Does belonging to the Church alter your personality fundamentally?

I’ve been reading Steve Hassan’s book about Cults and Mind Control. In his most recent edition of this decades-old exploration of cults, he has classified the Mormon Church as a destructive mind control cult. Whether this characterization is accurate or not is a matter of opinion, but his decision was based on many interviews with people who had left the Church. Other sects, including the Jehovah’s Witnesses, Seventh-day-Adventists, Apostolic Reformation churches, and several of the more fundamentalist Catholic groups have also been included in this classification. I’ve previously blogged about Hassan’s BITE model and how it might apply to the Church, but today I wanted to explore a more fundamental concept: the alteration of personal identity that Hassan identifies as one of the hallmarks of a destructive cult.

First, a caveat or two. I am not personally convinced that the Church is a destructive mind control cult, which is a pretty damning string of words. I do, however, see that there are some cult-like intentions among some leaders and some culty behaviors among some of the members, and IMO, the move toward authoritarian thinking seems to be increasing, not waning. The reason I’m not convinced is that there are varying degrees of “cultiness” as in the BITE model. There are varying degrees of control on members’ lives, how much obedience is required, psychological reach of the organization, and consequences for leaving. Generally speaking, I know a LOT of people who have left, probably more than I know who have not left at this point, and increasing all the time. Most of those individuals may have felt conflicted, but they were not hunted down by the organization or mistreated and abused as they left as might happen in some of the other churches classified as cults by Hassan; but these are differences of degree, not kind.

But, as this specific book points out, it’s not merely the consequences for leaving that make belonging to these groups different or potentially unhealthy in limiting one’s personal growth. It’s also how they alter one’s personality and identity, how conformity to the group’s norms overrides one’s own individuality and ability to choose. This is an aspect I’ll take a closer look at today.

Under the influence of mind control, a person’s authentic identity given at birth, and as later formed by family, education, friendships, and most importantly that person’s own free choices, becomes replaced with another identity, often one that they would not have chosen for themself without tremendous social pressure.

Steve Hassan

Several years ago, I was at dinner with a non-LDS (and non-religious) high school buddy who read my mission memoir. This is a person who knew me when I was not active in the Church and was not really interested in it. I was surprised he was reading my memoir since I really only wrote it to a Mormon audience. He said he couldn’t even recognize the person I was in the book. He found it shocking, like it was about a completely different person, not the “cool girl” full of anti-authoritarian attitudes that he knew as a teen. I was taken aback a little bit because within the context of a mission, I was still pretty anti-authoritarian, but the Overton window was certainly different. But, he was also right. I explored in the book how much the mission culture changed me, turning me into someone who (albeit briefly) steered into the culture of mission work, joining in the enthusiasm and competition, and even enforcing rules (not very successfully). Whether or not being in the Church altered my personality, being on a mission certainly did.

My other thought about his observation is that I grew up in a high school where I was the only church member in my grade, and only one of two in my entire high school. My Mormon life was kind of secret and separate. Nobody understood my religous upbringing, and Mormons were viewed very unfavorably by the other churches in that part of the country. I deliberately kept my social life mostly separate at school so I wouldn’t have to explain my restrictions and our house rules to others. I knew that I had multiple layers of identity. At school I was hiding my Mormon self. At Church I was hiding whatever impulses and traits I had that were not acceptable there. Who was I really? I wasn’t sure. That’s not just a Mormon thing; it’s also a coming of age thing. It’s also a characteristic of someone who has moved a lot, as I blogged about here.

Those unfortunate enough to be born to members of a destructive cult are deprived of a healthy psychological environment in which to mature optimally. That said, children are remarkably resilient and I have met many who described never completely “buying in” to the crazy beliefs and practices.

Steve Hassan

So what are “crazy beliefs and practices” as opposed to just normal religious life? Within Mormonism, this probably includes things like polygamy being OK, being intolerant of coffee, tea and alcohol (as opposed to just personally not drinking those things–many churches have prohibitions on alcohol, for example), justifying racist or homophobic views, leader worship, dressing inappropriately for climate due to “modesty” guidelines or garments, defending church policies even if we don’t agree with them, and policing the beliefs and actions of other church members for orthodoxy. Most of what is portrayed in Mormon scripture is probably no weirder than what’s in the Bible; it’s only “weird” in that it’s unique, but that doesn’t make it culty. To paraphrase Forrest Gump, “culty is as culty does.”

But this disconnect between personal belief and views we feel comfortable expressing in a Mormon context is where the erasure of our own personality comes in; it’s where the “cultiness” of replacing one’s own identity with a “Mormon identity” that conforms to social pressure manifests.

Family ties can enforce silence on disbelieving second-generation members. It is easier to go along with the cult than to express their true opinions.

Steve Hassan

While this can happen in families, it also happens in church meetings. In the Shangri-la of my memory (or is it my imagined past?) we had discussions in church that weren’t rote; we shared, authentically, our own experiences and ideas, not just the party line. But maybe that’s too rosy a picture of how it was. If so, it’s certainly become less acceptable the older I’ve gotten. Most lessons are a “call and response” format. Teachers ask the acceptable questions, and students answer with the expected and acceptable answers. Outside sources are forbidden, and the definition of what is an “outside source” continues to expand. Lesson content now largely consists of rehashing talks from living church leaders. We don’t want, and many don’t tolerate, any deviation from the (current) script. I used to enjoy saying something that was authentic and surprising; it was almost always well received. Perhaps it kept people on their toes and woke up one or two of them.

The essence of mind control is that it encourages dependence and conformity, and discourages autonomy and individuality.

Steve Hassan

A friend at BYU once asked me, in all seriousness, if I thought everyone would look the same in the Celestial Kingdom. Such a thought had never occurred to me! But his question wasn’t completely without merit. In the temple, people tended to look a lot alike. You could almost always spot Mormons out in public. Maybe total erasure of individuality was in fact the goal!

People are coerced into specific acts for self-preservation; then, once they have acted, their beliefs change to rationalize what they have done. But these beliefs are usually not well internalized. If and when the prisoner escapes their field of influence (and fear), they are usually able to throw off those beliefs.

Steve Hassan

OK, now let’s not go too far here, but if we tone that statement down, this is a pretty good description of what happens when you are a missionary. Every emotion is heightened. Your actions have dire consequences, you are told, eternal consequences for yourself and others. Your failure to follow a rule might result in someone else’s loss of salvation. Total obedience and conformity are required for your success. A mission is probably the peak cult-like experience in the church (perhaps not a surprise so many young people nowadays are saying “nah,” even leaving early from their missions), but a version of this experience exists as an adult who is just a regular member as well.

What are “acts of self-preservation” as described by Hassan? It’s really anything we do that we are convinced is necessary for our salvation that contradicts what we want to do or what we think we should do. Particularly if you act against your conscience, it is necessary for you (psychologically) to convince yourself that those actions were morally right. When we harm someone else, for example, it is necessary for us to believe that person deserved it. When we harm ourselves, it is (in a mind-splitting way) necessary for us to believe we deserved it; we do this through internalized shame or guilt. Missions are a great way to increase commitment, but so are callings and assignments. That commitment often goes hand in hand with internalized guilt or fear of social reprisal.

Perhaps the biggest problem faced by people who have left . . . is the disruption of their own authentic identity. There is a very good reason: they have lived for years inside an “artificial” identity given to them by the cult.

Steve Hassan

Someone on Twitter recently observed that meet ups with former mission companions felt like “trauma bonding,” which made me laugh because there was some truth to it. Trauma isn’t funny, but basically, those shared traumas are exactly what we talk about. Even in Romney’s recent biography Reckoning, a story of him soiling himself in public is included–former LDS missionaries chuckle in recognition at his humiliation while non-LDS people view the story with horror. Hassan’s observation about loss of identity being a crisis after one has left is exactly how I felt when I left my mission. I no longer knew what I wanted to wear, to do, to read, to study. I felt aimless without my rigorous “purpose-filled” schedule. Within about a month, I suddenly felt free, like I was becoming a real person again. I could do what I wanted, and I didn’t have to anguish over every little decision or spend my time in fruitless pursuit of something that was drilled in my head as imperative to the salvation of humankind. I could just watch a movie or go on a hike. I could waste my time or eat a pizza without anxiety. I could . . . be myself.

But that Mormon identity was still there, very justified in my mind, often overriding my real preferences and personality. Yet I still felt much freer than I had as a missionary. Perhaps that’s why missions are so effective. They teach us how to internalize guilt and to defend sometimes pointless or traumatic sacrifices under an exaggerated polemic of good and evil.

- Have you experienced this type of Mormon identity crisis?

- Has your identity changed, either after leaving the church or returning from a mission or leaving BYU?

- Do you identify with Hassan’s explanation of how identity can be taken over?

Discuss.

“Has your identity changed, either after leaving the church…?”

I hadn’t been back to church services since COVID hit, and basically attended the Halloween and Christmas parties solo with my children. This year, my eldest daughter and I participated in a stake-level service project, I took both children to the Halloween party, and my I attended church with my husband and children last week. There were a lot of people who are/were hopeful/assuming that these actions connect the dots to me returning to full-fledged activity.

Walking away from church participation had allowed me to analyze a few ways that “performing gender” expectations has impacted my personal identity, my marriage, and how I co-parent our children. I actually found a ton of inspiration and “ways of doing” that were effective and inclusive outside the church teachings/doctrine.

Even with all the verbal boundaries and care that I set about my participation (and even not attending a RS-centric meeting), I still felt like I was reverting to a “gender-performing” self rather then my personal self.

There’s a “my church is a religion, your church is a cult” vibe to discussions like this. So Hassan is a professional cult investigator (albeit with some academic credentials). For me, that puts him in the same camp as professional UFO investigators, professional astrologers, professional demonologists, etc. To a cult investigator, every organization is a cult. So color me skeptical.

Here’s a different question (staying within the cult paradigm for the moment): Is the Church becoming less culty? Reading “The Next Mormons” book, one thing we can say is that the next generation of Mormons is becoming a lot less culty. A lot of the things that make any culty Mormon list (coffee, garments, mission) are being quietly rejected by younger Mormons. Either the Church adapts and becomes less culty, or it starts losing more and more of its youth and starts shrinking in terms of active members (it probably already has in the US and Europe).

At some point, leadership might have to choose between retaining the remaining culty features of the Church and retaining the next generation of Mormons. Tough choice: growth or control. I think in the long run they’ll choose growth. Imagine a revelation to Church President Uchtdorf twelve years from now in which God proclaims His unhappiness that what was expressly labeled as “not by commandment or constraint” has been implemented as exactly that, and that henceforth “the Word of Wisdom” is just helpful suggestions.

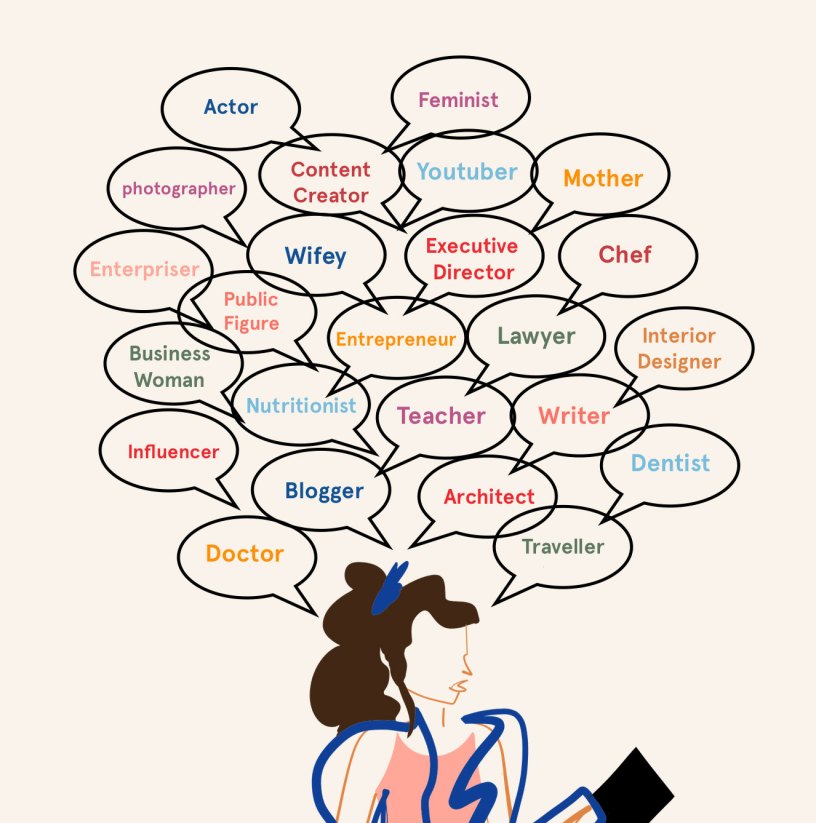

We are influenced and our personalities are shaped by everything, as he says: family, societal expectations, work culture, trauma, failures, disappointment, successes. To single our religion seems silly to me. Go listen to the America Ferrara speech from Barbie.

The practices of cults and religions could be drawn on a big Venn diagram – some things are clearly cult behavior, other things are clearly religious, and a bunch of things in the overlapping section could apply to both. I agree with you that it’s a stretch to categorize mainstream Mormonism as a cult under Hassan’s own model – some (but not all) fundamentalist groups fall pretty squarely in cult territory.

IMO Hassan tends to make the “Cult” circle a whole lot bigger than the “Religion” circle on his version of the Venn diagram – some of the things he lists as red flags in his BITE model made me roll my eyes. For example, under “thought control” he lists chanting, meditating, praying, singing, and humming as “thought-stopping techniques which shut down reality testing…” I guess they can be used that way, but at worst these things go into the list of similarities between cults & religions; not actual red flags.

(you can see his list if you google “Hassan BITE model” and click the first link).

I have certainly experienced a Mormon identity crisis. Interestingly, it was my mission (and the leadership of the MP specifically) that introduced a healthy dose of moderation to my Mormonism. The MP very bluntly told us in conferences not to be blinded by hyperfocus on strict rule-following at the expense of good judgment and personal revelation (“exceptions will happen, just don’t let exceptions turn into excuses for bad habits”). I do acknowledge that this isn’t the experience that many people have – authoritarian, hardline MPs are all too common.

My Mormon identity crisis has stemmed more from being at odds with the formal organization & leadership of the LDS church than from the core of the religion. I believe and hope there’s a loving God and that I truly can spend eternity with my family…I also hope (and believe) that it really isn’t tied to a covenant checklist and blind obedience to conservative old white men.

I can personally deal with the nuance, ignore the overbearing hardliners, and sift out the parts that I find positive…but am I able to adequately moderate the experience for my kids (daughters in particular)? Especially with someone like Oaks looming over the president’s chair? How can I siphon out the positive aspects of the community for them and counter the negative parts? (I don’t have answers to these questions, but I wrestle with them a lot)

My identity has changed a lot over the years. At this point in life, I’ve seen enough winters (literal and metaphorical) to understand just how hard it is to navigate through the world and life. It’s paradoxically made me both more jaded and more tolerant. We humans pretend to know a lot more than we do – Mormons are no exception. I used to say “I know” the church was true…I can’t honestly say “I know” anymore, but I do have a lot more hope in its place.

I’ve read Hassan’s book and come to the conclusion that I was raised in a cult. The thing is, I loved it, and it lead to great outcomes. So I don’t think it was a destructive cult, but a great cult.

I have a hard time reconciling this is my mind.

Previously, I felt compelled to obey (like I HAD TO obey) and it shaped many of my actions and personality. But the thing is, I recognize that many of the teachings and behaviors from my upbringing lead to great outcomes. I have a great life and I like the trajectory that I’m on, so I mostly want to keep living in the same way that I grew up.

The big difference is that now I no longer have these underlying beliefs about a prosperity gospel or being damned based on every little decision. I feel free to choose to do whatever I want to, it’s nice. But it turns out that making good decisions leads to good outcomes rather the church is true or not.

It may be a case of my personality lining up with church standards so it was just a good fit. Or it may be that I’m still under the church’s mind control even after deconstructing my beliefs and recognizing the cult mind control techniques the church uses.

I can’t figure it out, but it’s nice to be free from the pressure that I once felt to “obey and choose the right”.

Also, yes. As you probably guessed, I am a straight white male. And I realize that this had a big impact on why the church worked so well for me, but it does not work so well for others.

Was my identity wrapped up in Mormonism? Not 100% but definitely 51+%. And now? I’m really trying hard not to allow my identity get wrapped up in x-Mormonism. It’s easy to fall into that trap too.

All religions use some “cult tactics” because those are the things that make a community and a CULTure within the broader world. So, to outright reject that Mormonism is a cult means it isn’t a religion either. There is more overlap than there is difference between “harmful and controlling cult,” and “normal religion”, whatever a normal religion is. The Ten Commandments are controlling rules. A religion would fall apart and die f it had no “controlling cult traits” so Mormonism is successful because it is a controlling cult. But the word cult has gone astray of its roots, which meant religion, and has become synonymous with the Jim Jones koolaid drinkers. So, let’s not use that word.

Mormonism is a “high demand religion”. Joseph Smith even said something to the effect that a religion that has no power control its people, has no power to get them to Heaven. He was all in favor of having the people sacrifice a *lot* in order to be Mormon because he knew the more they sacrificed, the stronger their bond to the religion.

So, can we drop the dirty word and just call Mormonism a high demand religion? It is a high demand religion and that is what has made it a successful religion.

But back to the discussion questions. I don’t think my identity has changed that much as far as Mormonism goes. I never could make myself quite believe that God would pick a 14 year old boy as his prophet. Because let’s face it, 14 year old boys are still egotistical brats who are into mean teasing, cruel jokes, fart jokes, and …. yes, I had 14 y o big brothers …why do you ask?

I was disliked by the “in crowd” in my ward growing up, and even as an adult, always felt like I was not accepted. I knew many of the women disliked me because I was a military outsider when I was RS president. And back in Utah after hubby retired, I was just different than Utah Mormons. I had lived in other countries, seen much of Europe, been behind the iron curtain. Culturally, I was no longer an Utah native. I just always felt different if not disliked.

I never could shake my questions and problem with Joseph Smith. I just did not like the man. He triggered some kind of liar alert.

So, I was never all the way in and always saw myself as pretending to believe or giving up and going inactive. I went along with the culture because in Provo Utah there was no choice. Then as a military wife for 20 years and 14 major moves, the church was instant community and worth pretending. But I always knew that I didn’t quite believe but Mormonism was as good a place to worship Christ as any other and it was what I knew. I did try to make myself believe, but never quite got there. There were just too many issues with everything Joseph Smith added to Christianity. And Christianity itself had issues.

So, my identity has always been one of questioning and not fitting in. It didn’t help that I saw the difference between how the church treated males compared to females. I fit into the church best when I hated myself as a female. And of course having been sexually abused and seeing how the church loved my abuser so much more than it loved me, just compounded the whole thing.

So, when I officially gave up and stopped any pretense of belief, it wasn’t a huge change. Mostly I was able to love myself and let go of the concept of God loving his sons but not his daughters. So, it was a big improvement to my mental health, but not much change to my self identity.

Sorry this is so long, but it helped me to analyze it.

Ditto Josh h.

I prefer the term “wrong demand religion” but YMMV =)

I really dislike one aspect of this post. The word “cult” has been misapplied for so long that it has little value in intelligent conversation. Many social scientists no longer use it. Scholars of religion avoid it. The only times it seems to appear is in relation to radicalized descriptions of religious or political institutions one finds objectionable. Can we adopt a vocabulary more reflective of careful thought? I think Anna’s “high demand” is a start.

Interesting questions. I sort of agree with what some folks have said about using other words than “cult”; on the other hand, “high demand religion” seems like it could easily simply function as a euphemism for cult, so that term makes me a bit nervous as well (“We’re not a cult! We’re just a high demand religion!” seems like exactly what a cult would say). Putting aside the issue of terminology for a moment, when I was a more orthodox and orthoprax member, I definitely felt like my identity changed, but that was in large part due to the fact that I was baptized while I was at BYU, which is a highly charged atmosphere when it comes to Mormon identity, especially for new converts. Now that I’m PIMO, I feel like I’ve reverted back to my old self, a self with which I’m more comfortable and relaxed with than I was with my new-convert self.

And truth be told, I never really fit into any ward I was in anyway. I had an intellectual and authority-questioning bent even when I was younger, so that pretty much guaranteed I’d be viewed with suspicion by most true believers. I don’t mind it so much. I’m much happier now. And I feel like I’ve been able to take some of the best things that Mormons taught me about kindness, care, and true empathy and (obviously imperfectly) incorporate those things into the way I think and act. I suppose I’m with Pirate Priest a bit on this one; I’ve been around enough to know that life is hard for everyone, and even though I might still be tempted to be snarky or dismissive of true believers (of any religion, really), I do try to give most folks the benefit of the doubt and recognize that most of us are doing the best we can to get through life and try to find a little happiness. I definitely feel that I’ve outgrown the church, however. Not in an arrogant, “I know better than orthodox Mormons” way, just in terms of where my own journey has taken me. Music and writing and teaching just give me way more satisfaction than church does, so I gravitate towards those things and try to prioritize what’s really important to me and spend my time doing those things. I certainly don’t hate the church; I just don’t have any use for it these days.

I agree with the fact that Hassan’s use of the term “cult” is extremely broad (as I’ve indicated in all the posts I’ve done that reference his work. From the linked OP I did on the BITE model, I rated Mormonism (in my completely subjective experience) as follows:

Behavior Control – 4.5 out of 10

Information Control – 7 out of 9

Thought Control – 2 out of 8 (*I would rate it higher for missionaries)

Emotional Control – 6 out of 8

That would put Mormonism at 56% culty. Is that average for religions? Is the police department (which Hassan has also classified as a cult) more or less culty? What about a Trump rally? So, yes, I agree that these terms are fluid enough to be sorta meaningless, but so is a lot of discussion on psychology–so much is self-reported or subject to personal bias and blind spots. As a psychologist, Hassan also notes that individuals struggle to identify “cults” that they are involved with, and they can only see it in retrospect or see it in other groups that they don’t belong to. Well, fine, but that also makes me think that maybe that just means that a cult is not empirical, but subjective.

I think Anna’s use of the term “cult tactics” is useful. Do groups intentionally use manipulative means to control behavior, information, thoughts and emotions? Is control the objective or growth (because these are usually opposites)? I don’t think “high demand” solves the problem because all it does is hurt feelings less (no one wants to admit they belong to a cult, after all) and put a thumb on the scale for the organization rather than the individual (you, the individual, just couldn’t meet the “high standards” of the group). Hassan did an interview with John Dehlin that I didn’t find particularly persuasive overall, but the case for how much control was exerted was much stronger for missionaries. Former members are certainly going to be more likely to consider the organization a cult as they divest from it. Likewise, if you work for Pepsi for ten years, but you secretly prefer Coke, you’re going to feel a new sense of freedom while drinking Coke now that you aren’t selling the competing product.

I actually think the better term is “culture.” Our culture does modify our worldview and our identity in ways we seldom examine until we leave that culture. “Cults” emerge as smaller, more exclusive, maybe more secretive groups within a larger culture, but that describes every human organization we might join. The real issue is whether it encourages human flourishing and personal freedom to grow, or attempts to control and manipulate toward secret aims that are not disclosed and that we wouldn’t choose if we understood them. Many organizations aren’t what they seem. Many exploit. Many don’t fully disclose the costs up front. Are they all cults? Probably not. But they all contain cultures, and these cultures limit our identity when we join them.

I like using the term “culture” also. Especially for this particular discussion. I think the term we might apply is Mormon culture for general members and mission culture for missionaries. Then we can break down the tactics the church uses as to how controlling they are and which might be harmful.

Even though I consider myself totally out, I really cringe at things that unfairly criticize the church. I guess I still have more loyalty than I like. I think the church uses about the right amount of control, but then I never went on a mission. If the church could drop some of the shaming for normal sexual things, I think they would have a good balance. And the word “cult” is unfocused criticism in that it says “evil” without really telling people what is wrong.

The high demand is what ties people to it. So, I see that as a positive trait, not a negative. And it works really well for straight white males.

I just wish it considered all of God’s children as equals. But then I remember pulpit pounding about how blacks not having priesthood was unchanging doctrine, and it sickens me to see today how women still are not close to equal and how LGBT are unwelcome. And that’s all unchanging doctrine too.

I’m not super familiar with Hassan’s work, but it seems to me that he is playing fast and loose with terminology. Sure, there are times when I’ve felt like I’m in a cult – like when I’ve had to sit in in primary, and the kids are droning through “Follow the Prophet” – but I’ve felt the same way listening to Christian “praise” music on the radio. Doesn’t make either a “cult,” necessarily. Words get overused over time and lose their meaning. Just look at how the term “ghetto” has changed over time from its original historical meaning to now describe any perceived “subpar” neighborhood. The warning to not “drink the cool-aid,” which once referred to a very tragic event within a very real cult, is now thrown around as a casual warning not to buy into things such as workplace policies. Then again, I had a sociology professor at BYU-I who told the class that Mormonism qualifies as a cult by the academic definition (used in Sociology) of the term. And he’s still on the faculty. Take that BYU-I detractors.

The first part of this (not the last half):

“People are coerced into specific acts for self-preservation; then, once they have acted, their beliefs change to rationalize what they have done. But these beliefs are usually not well internalized. If and when the prisoner escapes their field of influence (and fear), they are usually able to throw off those beliefs.”

How it (or something similar) goes deeper than a mission, while having lifelong consequences is the LDS Church’s insistence (nearly) on marrying in the temple:

-daily choices we make so we will be worthy (to enter the temple, and of our future mate)

-who we date

-who we do not date

(particularly noticeable to non-lds high schoolers within the Jello belt)

-where we go to college

-our college major (r/t if one expects to be the bread winner for many, or the one who expects they will be provided for by another)

-who we marry

-if we marry

-our career choices (see college major, above)

-ability to recognize what love is (as long as that box is checked…)

If we marry impacts the women (men too, but fewer) who don’t marry. Part of the rationalization is adding, “in this life”.

In my observation, faithful lds women who have not married seldom become homeowners, Aunt becomes integral to their identity, some fantasize about why they didn’t meet “the one” in “this life”.

This phenomenon is on display when one of the “lucky ones” marries a widowed apostle, and her lifelong sacrifice is explained.

The COJCOLDS benefits directly from this. Less so, many followers.

Cults, culture . . . Time for a Mafalda comic strip.

https://stryptor.pages.dev/mafalda/04/234/

The mission: Resistance is futile. You will be assimilated. 😁

Scholars of New Religious Movements are divided on the c-word. Gordon Melton complains that “cult” just means “a religion I don’t like,” i.e. is inevitably subjective, and sees anti-cult groups as just a different kind of NRM. (“Sect” has a similar usage in Europe.) Others point to the practical reality that some religious groups are objectively dangerous, and come up with various criteria to try to distinguish them from regular religious groups. Some go by theology, leadership style, intensity of expected commitment, or separation from / hostility to the wider society (but…monks!). There are concerns over pressure and control, sex and money. As a practical matter there is a spectrum between, say, Scientology on one hand and your bog-standard Presby-lutherans on the other, with Mormons somewhere in the middle.

Josh h, I think the same. I tried interaction with the ex-Mormon community for a while only to find that it was full of kooks and crazies who exaggerated and insulted. I remember that my opinion of the ex-Mormon community declined dramatically when I once posted a plea on the ex-Mormon sub-reddit to stop comparing the Mormon church to North Korea because it was an insane and insulting exaggeration that gravely minimized the pain of victims of the repressive regime. And I mostly received pushback and anger to my post. I knew I had had enough. Some ex-Mormons are so consumed with anger and bitterness that they are incapable of talking about Mormonism in any rational and productive way.

The church consumed my identity from a young age. I would say I was definitely in a cult because my family was a sub-cult within the Mormon Church. My father is very controlling and rigid, and he was 100% dedicated to Mormonism and enforced that on the family. My mother completely supported him. Breaking out from under my father’s influence resulted in some horrible consequences, including feeling more uncomfortable at Church because Church just assumes kids need to forgive without considering what the parents actually did.

My personality has changed as I’ve gotten out from under my father’s thumb. In other ways, other aspects of my personality have just been uncovered by throwing off those Mormon shackles. It came with a sense of relief: “oh, that’s right, this is me, I don’t have to pretend to be someone else anymore.”

Whether or not the Mormon Church is a cult also depends on what your family was like. Laidback, casual parents may mean Mormonism is just a place to go on Sundays. Parents like mine meant the Church was a cult.