Today’s guest post is by frequent commenter Pirate Priest.

This is my second guest post here at W&T – I’m grateful to have been invited back. A few weeks ago Angela mentioned a funny experience while helping her ward organize a pioneer trek when some of her fellow leaders argued that the young women should wear a ridiculous number of layers just in case one of them tripped while trekking and gave some “poor” boy a glimpse of thigh. This got me thinking about funny stories from my own trek experiences but, more seriously, about why us Mormons do the trek experience at all. What lessons are so critical that we’re willing to drag kids (and ourselves) off into the desert dressed in more layers than actual pioneers?

There are, of course, the usual valuable lessons in faith and perseverance. But as I thought about it more deeply, there is a whole side of pioneer history that’s almost entirely overlooked but that holds very different, but equally important, lessons.

Trek

For any who aren’t familiar with Mormon pioneer treks (usually just referred to as “trek”), they are historical re-enactments of pioneers trekking across the United States to come to Utah. It’s similar to other types of historical re-enactments where participants will dress in period attire and try to get a taste of how it would have been to live through that time in history. The trek craze started in about 1997 with the Mormon Pioneer Sesquicentennial with many Treks being operated by the LDS church. Essentially leaders and youth drive to the middle of nowhere for a few days of handcart pulling, camping, and (hopefully) spiritual inspiration.

Pioneer treks were the new cool thing when I was a teen, so our leaders weren’t entirely sure how to help us prepare. It was a six-hour drive one way to get to Martin’s Cove. It was the peak of summer and the heat was unbearable before dressing like we’d stepped of a boat from Victorian England. The dust was suffocating, many of us felt compelled to be there, but we still tried to find a spiritual upside…at least until a pack of coyotes came through camp on the first night and ate most of our food. It was probably a bit more of an authentic experience than the leaders were hoping for.

Willie and Martin

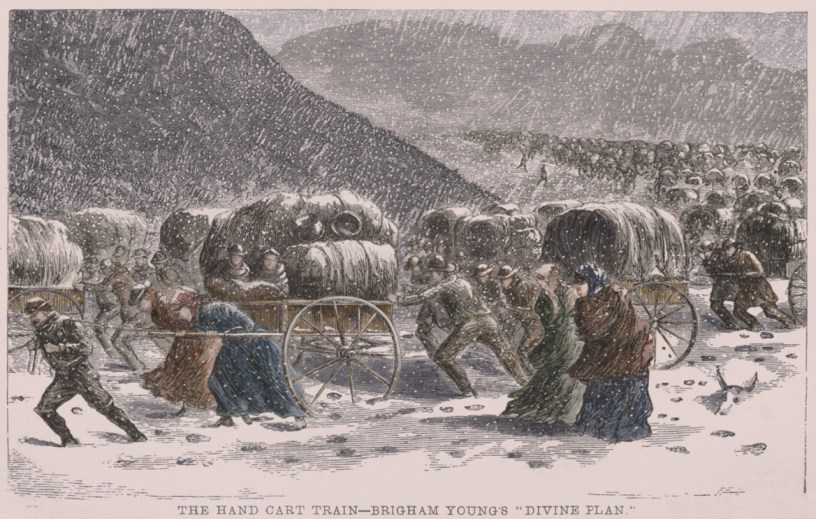

The handcart movement began in 1856 when Brigham Young sought a cheaper, faster way to move poor European converts to Utah. Converts would sail from England to New York or Boston, take a train as far west as possible, then begin pulling handcarts west. Despite the misery of hiking 1300 miles while pulling a 300-pound wheelbarrow, eight of the ten handcart treks went quite smoothly. There were some deaths and hardship, but overall their trips were relatively uneventful. For the fourth and fifth companies, however, it was a much different story.

The Willie and Martin companies arrived late from England when nobody was expecting them. Weeks passed as they scrambled to prepare for the journey, which pushed the timeline dangerously late in the season. A debate was held to decide whether they should continue the journey or wait until spring; the recent European emigrants deferred the decision to missionaries and church agents who were familiar with the crossing. One missionary, Levi Savage, argued that travelling at that time of year with a mixed company of women, young children, and the elderly would result in suffering, sickness, and death. All remaining church leaders said the companies should press on to Utah and that they’d be protected by divine intervention. Disaster ensued.

Before the’d left Nebraska many of the cattle used to pull the supply wagons were lost in a stampede, forcing each handcart to carry an extra 100 pounds of flour. When they reached Fort Laramie to restock their supplies, no supplies were available. In an attempt to speed their progress by lightening their load, the luggage allowance was cut by from 17 lbs to 10 lbs, leading the travellers to discard much-needed clothing and blankets. A blizzard then descended on the region, halting all progress while the pioneers were quickly freezing and starving to death.

Many a father pulled his cart, with his little children on it, until the day preceding his death.

John Chislett, survivor

George D. Grant, who headed the party dispatched to rescue the companies, gave this account:

…Imagine between five and six hundred men, women and children, worn down by drawing hand carts through snow and mud; fainting by the wayside; falling, chilled by the cold; children crying, their limbs stiffened by cold, their feet bleeding and some of them bare to snow and frost. The sight is almost too much for the stoutest of us; but we go on doing all we can, not doubting nor despairing.

George D. Grant

By the time the companies reached Salt Lake more than 214 had died, with countless more having fingers, toes, and limbs amputated due to frostbite.

Only about 5% of pioneers migrated in handcart companies, but their stories are ingrained as important Mormon symbols of faithfulness, sacrifice, and perseverance. We use phrases like, “faith in every footstep,” and “endure to the end.” Elder Bednar just spoke in conference about “they of the last wagon” – the quiet faithful at the back of the wagon train eating all the dust but still pressing on. Even “the covenant path” conjures images of pioneers faithfully trekking along the trail.

All these lessons are inspiring and important, but I’m found asking myself, why didn’t they just quit in Nebraska?

First, let’s look at another group of brave people facing death an dismemberment on an icy trail: adventurers climbing Mount Everest.

Into Thin Air

In March of 1996 members from three separate expeditions attempted to summit Mount Everest. A powerful storm descended onto the mountain during their climb, and the climbers battled hurricane-force winds, freezing temperatures, fatigue, and lack of oxygen as they fought to get safely down the mountain. In just 24 hours, eight climbers would die on the mountain, making the deadliest disaster on Everest until the 2014 avalanche. This is the story recounted by John Krakauer in his best-selling book Into Thin Air and the subsequent movie of the same name. As usual, we tend to focus on the story of heroic determination and grit in the face of icy death.

Krakauer’s book is riveting, but there’s another story from that same day on Mount Everest that rarely gets told. Three climbers were on the mountain that day whose names usually aren’t mentioned: Dr. Stuart Hutchison, Dr. John Taske, and Lou Kasischke.

The mountain was unusually crowded that day with three separate expeditions simultaneously attempting to reach the summit. Hutchinson, Taske, and Kasischke unluckily got stuck behind a large group of relatively inexperienced climbers who had clumped together making them difficult to pass. Before they’d left camp, expedition leaders had emphasized the importance of strictly observed turnaround times. Climbers attempting to summit Everest are are given a turnaround time; if climbers fail to reach the summit before the allotted time, they are to stop climbing and return to camp. The descent down Everest is much more difficult and technical than the ascent – climbers are eight times more likely to die coming down than when going up. The risk of a nighttime descent multiplies the danger of a deadly mistake, especially on the Southeast Ridge where a misstep can lead to a deadly 8000-foot fall on one side and a 12,000-foot fall down the other. Thus, turnaround times are used to keep an already-dangerous descent from becoming even more deadly.

After climbing for 12 straight hours and failing to pass the slower group, the trio debated about what to do. It was 11:30 am, the turnaround time was 1:00 pm, and an expedition leader had just told them it would be another three hours to the summit. The three climbers realized they would never reach the summit before the turnaround time and decided to cut their losses despite each of them having spent ~$70,000 to join the expedition. Hutchinson, Taske and Kasischke returned to camp without any complications and eventually left the mountain and returned home.

Not exactly the stuff of a Hollywood blockbuster, but I’m not sure their friends and family cared much about that.

Quit

This alternate story from that day on Everest was recounted by Annie Duke in her bookQuit. Duke was working on her PhD in psychology and was one month from

defending her dissertation when she quit academia to pursue a successful career as a professional poker player. She now combines her knowledge of psychology and poker to help people improve their decision making skills. Duke teaches that perseverance, while important, isn’t always a virtue, and that knowing when to quit is just as critical as having the grit to endure difficult situations. She teaches what Kenny Rogers’ song The Gambler has been trying to teach us for 45 years:

You’ve got to know when to hold ’em

Know when to fold ’em

Know when to walk away

And know when to run

Kenny Rogers, The Gambler

According to Duke, life is not like chess – there isn’t some perfect move that will win the game if we can just calculate correctly. Rather, life is like poker – it’s a combination of skill and luck. We need to learn to accept what we can’t control and adjust our choices to benefit us over the long term.

Let’s return to the pioneers: What would have happened if they had temporarily folded and simply waited for spring?

Just how we rarely remember Hutchinson, Taske, and Kasischke abandoning their Everest ascent to return safely home, we also rarely remember the ~100 pioneers who stayed in Nebraska and waited for warmer weather. These pioneers still made it to Salt Lake just a few months later, but (more importantly) arrived with their families and bodies intact. We often talk about the blessings associated with hardship, but I’m left asking which group of pioneers was the most “blessed” in this situation? Those who were starving and freezing in the wilderness while burying loved ones in shallow frozen graves? Or those who simply quit when the odds weren’t in their favor and resumed when the scales had rebalanced?

The lessons we learn

We as humans tend to focus on the heroic stories of grit and determination, and make movies about those who persevered. While perseverance and endurance are often virtuous and inspiring, they aren’t universally the right choice. We should also learn from those who quit wisely. We should learn the importance of perseverance from the pioneers, but we should also learn when and where to apply grit to our advantage.

Now I ask for your input:

- Is there a time when you persevered when it may have been wiser to quit and/or adjust course?

- When have you quit and realized it was the right (or wrong) decision? What other inspirational church stories might have a different valuable lesson hidden on the other side of the coin?

- How can we teach the youth to make good decisions about when to quit and when to persevere?

Disclaimer: Given the audience here at W&T, I’m sure the topic of quitting the church will come up. My purpose here is not to encourage others to follow suit or to judge those who have decided to take that path. Rather, I believe that we can learn from those around us, even if we may disagree or choose a different path.

Ahhh… the handcart disaster. Through our annual treks we demonstrate that unjustified hubris about the past is not solely a Texas trait (their reverence for the Alamo). And I say this as one having ancestors among the victims and the rescuers. Franklin D. Richards should have been excommunicated for homicide and extreme negligence.

Why do we find a need to reenact an incident when leaders misled members and caused such suffering? Because it has become a rite of passage for youth and for many a bit of ancestor worship. The “myth” of the handcart companies, a tale permeated with suffering and miracles (many miracles told on treks are the product of the film “17 Miracles,” which is largely fictional) is more potent than real history.

But what I really fear is more abstract. What message are we conveying? I know some LDS leaders who WANT the ability to send unwitting individuals off on paths of suffering… He who demands the most (sacrifice of all things) from members must be a great leader, right? IMO, Christ-like leaders alleviate suffering. They don’t cause it.

Thanks for this engaging and interesting post. The choices that are lauded are usually heralded as the best choices, but as you demonstrate, the best choices are often the ones that lead to far less drama. We just don’t hear about them, unfortunately. You ask good questions that have me thinking deeply an about my own answers.

My ancestors were in the Martin company. John and Mary Douglas brought their 2 children (each by a previous marriage) and both of them died coming to Utah. When they arrived in the valley Mary was 38 and worn out from hard living. They would have had no one to care for them in their old age. Mary wrote to her sister Matilda in England and encouraged her to come to Utah and marry John as 2nd wife. Matilda was a widow with several children. She came, and my ancestor was a child of Matilda raised by Mary as her own child.

Don’t worry, I could tell you a sad polygamy story from my ancestry too, but it would be off topic and unconnected to handcarts.

I was raised in Sweetwater county Wyoming where the greatest tragedies occurred in these hand cart companies. Winter in Wyoming will kill you if you are not prepared.

But I agree with the OP. There’s a time to change course. To put it in religious terms, our circumstances will change due to individual agency and choice (and not necessarily our own choice), and simply the physical realities of this world. A person can get new guidance and personal revelation at any time as to the best choice in moving forward. Staying the course and moving forward is one way to exercise faith, but not necessarily the right one. Staying the course can be a failure of clear thinking and a result of magical thinking.

Years ago my bishop asked my husband and I to visit his office. They had set it up with my husband who hadn’t even spoken to me. I was at the church already waiting for my boys who were in young men’s.

I had had conflict with my bishop before… When my husband told me we had this meeting set up I had a sudden foreboding or prompting so strong I doubled over like I had been punched in the stomach. I couldn’t go in the bishop’s office and I walked around the church to think about it. But of course I had been conditioned since I was a tiny girl to do whatever the bishop asked. So my husband and I went into his office. I should have said no and went home.

Once we were in his office he was angry at me as ward organist, because the chorister had told him I wouldn’t let her pick whatever songs she wanted as recommended in the handbook. I was a fledgling organist. This bishop never picked the sacrament meeting topic until Wednesday (5 days before church) at which time the chorister was informed. Then she would pray about the hymns and tell me. Five days wasn’t long enough for me to prepare the hymns (all the other organists had moved out of the ward in the 2008 recession). I needed at least 2 weeks to prepare the hymns but the chorister was unwilling to pick them until she knew the topic. I often had to tell her no about her choices, which she resented.

How the bishop spoke to me about this was inappropriately authoritarian and angry. My friend in the bishopric was there and later told me he was surprised by how the bishop acted and didn’t know what to do. My husband is very sensitive to conflict and actually blacked out and can’t remember what happened.

I have run over the scene over and over in my mind. If I had been there supporting a younger sister in this situation I would have stood up and encouraged her to come with me and leave the room. I should have stood up and left the room in my own defense. My husband or my friend should have helped me do this. But none of us had any weapons against the authority given to this bishop by the church (even though it was unrighteous dominion).

What I did do was tell the bishop to wave his handbook over the piano keys and see if they would play the songs the chorister picked. Then I told him that the chorister knew I couldn’t play the songs she picked with only 5 days preparation, so she had told the bishop this story to get him to plan sacrament meeting further in advance.

We left but I refused to talk to the bishop in his office for 3 years after that, even when he would ask.

I have rehearsed standing up and walking out over and over in my head since that day. Doing so can prevent further emotional injury, of every one involved. I have used the skill of standing up and walking out over and over since that day in multiple settings. Often, a change of course is absolutely the right thing to do.

Pirate, as you suggested, in addition to a story of quitting rarely being good material for a good Hollywood script, you’re never going to get this kind of advice from the Church simply because there is really no situation where the Church wants people to quit. Feeling overwhelmed by a calling? President Nelson would tell you to put down the cigarette and ice cream and turn to Heavenly Father for solace and don’t you dare ask for a release from the bishop or even address it with him. Somehow, God will magically make you feel less overwhelmed despite the circumstances not changing one iota. Having problems with the temple ceremony? It just means you need to attend the temple more, not less! And make sure you don’t read up too much about Masonic rituals. Feeling torn between having a good relationship with your children who struggle with Church policies for various reasons and being an “all in” member who vocally supports the Brethren? You better be all in. After all, this life is a mere nanosecond in comparison to eternity, and, if your lazy learner kids don’t turn things around, don’t worry, God will give you new and better children in the celestial kingdom.

Sure, you might here some lip service to the idea of not running faster than you have strength, but more often you hear about God strengthening us to bear the burdens He will place upon us and enable us to run just as fast as He needs us to. Even then, to do that, He might need you to abandon any hobbies or personal time you might have had and enjoyed. Gotta lighten the load somehow…

The only personal example I can think of where quitting was the right call is actually basketball, to include Church basketball. I’ve enjoyed playing basketball my entire life, and I was always a decent to good player. Unfortunately, God didn’t see fit to give me a knee that would hold up to the rigors of basketball as I got to my late 30s when I finally called it quits. I still miss playing, but that feeling is completely overwhelmed by the lack of pain I get to experience due to being smart enough to quit something I really enjoyed.

I had never heard about the 100 who stayed behind. Really changes the story around. I can think of 2 reasons why the 100 who stayed behind are never mentioned:

1. We love to focus on the inspirational sacrifice of those who suffered in the Willie and Martin handcart companies.

2. The 100 who stayed behind disobeyed Church leaders, and that is the biggest no-no in the Church, thus the church, and church histories never mention them.

If we told the story of the 100 who told the Church “no”, I wonder how that would change Church culture. I know for myself I was raised to never say “no” to the Church and I did not break out of that mindset until I left the Church. I would have probably had a healthier relationship with the Church if I was raised with the option to say “no”.

lws329,

Forgive me for straying out of my lane here, but you seem to be convinced that walking out of the bishop’s office would have been the better response. But if you had done that, the bishop would have been deprived of the useful information you provided him. It doesn’t matter if he didn’t act on that information. You improved the probability of your situation improving from zero to a positive number. Walking out would have left it at zero.

the family of president david o mckay was on the ship thorton that brought over most of the people in the willie and martin handcart companies. his father and grandfather stayed in the east for three years and worked before they saved enough to buy a wagon and ox team and travel to utah

I have ancestors who came across as part of the Willey handcart company. The family tradition was they had planned to wait in New York City that winter because they knew that they were too late in the year to make the crossing safely. The plan was to find lodgings and work in order to afford to purchase of the they rig needed to emigrate during the next year’s travel season. Needless to say that didn’t happen. As a side note, my ancestor, Lars Mortensen later married one of John D. Lee’s daughters Clarissa. So that means I have ancestral connections to both the hand cart disasters as well as the Mountain Meadows Massacre that occurred the next year. But the real question I have in relation to the Trek re-enactments is do the participants really understand what what those pioneers experienced, especially the cold, snow and the lack of food that the pioneers experienced. Both of my children participated in Trek and were well fed. I am not the only one who has questioned the real value of Trek.

I’m quite sure few in the LDS Church ever heard stories of the pioneers who trekked west, didn’t like what they found in the Salt Lake Valley, and trekked BACK to Iowa, where a good many of them eventually united with what became the Reorganization in the 1850s & 1860s. That “double trek” is one of the reasons there are so few Community of Christ (formerly RLDS) congregations in the Intermountain west even today.

The hymn, “Come, Come Ye Saints,” written during the difficult trek across Iowa from Nauvoo to Winter Quarters, even appeared in the RLDS hymnal (1956) because so many RLDS members had forebears who made that Iowa trek. Sadly, a prevailing anti-LDS sentiment in the church at the time led to a successful General Conference resolution to have the hymn removed.

@Rich Brown – I always love getting the CoC viewpoint on things – all the different voices of Mormonism are one of my favorite things about W&T. This is definitely not discussed on the LDS side. Making it to Utah, then disliking it enough to make the grueling trek back is a whole new level of both quit and grit.

@lws329 – I think that how you rehearsed standing up and walking out is important – it’s absolutely a skill that takes practice. It can be especially hard to do when there is a power differential (either real or perceived), and I think it’s even more difficult in a church context when we’re told to “sustain” and respect the leaders even though they might be completely out of line. That bishop was totally out of line, and it’s completely understandable that you’d refuse to meet with him again afterward.

In China, the hardships of the Long March are widely celebrated, commemorated and mythologized. But as far as I know, they don’t force teenagers to reenact it in period attire. Because that’s just dumb.

The example of the handcart pioneers is not just a cautionary tale of when it’s appropriate to quit something, but a warning to be wary of overzealous, manipulative, or spiritually abusive Church leaders, and be ready to stand up to them when they appear, and be willing to speak up on behalf of those in the group who are too afraid to speak for themselves.

Lastlemming, Great question.

While in principle I agree that it’s generally better to communicate than to remain silent, there were good reasons why I shouldn’t have continued trying at that point.

#1. The bishop was angry with the chorister at that point instead of me and never changed the timeframe he used in managing sacrament meeting. The sacrifice I made to speak had no positive outcome.

#2. This conversation occurred after a long line of difficult conversations with this bishop where I walked away feeling emotionally traumatized. I can’t recount it all to you without reliving that trauma. I was blamed by him for all my marital problems, for asking for accomodations for my special needs kids (which he rejected), and for conflicts in the primary presidency (I was 1st counselor). In one instance he read the handbook to our presidency, emphasizing following the primary president’s lead for 3 straight hours giving me all the eye contact. During the meeting I had a panic attack that lasted until 11 am the next day when, I finally took action and asked the RS president to release my visiting teacher. (She was the primary president who asked the bishop to set me straight on following her authority without discussion or question.)

While I forgive the total lack of skills this bishop has, protecting my mental health takes priority over helping him be a better bishop. My husband and I did share our experiences with our stake president. He was only interested in our bishop’s personal growth. I do think he improved by the end of the 5 plus years he served. However, at what price? I wasn’t the only woman (or man) in the ward traumatized by his heavy handed micromanagement.

For me entering his office was like an alcoholic entering the bar. There was only one outcome to be expected. I had to learn to protect myself by standing up and walking out, or not making appointments in the first place. I will never turn to my bishop as a person with authority over me again. That’s too emotionally dangerous. I have since taken great care to teach my children to regard their personal authority over their own actions as greater than any person’s authority over them. That’s a lot better for emotional health.

lws329: A few years ago when we had just moved to a new ward, I had previously been in the RS presidency and tasked with the activities which had beyond burned me out. So when they asked me to accept an assignment (not even a calling) to be on the new ward’s RS activities committee, I said I wanted to think about it. The next thing I knew, I got an email welcoming me to this committee I had not agree to be on, and the person who sent it said it was going to be made official in the next sac mtg. I was flummoxed. Since when does “I’ll think about it” mean “Yes! I’m down for whatever!” I texted the person who had asked me to do it and declined before that meeting, but it left a really bad taste in my mouth that this was necessary. I didn’t agree to it. It’s not even a real calling anyway. I had already expressed that I wasn’t into it. So WTF with the overstepping? Boundaries, people.

While this story was a memory that came up in response to your story, it’s also related to the post because there’s something about narratives that require personal sacrifice, even that is unnecessary to the point of death, and about lauding nonsensical hard things (Zion’s Camp, anyone?), but aside from lauding the sacrifice, it’s also a narrative designed to reinforce the blind obedience of the individuals who agree to these things, an unwillingness to advocate for oneself. It had apparently never occurred to this person that “I’ll think about it” meant that I was ACTUALLY going to think about it, and that “I’m not crazy about this request given hating doing activities for the last 3 years in my other calling” meant “Probably not.”

Great post Pirate!

The Martin Willie disaster gets the attention but otherwise the handcart migrations were successful and mostly uneventful. Trek as a reenactment of successful handcarting is a legitimate youth activity. I’ve supported several such Treks and give my approval. Over the years there has been a push to lessen the forced austerity and make the experience less about hardship and more about the group experience of sharing an outdoor activity without modern distractions. I approve of this.

There is no doubt that persistence in the face of struggle and opposition is a virtue. Easy quitting – giving up at the first sign of difficulty – can become a bad habit. However, the pursuit of hardship for the sake of being challenged is not praiseworthy. And embracing all hardship as good and desiring pain as proof of ones righteousness is simply wrong.

Those who survived the Martin / Willie disaster had a terrible experience that for some revealed the face of God. We can recognize this spiritual blessing without giving credit to any of the persons whose poor decisions created the disaster! In our own lives we need to be thoughtful of our pursuits and the cost and benefits of them. Likewise, we need to be aware of the burdens our decisions can have on others.

As I have aged in the church I have become much more willing to say “No”. In one case a calling was so demanding it was exacting a toll on my physical health. Of course the supervising leader said the Lord would help me endure. I answered, the Lord is telling me to quit.

Consequently, my rate of accepting callings has dropped from 100% to 25%. Not that I don’t want to serve in the church, but rather I have learned it is spiritually unhealthy to hope I can do a calling and make others happy by saying I will, when I will not actually enjoy doing the assignment (This rule also applies to work and volunteering).

One of the most important insights I ever made about myself is if I don’t care what makes me happy, no one else will care either. Learning how one can best serve others, and putting oneself in those positions to effectively serve can require saying no, and disappointing people.

A Disciple: “if I don’t care what makes me happy, no one else will care either.” Amen, bro. Menopause has taught me one thing, which is that I matter, and that if I’m not my own friend and advocate, if I don’t take my own interests to heart, nobody else will either. That’s probably why so many women who were burned as witches were menopausal (plus, their value to society was greatly diminished due to becoming infertile and husbands being ready to replace them with a younger model but that’s another story). It’s like a switch went off in my head saying “Enough of personal sacrifices, most of which inconvenience me and benefit nobody.”

“What other inspirational church stories might have a different valuable lesson hidden on the other side of the coin?” I can think of a few:

1. Tithing stories. For each “inspirational” tithing story told about how people chose to pay tithing over purchasing the necessities of life (food, rent, medicine, etc.) and were somehow miraculously saved by receiving a anonymous food delivery or envelope full of cash in the mailbox, there has to be thousands of stories of real people who made this choice and just suffered as a result. Most people who choose to pay tithing over buying food will simply go hungry.

2. Zions Camp. Zions Camp was a complete failure in that it did not complete the mission that Joseph Smith claimed God revealed to him to retake, by force, if necessary, the Church’s (and Church members’) lost lands in Missouri. 14 members of Zions Camp died while participating in the failed venture. Because of the utter failure to complete its mission that was supposedly revealed by God, apologists have written volumes on why Zions Camp should not be considered a failure. For example, they describe how many future Church leaders participated in Zions Camp, learned how to “obey”, etc. The fact remains, however, that Zions Camp failed to achieve its revealed objectives. I doubt the families of the 14 men who died considered it to be very successful, and many of the men who chose not to participate probably had few regrets when they heard of the afflictions that the Zions Camp members endured.

3. Dumping girlfriends with multiple earrings. There is Bednar’s infamous story of a couple who were dating (https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/liahona/2006/12/quick-to-observe?lang=eng). Apparently, the woman liked to wear multiple earrings. After hearing Hinckley’s talk on how women should only wear a single earring, the man dumped the woman when she failed to stop wearing multiple earrings. Of course, the man is the faithful hero in the story for not marrying a faithful enough woman. However, I consider the woman to be the true hero of the story for not giving in to unreasonable demands made by her boyfriend and her Church leaders. She probably ended up living a much happier life free from such a judgmental jerk.

“How can we teach the youth to make good decisions about when to quit and when to persevere?”

Every LGBTQ youth (well, this applies to adults, too) should be directly taught in Church that they should stop participating in the Church. They simply aren’t going to be happy and mentally healthy trying to live a celibate life in a Church that explicitly rejects them.

I also wholeheartedly agree with Jack Hughes. We should continue to teach the youth (and adults) about the failed handcart companies. However, instead of praising the faith of the Saints who chose to make the journey in the winter, we should instead praise Levi Savage and the Saints who chose to wait until spring. We should teach the youth that Franklin Richards, even though he was the presiding priesthood leader, was simply wrong, and the handcart companies suffered for blindly following his uninspired counsel to proceed in the face of the looming dangers of winter. Just as the Saints who listened to Levi Savage and waited until the spring were blessed with a safe passage over the mountains to Salt Lake City, members will be blessed for ignoring/disobeying today’s Church leaders when they teach things that violate their own values or personal revelation.

@A Disciple: yeah I’ll agree that a trek as a shared experience in the outdoors with a pioneer theme is something I could get behind. Back when they were new, it seemed to be much more about making those pesky youths appreciate how easy they have it. I haven’t been involved in trek in a long time, so I’m glad to hear it’s evolved. You’re right that there’s this false sense that suffering=blessings when many times it’s just suffering. There’s that half-joke in Mormonism that you should never pray for patience or humility because God will happily beat you down…that whole idea is ludicrous. You can rise to meet your challenges and become stronger, but God doesn’t “bless” people with needless hardship…especially when it can be entirely avoided.

@Angela: It’s funny how there’s an automatic assumption that people will accept every assignment or calling. In a conversation I had with my brother years ago about overbearing church callings, he said, “You know…you can just say ‘no’ right?” It seems so simple, but there’s this dogma that “God will never give you more than you can bear” so you just take on literally everything thrown your way. If you feel like taking on a new challenge out of your normal wheelhouse, great! If not, it’s ok too.

@Mountain Climber: Zion’s Camp was such a disaster It’s odd how such a pointless, futile thing produced so many of the early church leaders. I think you may be right about LGBTQ youth – I’ve had the pleasure to personally meet Tom Christofferson, the brother of Elder D. Todd Christofferson. Tom is openly gay and has spent time both in and out of the church as a result. I met him shortly after PoX was announced. I remember him saying that the LGBTQ members would just have to decide whether or not the church was working for them at that time, and if they left that they could still live happy, fulfilled lives while the church sorts itself out. Tom had re-joined the LDS church at that point and said it was working for him, but said he was also very happy as a non-Mormon. With an Elder Oaks looming over the President’s chair, I think many LGBTQ members and supporters will have to make some hard decisions about what’s working for them.

Faith is not believing in ourselves when we follow the counsel of our leaders or our peers. Faith is believing in things that are true, and counsel from leaders sometimes is not true. Therefore, one must discern for oneself. Jesus gave two short parables that teach this concept in Luke 14. In the first, He asked, “For which of you, intending to build a tower, sitteth not down first, and counteth the cost, whether he have sufficient to finish it?” The second: “What king, going to make war against another king, sitteth not down first, and consulteth whether he be able with ten thousand to meet him that cometh with twenty thousand?” We can have great faith when the counsel comes from the Lord. For the Willie and Martin handcart companies, the counsel from the Lord was not to start after a certain date. They confused their enthusiasm for faith, and they began to build a tower without resources, or they began a war without enough soldiers. To exercise faith here would have been to wait until spring. Faith in stupidity or pride or enthusiasm is not faith in Christ, even when people make the decision in a group and an apostle (Elder Richards) blesses the group decision. I regret the loss of life on these two handcart companies, but I think that we should teach the right and example of Levi Savage and those who exercised faith by remaining behind until the spring. Brother Savage may not have been aware of these two parables, but he lived by them. He and those who remained behind with him had great faith in Jesus Christ. We usually ignore them, but if we were to mention them I think we would say that they lacked faith because they did not trust in God. They had great faith in the Lord, and that is why they remained behind and started their journey in the spring.

Several things come to mind here:

D&C 10:4 “Do not run faster or labor more than you have strength and means provided to enable you to translate; but be diligent unto the end.”

So often we portray Joseph Smith as being super human, yet the Lord counseled him with this.

Next, who was the 19th Century Church Leader, who abandoned his Mission in the Far East, due to it being unsuccessful?

mountainclimber479: The Tithing stories also skip over the number of members that have needed to use Bishop’s Storehouse food. I believe in Tithing, but some members feel that financial shortfalls are caused by not doing their Tithing “right”. Yes, I had a member of my Ward tell me that, during a financial struggle our family had.

Just a point of clarification. Levi Savage did not wait behind until spring, he went with the companies. Having some experience on the trail he opposed going. “When hearing of Savage’s opposition in Iowa City, Richards called a meeting and openly rebuked Savage for his lack of faith and for not following his leaders.” Levi Savage decided to follow his leaders and said “Brethren and sisters, what I have said I know to be true, but seeing you are to go forward, I will go with you, will help you all I can, will work with you, will rest with you, will suffer with you, and if necessary I will die with you. May God have mercy bless and preserve us.”

You can read more information about Levi Savage and the Willie and Martin Handcart companies here: https://graceforgrace.com/2009/03/23/levi-savage-a-true-disciple-of-jesus-and-hero-of-the-willie-handcart-tragedy/

Great post! And a really good discussion.

A decision that I am glad that I didn’t delay is my decision to get divorced. You can imagine that no one, not priesthood leader or extended family member, approved of my decision to get divorced after less than five years of marriage. I knew it was the right thing to do, and the right timing. Divorce is always hard. But the stories I’ve heard of what it’s like to end a marriage after 20 or 25 years sound a lot worse than what I had to go through. By ending the marriage sooner, I avoided a lot of damage. My XH and I are friendly and we’ve been able to avoid drama and put the kids first. Also, the reasons that led to the divorce are all still there. He didn’t change. I can deal with it better at a distance, and I’ve changed so I can handle problems with more maturity, but he did not change. I remember talking to a church sister in a marriage with similar problems, and she was worrying about regretting a divorce if things because maybe things would get better in 15 years. I don’t know what she decided to do, but I’m so glad that I didn’t wait 15 years to find out if things would have gotten better.

Great post Pirate – I’ve often felt these types of youth experiences to be emotionally manipulated but it could be that I have a tendency to be cynical.

The post reminded me of my own family’s surprising pioneer connection while working on my family history. I came to the church via my mother’s conversion to the church in England so never expected to have any pioneer connections. One time I clicked on another contributor who had added some sources on my line. After a bit of digging and reading some pieces in the memories section on FamilySearch I find that the cousin’s family of a paternal 4th grandfather emigrated to join the saints in 1857. Tales of great trials along the way, grueling lengthy sea voyage to New Orleans, several dying after arriving from cholera etc. Then sent by BY down to settle in difficult conditions near Cedar City. One lad working 4 years with no shoes. It was most interesting but made me wonder if it was all they expected when leaving their homes?

Not that it matters to anyone, but not 1857 but 1854

@Janey: It sounds like you made the right decision in not delaying given your circumstances in the situation. This is a point that Annie Duke discusses in her book – it’s easy to fall into that trap of escalating commitment, and quitting sooner is often much less costly than waiting. She has a lot of practical tools for overcoming or working around those pesky cognitive biases to make better decisions about when to quit or persevere.

@Mike H.: I think you’re right about Joseph Smith being painted as a sort of folk superhero – this happens with a lot of early church leaders…and even current leaders. The truth is that they were just as human and mortal as any one of us. I think the hubris of Elder Richards and the other leaders left them with a lot of blood on their hands. I think a serious part of the problem is that church leadership continues to teach that it’s not possible to be led astray by following the Q15…it’s been taught since the early days of the church. When a prophet is doing prophet things he’s infallible…and if a mistake was made, then he (conveniently) either wasn’t actually in prophet mode or God had a change of mind. Either way, if we just blindly follow the prophet we’ll be eternally blessed for it even if the prophet was somehow wrong. This sort of thinking has killed a lot of people throughout history.

Regarding tithing, it’s a whole topic of its own. It has morphed from a very reasonable request for members to help the church get out of dire financial straits, but has morphed into a monstrous sense of entitlement. It’s bizarre that a verse or two from a very minor Old Testament prophet is given more weight that the words of Paul in 2 Corinthians where he said that people should donate voluntarily without needing to feel reluctant or compelled. Or even LDS prophets like Joseph F. Smith saying he’d love to be see tithing replaced with voluntary donations within his lifetime…he said that in 1907.

Ironically it was bankers raking in money on the backs of the poor to (supposedly) support the temple that led to Jesus personally cleansing the temple in Jerusalem. Church leaders have publicly said the church doesn’t need the money, but you still have to pay if you want those celestial kingdom ordinances (otherwise, have fun waiting outside until someone who DOES pay tithing gets those ordinances done for you after you die). At what point should we expect Jesus to show up in one of these newly-announced temples with a “scourge of small cords” and turn over some tables?

I loved the story of the 3 who turned back at Everest. A similar story that always sticks with me is the account of Ernest Shackleton in the quest for the South Pole. Before Amundsen and before Scott made it to the South Pole, Shackleton came excruciatingly close to the pole in one of his expeditions. His small party was less than 100 miles from the pole, but supplies were dwindling and their return would not be guaranteed He had spent fortunes of time, money, and suffering to reach that goal, but remarkably turned back and remarked upon his return that his family would better appreciate a live donkey than a dead lion. We celebrate Shackleton’s grit and leadership for his later adventures with the sinking of the Endurance, but turning back was a remarkable choice too.

I’m not sure what practical lessons each of us can take from the Everest/Shackleton/Martin Company stories, but certainly it gives one something to think about. Thanks for a great post!

@squidloverfat: that story about Shackleton is another fantastic example. This makes me admire Shackleton even more. There’s no questioning is skill and grit as an explorer or leader (every member of his crew survived), but he also didn’t let his own hubris prevent him from making the wise choice on that earlier voyage.

I think the practical application is that we can all improve our decision making skills. This includes choosing when to grind and when to walk away (at least in the short term). We need to be aware of common mental traps (escalating commitment, sunk cost fallacy, leaning too much on authority, etc.) and learn practical skills how to mitigate them. Grit matters, but we should try to persist at the right things and avoid needless suffering.

I think that the common themes that suffering=blessings and that persistence is universally a virtue can lead to unnecessary hardship.