest, use your best judgment. The Word of Wisdom used to fall in this category. However, leaders have since rolled all sorts of suggestions and opinions into it and shoved it into the commandment/covenant category. These are often combined with the next category.

Strong opinions should be the least binding in terms of obedience, but they can be seriously problematic. Firstly, the strong opinions of authoritarian leaders are often touted as commandments. Powerful leaders will do things like change organizational rules or write/rewrite non-canonical materials to support their strong opinions. We’ll hear phrases like “follow the prophet” in an attempt to shoehorn opinions into the “commandment/covenant” zone. I think this is primarily where we see unrighteous dominion rear its ugly head; those are the instances where we must exercise good judgment and need strong, independent thinkers who aren’t afraid to “rebel.”

Old Man writes “But the kindest thing we can tell them is to stop fighting.”

Disagree. The kindest thing we can tell them is that we are here to help them process their trauma, whatever that looks like. It took me years to process and I’m extremely humbled that I had people who validated me during that time rather then shaming me for being upset.

Also comparing the Israeli conflict to a handful of post-Mormon subreddit threads seems unfair.

Old Man,

Hard to move on when the Church sends missionaries to knock on my door every other month.

Or that I can’t even go to a family members funeral without getting some stranger preaching to me about how Mormonism is essential to get to heaven (thanks Packer for that one).

Believe me, I wish I could ignore Mormonism entirely, but that would require me to get a new job and move (since I currently live and work in Utah), and probably disassociate from most of my family (since they are Mormon). Many of us are stuck having to deal with Mormonism and do just fine. In fact, most of the exmormons I know walk on eggshells around Mormons since it is so easy to trigger Mormons (just saying that you used to be Mormon tends to trigger alarm bells in their minds, which is how the Church likes it)

@Old Man,

And yet you remain no less clear, and as others have said, are making a gross comparison that does not describe the status nor degree of the relationship between Mormons and former Mormons.

How are you defining the word ‘ideology’?

In some posts you (mis-categorize IMO) religion as ideology- such as when you attempted to use Nietzsche earlier, and implicate Mormonism as being the the thing exmormons cannot seem to avoid replicating.

(You never specified the quote btw)

Other times you distinguish religion as distinct from ideology, even using one as an example as a way to move ‘beyond the fight’.

I fear however that you make the mistake of implying all conflict against a hegemonic framework of ideas and values as somehow harmful and bad.

I do not have enemies- but I do have opponents. I strive in my opposition to keep proportionality in mind, and try to not cause equal nor greater discomfort than that which I am responding to, nor what is necessary to create a more just society.

Conflict can be tempered but it will always exist to a greater or lesser degree. It is odd to ‘tsk tsk’ those most marginalized, and exiled by the powerful, for resisting the systems that create such harm.

Most expansions of civil rights and equality so far have not come about without the complaint and discomfort of those whose relative privileges were diminished.

We can be commensurate. We must consider long term avenues and consequences for greater peace. We can defeat opponents via our creation of more just institutions and norms.

But how can we live in a free and just society if we cannot provide space for those critical of these institutions and norms, and who face discrimination for this criticism incommensurate to the rebel’s means and ends?

Apathy is death.

@ Zla’od,

Thx for sharing that article! After reading the publication’s link and commentary, I was able to find the article’s rebuttal.

Click to access stausberg_challenging_apostasy.pdf

I ?think we are on the same page in noting that ‘counter-counter-culture’ proponents rarely question enough the politics of the majority, enfranchised, and the culturally normative relative to their critique of the ‘Otherly’.

Are you saying we need to think for ourselves?

Israelis who criticize the scholarship failures made by the Reshonim (950 -1400 CE).

The study by means of בנין אב/precedents, it opens a person’s eyes how the different mesechtot of Gemara interweave together; how the Mishna of one mesechta intermeshes with the language of other Mishnaot.

This makes the study of the Talmud as the Primary, and the study of the Reshonim rabbinic commentaries – secondary. Rabbinic Judaism errs because it reverses the Primary/secondary relationship, just as these rabbis fail to understand how the Gemara makes a משנה תורה\re-interpretation of the k’vanna of the language of its Mishna.

The boot licking brown-nose “Psycophant” behavior & scholarship practiced by Auchronim Talmudic “scholars” toward the Reshonim, whom the latter worships the opinions of the former, like gods placed upon a pedestal.

Their disgraceful טיפש פשט(bird brained) of ירידות הדורות qualifies as a National Jewish scandal. Perhaps the best example of this P’sycophat’ behavior: the RABaD’s statute law criticism of the Rambam’s statute halachic perversion.

His “criticism”, it compares to counterfeit money printed illegally, then laundered by other criminals; something like criminals bringing stolen goods to a pawn-shop. The impact of his “criticism” had a direct impact upon Rosh ben Asher, author of the Tur statute halachic perversion of the Talmud.

Another example of the distortion of learning the Torah & Talmud into box-thinking assimilated statute codifications, the impact that the Rambam’s Sefer-Ha’Mitzvot made upon the scholarship of the French Baali-Tosafot S’mag, and later upon the sefer ha-Chinuch.

These latter Reshonim altogether abandoned Rabbi Akiva’s chiddush (unique teachings) which defines Torah sh’baal peh (Oral Torah) as פרדס. The sefer baal ha’turim ha’shalem his grasp of רמז (hint) totally distorted. Wherein he limited this key concept of פרדס kabbalah to the numerical value of words. The ignorance of ben Asher, his failure to bind רמז together with פשט to interpret Aggadah, its משנה תורה on prophetic mussar from NaCH sources – an utter disgrace to the Jewish people.

These errors by key Reshonim “influencers”, the destruction to משנה תורה Oral Torah scholarship, far surpasses the error made by the false messiahs of Sabbatai Zevi, and Yaacov Frank. The errors made by the latter directly influenced the rise of Reform Judaism after Napoleon up-rooted the Catholic church war-crimes as established by the 3 Century Ghetto illegal imprisonment of Western European Jewry.

Errors in scholarship not limited to the Jews. It amazes me that Jews can readily see the termite-like corruption within the catholic church and Luthern protestantism. But fails to weigh and consider that this same termite-like rot within the wood “furniture” of Judaism!

A terrible matter for a Talmumic scholar of fame to make a gross error in scholarship. But far worse for down-stream scholars of reputation to equally fail to correct the errors made by earlier generations by scholars of great reputation. This latter error directly resembles the perversions of the false messiah movements in Yiddishkeit, secretly influenced by the new testament abomination counterfeit messiah belief system.

The Torah defines faith as: צדק צדק תרדוף (justice justice pursue).

Not chasing after some obtuse belief system of theology like the Xtian Trinity or strict Monotheism of the Muslim “church”. Justice: a lawyer never interrogates a witness by asking: “””What do you personally believe?”””

The scholarship of משנה תורה\common law/ as different from assimilated Roman statute law as the pursuit of justice to make fair restitution of damages inflicted upon others – from faith as defined as a personal belief in Gods. The Rambam’s 13 principles of faith, never once mentions the pursuit of justice!

This collapse of understanding the משנה תורה of Talmudic scholarship, wherein the Talmud serves as the model for a restored Israeli common law lateral Federal court system, when Jews return and & reconquer our Homelands, directly responsible for the Orthodox gross distortion – its condemnation of Zionism in the 1920’s and ’30s.

When scholars of reputation make fundamental errors in scholarship, this “action” compares to a stone hitting the tranquil waters of a pond. Impossible to stop the ensuing ripple effect. Hence another metaphor for ירידות הדורות – ripple effect. The latter describes: ‘domino effect’ precisely.

Herein concludes my introduction to the two בנין אב precedents of עירובין to our Gemara of .ברכות ט. The Reshonim scholarship failed to lead Israel out of g’lut. Post Shoah scholarship needs to ask the fundamental and most basic of questions: Why did the Reshonim fail to lead Israel out of g’lut.

If we cowardly refuse to hold our shepherd-scholars to account, even as we conquer Canaan, the threat of g’lut returning, it hangs over our heads like an ax to a Turkey on Thanksgiving.

No justice No faith. Just that simple. Theological constructs which attempt to dictate how man MUST believe in God …. utter drivel bull shit. Israel demands the return of all Oct 7th stolen hostages. Jabber of Cease-Fire or 2 State solutions, equal bull shit as a theological dictate to believe in this or that or some other Gods.

The Israeli Art of War: The intellectual effort to explode the “Ethical Containment Force” of a corrupt abusive civilization.

The Arab Spring directly threatened the culture/customs of Arab and Muslim, and even impacted Xtian moral consciousness of western civilizations.

The Apostle Paul, a Jewish agent provocateur sent to Rome to shatter the “ethical containment force” of polytheistic Rome, prior to the out-break of the Jewish revolt which sought to expel the Romans from Judea. Paul sought to promote a revolutionary Monotheism within Roman society which worshipped Ceasar as the ‘Son of God’.

For example: the shattering of the “Ethical Containment Force” of revolutionary France, Bolshevik Russia, the Nazi revolution which cast the Weimar Republic upon the dung heaps of history, and the Iranian revolution which did the same to the Shah of Iran. All these examples serve to define the theoretical concept framed as: “shattering the ethical containment force” that maintains an Order of a society prior to the outbreak of internal revolutions which over-throw the Old Order. And attempt to replace it with the revolutions’ idea of the “New World Order”.

In all these Cases of internal revolution of a society, the “Ethical Containment Force” imploded upon itself. Both the establishment “moral authority” & the corrupt Central Government destroyed. Like the Bolsheviks executed the family of the Czar.

The post-revolutionary fall of a targeted government likewise chaos and anarchy erupt almost immediately thereafter. Less than a decade after the Nazis seized power a general war ensued. The threat of this revolution caused a violent counter-reaction among other countries; much like a glass full of water that breaks consequent to falling upon the floor.

Leon Troskii called this social anarchy: “The continuous revolution”. Once political revolution collapses the reign of an oppressive government, this revolution spreads to other neighbouring corrupt governments, as expressed through genocidal international wars. The Iran Iraq war witnessed the deaths of millions of Sunni vs Shiite Muslims after the fall of the Shah of Iran.

No Universal God lives. The portrayal of belief in a Universal God, an example of false-prophets. Monotheism לא לשמה flagrantly rapes the 2nd Sinai commandment. The 10 plagues judged the Gods of Egypt just as the Armies of Israel judged the Gods of Canaan. The UN whore of the pre-WWII defunct League of Nations, tits on a boar hog. Prophets command mussar…they do NOT predict the future.

Israeli National Independence in 1948 NOT a Genesis creation story. Belief in dead gods, just a different form of gospels revisionist history that perverted Mankind till the Shoah. G’lut Jews abandoned the wisdom to obey משנה תורה\common law לשמה.

The תרי”ג commandments כלל, inclusive of all the halachic mitzvot in the whole of Talmud and Midrashim; the B’hag & Rashi פרט, ruled the lights of shabbat and visiting the sick – mitzvot דאורייתא. Purim: the Torah commandment not to assimilate and intermarry with Goyim. Removal of חמץ to up-root avoda zarah from the hearts of Israel.

The תרי”ג commandments NOT mitzvot organized into a positive/negative egg-crate carton. To observe shabbat requires the הבדלה which separates מלאכה from עבודה. To daven tefillat kre’a shma requires the k’vanna to duplicate the oaths sworn by the Avot. Hence the p’suk holds 3 Divine Names and requires both tefillin & tallit tzitzit.

Tohor time-oriented commandments NOT restricted to watching the clock. But arouse the fear of heaven כלל to dedicate a tohor middah to confront a national crisis. פרט Moshiach does NOT build a catholic cathedral but restores the cities of refuge, small Sanhedrin Federal courtrooms of the Torah Constitutional Republic. Faith defined: justice, justice pursue.

Purim defines the mitzva of the eternal war against Amelek. The curse of antisemitism expressed throughout the generations consequent to Jewish worship of avoda zarah in violation of the 2nd Sinai commandment.

To comprehend the k’vanna which the Siddur requires most significantly involves linking the Talmud to re-interpreting the k’vanna of the language of the Siddur like as and similar to how the Gemara re-interprets the language of the Mishna.

Purim linked to Pesach. Why? The removal of חמץ teaches a משל\נמשל mussar instruction. The נמשל to remove avoda zarah from within our hearts. Purim linked to Pesach. The megillah commands the mussar not to A) assimilate and walk within the customs, cultures, and mannerisms of the Goyim and B) not to intermarry with Goyim who reject the revelation of the Torah at Sinai.

The 2nd Sinai commandment: Do not worship other Gods. The megillah of Esther serves as a most authoritative “Gemara explanation of its Mishna”, how the Holy Writings of the NaCH serve as a commentary to the Books of the NaCH prophets.

Herein understands the common law\משנה תורה connection which connects the scholarship of the NaCH on the Torah and the later scholarship of the Gemara on the common law Case/Din Mishna.

The Gemara of mesechta ברכות, rabbi Yochannon ruled: a blessing requires שם ומלכות. Interesting the שם revealed in the 1st Sinai commandment turned into a Golden Calf translations which perverts the Divine Spirit Name that the lips of Man can neither frame nor pronounce to words like YHWH Yaweh Jehovah Allah and all similar “Golden Calves” on par with the Trinity avoda zarah.

Interesting too that church revisionist history fails to grasp the metaphor מלכות\kingship refers to tohor middot. That church revisionist history fails to grasp that tohor do not correctly translate as “pure” or “clean”. These word mistranslations fail to convey that tohor revers to distinct Divine Spirits – based upon the Name revelation within the 1st Sinai commandment which the Xtian revisionist history bible translations pervert into the “Golden Calf” of Lord and later JeZeus as God.

Returning to the “blessing” of the Cohonim. A tohor time-oriented commandment which requires k’vanna. This unique type of Torah commandment stands upon the foundation/יסוד of “fear of heaven/baal shem tov. A man through foolishness, greed, evil eye, can destroy his good name reputation which has taken a lifetime to build and establish in a second. Much like a balloon quickly pops when released about a field of cactus.

ברכת כהנים lacks שם ומלכות. The prayers of Tehillem/Psalms too likewise lack שם ומלכות. This begs the famous question which the Talmud continuously asks: מאי נפקא מינא/What’s the difference? Specifically in this particular case, between a blessing ie Shemone Esrei and kre’a shama, and tefillah – all of which equally lack שם ומלכות, from a praise – as in the prayers of Tehillem/Psalms?

Keeping the mitzva of Shabbat absolutely requires making a הבדלה which differentiates between איסור מלאכה from איסור עבודה. A person who keeps shabbat, like as if he kept all the Torah commandments. Why? Because observance of all Torah commandments likewise requires making this most essential מאי נפקא מינא\הבדלה which discern a “flat” 2 dimensional commandment unto a living “depth” 3 dimensional commandment.

Try to explain how the Book of Vayikra – not a barbeque to heaven? Next, address how the Shemone Esrei replaces korbanot when a korban requires a וידוי and the Shemone Esrei does not include the language of a וידוי. The 3rd Middle Blessing סלח לנו not the language of a וידוי because a person permitted to add a rabbinic וידוי in the last of the middle blessings שמע קולינו.

Lastly, please address the מאי נפקא מינא between a וידוי דרבנן which does not exist in the עצם language of the Shemone Esrei from a וידוי דאורייתא, which explains why the B’hag ruled, at the shock of the Rambam – despite the Rambam ruling that tefillah qualifies as a mitzva from the Torah (5th positive commandment in that egg-crate codification of commandments), tefillah משמע י”ח ברכות, a mitzva from the Torah.

Orthodox Judaism FAQ • Answers to frequently asked questions on Judaism

Why do Jews not believe in JeZeus even after all he did; and he said if you don’t believe in me you’ll go to Hell for eternity. Did Jesus lie? Is Gehinnom eternal? Do Jews not believe what he says? Why for 2000+ years have the Jewish people abhorred and decried belief in JeZeus as a false messiah avoda zarah?

New Testament theology = revisionist history. However T’nach does not teach history, despite historical/conservative Judaism narishkeit. The T’NaCH defines prophesy as a tohor persons who commands mussar.

Witchcraft, by stark contrast, a tumah false prophet predicts the future. Hence the New Testament (Roman counterfeit) declares that JeZeus fulfilled the words of the prophets. Proof that the New Testament promotes false prophet theologies. False prophet theologies defined as a predetermined creed/dogma which dictates what and how people should believe in God as an act of faith.

The Torah defines the tohor concept of faith as: Justice, Justice pursue. Based upon the cruel corrupt and oppressive Courts of king Par’o who withheld straw to Israelite slaves and who ordered the overseers to beat without mercy Israelites for their failure to meet the quota of bricks imposed upon these Israelite slaves. Based upon the conditions where Par’o supplied the Hebrews with the straw they required to make bricks their quota of bricks.

Yitro commanded a strong mussar to Moshe when he saw Moshe all alone judge the disputes between the people. Justice defined as the power of common law courtrooms to make fair restitution of damages inflicted upon Jews by other Jews.

Muhammad pulled the exact same rabbit out of his tumah magic-hat. The Koran rhetoric repeats prophet, prophet, prophet Ad infinitum, yet never defines – from the Torah – the term prophet. The Gospels did the exact same tumah Abracadabra, with the ((to quote Baba Kama: “Mountain hanging by a hair”)), the Pie in the Sky term of: Love.

T’NaCH prophets command mussar. Why? Because mussar applies straight across the board to all generations of bnai brit Israel. A bnai brit Israel grows the תוכחה\mussar rebuke within our hearts.

We grow and nurture this mussar within us. And these “tohor spirits” (based upon the revelation of the שם השם לשמה) they live within our hearts. They cause bnai brit Israel to dedicate defined tohor middot (‘ה’ ה’ אל רחום וחנון וכו, also known as the Oral Torah revelation at Horev) in all our future social interactions with our family, neighbours & people.

Hence the spirituality known as: the baali t’shuva. Mesechta Sanhedrin of the Talmud learns the mitzva of Moshiach tied to the mitzva of baali t’shuva. Based upon Moshe and the burning bush confrontation. Wherein Moshe vocally opposed to go down unto Egypt to bring Israel out from judicial oppression slavery. Yet Moshe, as a baali t’shuva descended unto Egypt and brought Israel unto freedom. Moshe serves as the Torah model for the mitzva of Moshiach. Moshe did not build a Catholic assimilated Cathedral as did king Shlomo. King Shlomo worshipped avoda zarah.

Moshe struggled to build the small sanhedrin Federal courts on the far side of the Jordan river. When king David, based upon the mussar commanded by the prophet Natan, commanded his son Shlomo to build the Beit HaMikdash, he had no such k’vanna for king Shlomo to assimilate and copy the customs manners and ways of the Goyim, who reject the revelation of the Torah at Sinai, and who build Cathedral Temples throughout the annuls of Human History. The k’vanna of the Moshiach to build the Beis HaMikdash learns from Moshe Rabbeinu who established the small Sanhedrin Federal Courtrooms in 3 of the Cities of Refuge on the other side of the Jordan river.

The mitzva of Moshiach constitutes as a tohor time oriented commandment; applicable to all generations of the Jewish people, just like tefillah stands in the stead of korbanot. All tohor time oriented commandments, applicable to all the Jewish people. All tohor time oriented commandments stand upon the foundation\יסוד of “fear of Heaven”.

This foundation of pursuit of judicial justice requires that a baali t’shuva dedicates a tohor middah. Which tohor middah does the mitzva of Moshiach require as its holy defining dedication to שם השם לשמה? The middah dedication to restore the lateral Sanhedrin Federal common law courts across the Torah Constitutional Republic.

The oath sworn alliance, known as “brit”, (like as found in בראשית\ברית אש, ראש בית, ב’ ראשית), this key Torah term means “alliance” and also “Republic”. The 12 Tribes forged this oath brit alliance which established the First Commonwealth of the Torah Constitutional Republic of the 12 Tribes. Based upon the Torah precedent, (known in Hebrew as בנין אב) upon Moshe anointing Aaron and his House as Moshiach.

Aaron dedicates korbanot. A korban sacrifice does not at all represent a barbeque unto Heaven. To dedicate a korban requires swearing a Torah oath. Just as to cut a brit לשם השם לשמה requires swearing a Torah oath. Just as the Shemone Esrei standing tefillah requires the k’vanna to swear a Torah oath through the dedication of one or more defined tohor middot.

The mitzva of Moshiach, a mitzva applicable to all generations of Israel. Just as tefillah and the mitzva of shabbat applicable to all generations of Israel.

The revisionist history of Xtian avoda zarah lacks the wisdom to discern between T’NaCH/Talmudic common law from Roman statute law. This tumah avoda zarah has witnessed oppression and cruelty that far surpasses the evil ways of Par’o and the Egyptians. This false prophet false messiah based religion proves the Gospel declaration of: “By their fruits you shall know them.”

The church stands guilty of the Shoah blood of Caine: Inquisition, 3 Century ghetto war crimes, annual blood libel slanders etc etc etc.

The power of the kabbala taught by Rabbi Akiva to raise rabbinic mitzvot unto mitzvot from the Torah.

Orthodox Judaism FAQ • Answers to frequently asked questions on Judaism

To keep shabbat requires knowledge how to distinguish shabbat from the week day. This discerning in the language of Hebrew “הבדלה”. The Torah commands not to work. Translations hides a multitude of sins. The word “work” expressed as מלאכה: skilled labor and עבודה: unskilled labor. The bible translations “broad brush” of “work” conceals this subtle distinction. The Talmud studies how different languages say the same thing. Examine the Targum Onkelos and witness a masterpiece by which a scholar makes a Hebrew/Aramaic 1:1 translation.

The study of this Targum assists all generations of “down stream” pupils to learn the Aramaic employed by the Talmud Bavli. Aramaic employs the clause: “מאי נפקא מינא”, which asks the question: “What’s the differerence”. The study of the Torah commandments, all 613 Torah commandments, most essentially requires making this מאי נפקא מינא which transforms positive & negative commandments – which do not require k’vanna; to tohor time oriented commandments, which do require k’vanna.

Why do Jews not believe in JeZeus even after all he did; and he said if you don’t believe in me you’ll go to Hell for eternity. Did Jesus lie? Is Gehinnom eternal? Do Jews not believe what he says? Why for 2000+ years have the Jewish people abhorred and decried belief in JeZeus as a false messiah avoda zarah?

New Testament theology = revisionist history. However T’nach does not teach history, despite historical/conservative Judaism narishkeit. The T’NaCH defines prophesy as a tohor persons who commands mussar.

Witchcraft, by stark contrast, a tumah false prophet predicts the future. Hence the New Testament (Roman counterfeit) declares that JeZeus fulfilled the words of the prophets. Proof that the New Testament promotes false prophet theologies. False prophet theologies defined as a predetermined creed/dogma which dictates what and how people should believe in God as an act of faith.

The Torah defines the tohor concept of faith as: Justice, Justice pursue. Based upon the cruel corrupt and oppressive Courts of king Par’o who withheld straw to Israelite slaves and who ordered the overseers to beat without mercy Israelites for their failure to meet the quota of bricks imposed upon these Israelite slaves. Based upon the conditions where Par’o supplied the Hebrews with the straw they required to make bricks their quota of bricks.

Yitro commanded a strong mussar to Moshe when he saw Moshe all alone judge the disputes between the people. Justice defined as the power of common law courtrooms to make fair restitution of damages inflicted upon Jews by other Jews.

Muhammad pulled the exact same rabbit out of his tumah magic-hat. The Koran rhetoric repeats prophet, prophet, prophet Ad infinitum, yet never defines – from the Torah – the term prophet. The Gospels did the exact same tumah Abracadabra, with the ((to quote Baba Kama: “Mountain hanging by a hair”)), the Pie in the Sky term of: Love.

T’NaCH prophets command mussar. Why? Because mussar applies straight across the board to all generations of bnai brit Israel. A bnai brit Israel grows the תוכחה\mussar rebuke within our hearts.

We grow and nurture this mussar within us. And these “tohor spirits” (based upon the revelation of the שם השם לשמה) they live within our hearts. They cause bnai brit Israel to dedicate defined tohor middot (‘ה’ ה’ אל רחום וחנון וכו, also known as the Oral Torah revelation at Horev) in all our future social interactions with our family, neighbours & people.

Hence the spirituality known as: the baali t’shuva. Mesechta Sanhedrin of the Talmud learns the mitzva of Moshiach tied to the mitzva of baali t’shuva. Based upon Moshe and the burning bush confrontation. Wherein Moshe vocally opposed to go down unto Egypt to bring Israel out from judicial oppression slavery. Yet Moshe, as a baali t’shuva descended unto Egypt and brought Israel unto freedom. Moshe serves as the Torah model for the mitzva of Moshiach. Moshe did not build a Catholic assimilated Cathedral as did king Shlomo. King Shlomo worshipped avoda zarah.

Moshe struggled to build the small sanhedrin Federal courts on the far side of the Jordan river. When king David, based upon the mussar commanded by the prophet Natan, commanded his son Shlomo to build the Beit HaMikdash, he had no such k’vanna for king Shlomo to assimilate and copy the customs manners and ways of the Goyim, who reject the revelation of the Torah at Sinai, and who build Cathedral Temples throughout the annuls of Human History. The k’vanna of the Moshiach to build the Beis HaMikdash learns from Moshe Rabbeinu who established the small Sanhedrin Federal Courtrooms in 3 of the Cities of Refuge on the other side of the Jordan river.

The mitzva of Moshiach constitutes as a tohor time oriented commandment; applicable to all generations of the Jewish people, just like tefillah stands in the stead of korbanot. All tohor time oriented commandments, applicable to all the Jewish people. All tohor time oriented commandments stand upon the foundation\יסוד of “fear of Heaven”.

This foundation of pursuit of judicial justice requires that a baali t’shuva dedicates a tohor middah. Which tohor middah does the mitzva of Moshiach require as its holy defining dedication to שם השם לשמה? The middah dedication to restore the lateral Sanhedrin Federal common law courts across the Torah Constitutional Republic.

No ‘religious fetishization’ of how the Sages of the Talmud interpreted judicial common law? If so then the question thrown back at you: the difference between Statute Law from Common Law? Among the Jewish people, the T’NaCH Talmud, a strong cultural masoret, practiced among and between Jews.

Roman Statute Law = assimilated avoda zarah. Kapos: too, an example of avodah zarah. Why? Because they “convert” to cultures and customs practiced by the dominant Goyim majority. Therefore how does the logic format in Jewish common-law differ from the logic schematics which defines and separates Roman statute-law, from Jewish common-law?

Many Traditional Jews chose to follow the path of defined as: ritual religiousism. Such ritual religiousism Jews view: Jews who follow the path of Talmudic common law – which requires פרדס logic – a very tiny minority know anything about – that this ‘tiny voice’ a Bat Kol from Heaven? No. Torah comes from within our hearts.

Muhammad declared that an Angel dictated the Koran. Angels by this bi-polar perverse theology come from the bi-polor Heaven/Hell paradigm.

The sages of the Talmud emphatically rejected this theological premise of Aristotelian logic. Torah comes from the Earth and not the Heavens. פרדס logic distinct and apart from ancient Greek logic philosophical formats. Track-n’-field a completely different Sports skills acquired. Long distance runners require completely different skill sets from the one to the other Track-n’-field sports combats.

Torah learns from the Earth and NOT the Heavens. Torah commands Mussar NOT History. A distinction of Depth that many blind thereto. The theology of Historical/Conservative Judaism confuses History with Mussar. The Talmud often teaches: How to logically think RATHER than what to logically think. Mussar requires the wisdom knowledge how to logically think. Church theological dogmatism-creeds: command what a person believes as true.

T’NaCH/Talmud common law (also known as משנה תורה) usually, or at least frequently, learns by comparing similar cases – the one to the other. This type of logic, completely different from the Ancient Greek mathematical syllogism deductive logic (If the premise wrong, then the conclusion reached – likewise wrong.) completely and totally different from Rabbi Akiva’s פרדס logic format system.

The Torah k’vanna mitzva of lighting the lights of Hannukka, to learn Torah using the פרדס logic system and totally rejects the ancient Greek philosophical schools which perhaps achieved the ultimate elevation of thought … totally different from the revelation of the Oral Torah with the 13 tohor middot. The concept within the Talmud of רוח הקודש, means blowing the שם השם לשמה, like the case of blowing the Shofar. 3 + 13 + 3 tekea tr’uah, shvarim ———-———- קום ועושה/ שב ולא תעשה\ טהור זימן גרמא מצוות.

Mesechta קידושין teaches that tohor time oriented commandments as applicable to women qualifies as a רשות option. If women choose to place tefillen or read from a Sefer Torah these tahar time-oriented commandments come within the רשות of their Will. The NaCH kabbalah בנין אב precedents for this Talmudic ruling, the story of D’vora & Barack fighting together to defeat the Army of Sisera.

Another example which explains “all” tahar time-oriented Torah commandments, which “all” deal with some crisis – life or death – situations: the reading of the Megillah of Esther. The fast by Queen Hadassah. Where she chose to approach the king and plead for mercy for the Jewish people; to thwart the efforts of Haman and his attempt of genocide. Purim and Pesach share a “כרת-like” common denominator. Purim links to avoda zarah: which prohibits assimilation and intermarriage with Goyim. While Pesach links the removal of chametz which teaches the essential נמשל, the removal of avoda zarah from within our hearts, in order to accept the Torah without the av tumah avoda zarah – in our midst.

Counting the Omer, yet another prime example of the exact same tahar time-oriented commandment. The 42 letter Divine Name, known as אנא בכח, carries the k’vanna dedication to remove the Av tumah avoda zarah from within the bnai brit hearts who dedicate the tefillah oath known as Shemone Esrei.

The oath sworn alliance, known as “brit”, (like as found in בראשית\ברית אש, ראש בית, ב’ ראשית), this key Torah term means “alliance” and also “Republic”. The 12 Tribes forged this oath brit alliance which established the First Commonwealth of the Torah Constitutional Republic of the 12 Tribes. Based upon the Torah precedent, (known in Hebrew as בנין אב) upon Moshe anointing Aaron and his House as Moshiach.

Aaron dedicates korbanot. A korban sacrifice does not at all represent a ‘Barbeque unto Heaven’. To dedicate a korban absolutely requires swearing a Torah oath. Just as to cut a brit לשם השם לשמה requires swearing a Torah oath. Just as the Shemone Esrei standing tefillah requires the k’vanna to swear a Torah oath through the dedication of one or more defined tohor middot. Blessings contain שם ומלכות. The precondition required to swear a Torah oath.

The mitzva of Moshiach, a mitzva applicable to all generations of Israel. Just as tefillah and the mitzva of shabbat, and all other tahar time-oriented commandments, applicable to all generations of Israel. Swearing a false oath or public profanation of Shabbat, carry the din of – כרת. The din of כרת – a life or death crisis of faith. If a רשע refuses to give his ex-wife her ‘get’. A beit din can make a נידוי decree of כרת, and there after issue a ‘get’ and free that woman; permitting her to do the tahar time-oriented commandment of קידושין.

The revisionist history of Xtian avoda zarah lacks the wisdom to discern between T’NaCH/Talmudic common law from Roman statute law. This Av tumah avoda zarah has witnessed: oppression and cruelty, that far surpasses the evil ways of Par’o and the Egyptians. This false prophet, false messiah – based religion – proves the Gospel declaration of: “By their fruits you shall know them.”

The church stands guilty of the Shoah blood of Caine: the Inquisition, 3 Century ghetto war crimes, annual blood libel slanders, mass expulsion of Jewish refugee populations from virtually every European country etc etc etc. This Av tumah avoda zarah condemned by נידוי כרת decree, as expressed through the k’vanna of the 9th middle blessing, within the Shemone Esrei oath blessing. Swearing the Torah oath through the mitzva דרבנן of Shemone Esrei raises this tefilla to a tahar time-oriented oath commandments דאורייתא.

Tahar time-oriented mitzvot can include all the halachot contained within the defined mitzvot within the Talmud. The Oral Torah פרדס has the power to elevate rabbinic mitzvot to mitzvot from the Torah at the revelation at Sinai. Hence all tahar time-oriented commandments require the Oral Torah k’vanna learned through the פרדס logic kabbalah taught by rabbi Akiva.