“In mem’ry of the broken”[1]

“At various times Karras longed to have lived with Christ: to have seen him; to have touched him; to have probed his eyes. Ah my God, let me see you! Let me know! Come in dreams!

The yearning consumed him.

He sat at the desk now with pen above paper. Perhaps it wasn’t time that had silenced the Provincial. Perhaps he understood, Karras thought, that finally faith was a matter of love.”

The Exorcist, by William Peter Blatty

I remember the first time I watched The Exorcist. When I witnessed what Father Karras does at the end of the film to get the demon out of the possessed girl, my jaw dropped. Right out of scripture, I understood it immediately. It was frightening and violent, but heroic too. It floored me to realize this horror flick was actually a powerful Christian tale. I felt as well-taught as I have ever felt in any seminary class.

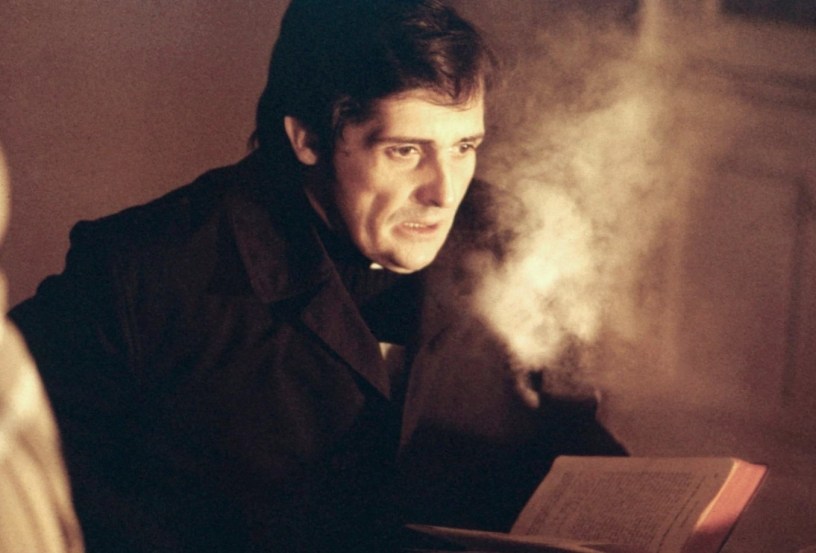

You see, the main character of The Exorcist is not the possessed girl. It’s not even the titular character, an old priest named Father Merrin. The protagonist—the character who must change for the plot to resolve—is Damien Karras. The plot hinges on the choices of this young priest going through a personal faith crisis.

In the movie, it is very clear what Father Karras does to save the girl and cast out the demon. In the novel, as I have just discovered on a first reading, there is a sense of tragedy about it. I actually teared up reading it. In the book, no one understands what Karras did to free the possessed girl. Though, that only underscores the significance of his victory over darkness.

Father Karras is an example of true Christian discipleship. He is my hero.

“An anguished moan escaped Karras’s lips as he bowed his head above the Host. He struck his breast as if it were the years that he wanted to turn back as he murmured, ‘Domine, non sum dignus. Say but the word and my soul shall be healed.’

Against all reason, against all knowledge, he prayed there was Someone to hear his prayer.

He did not think so.”

“Actually, The Exorcist has become an Easter movie for me.”

It was about 11pm, when I said this to a Registered Nurse at her workstation on the second floor of the hospital. Except for the nursing staff and housekeepers like me, the whole building had fallen into a dimly lit trance. The nursing staff are spread thin and always preoccupied with the sick and dying; I’m so grateful when they spare me a moment for small talk. When I confessed to this RN—a fellow bookworm—how my annual Easter movie was not The Ten Commandments, but rather a classic horror film, she broke into an ear-to-ear grin. She seemed slightly creeped out but in a fun way. She scrunched her nose and said, “Really?!”

“Well, yeah,” I said, grinning back at her. “I mean, it makes sense if you do Lent, and I mean really do Lent: 40 days of abstinence, church attendance, and Christian contemplation. When you arrive at Holy Week, on Saturday night the Catholic Church does this spooky Easter Vigil Mass. They turn off the lights and make you sit in the dark for half an hour, as the priest reads scripture by candlelight.”

“Yeah!” the RN said, nodding enthusiastically. Now she was following me.

I continued, “I get to the end of that vigil mass and say to myself, ‘I wanna go home and watch The Exorcist. I mean, horror genre trappings aside, it is a masterpiece! And it’s a consummate tale of spiritual victory over darkness.”

“We’re just a poor little family of wandering souls. By the way, you don’t blame us for being here, do you? After all, we have no place to go. No home.”

The demon, speaking to Father Karras through its host, the young girl Regan

The thing about being cast out, speaking as a special witness—as one who knows, and not by faith—well… let me explain it with an exercise. In your mind, picture the human in this world who loves you the most—someone who loves you unconditionally. This is probably going to be a parent or spouse, but it could also be a full-grown child you are hoping will look after you in your old age. In your mind, clearly see this dear soul looking into your eyes with all the love you know they have for you.

Are you picturing them? … Good.

Now, imagine saying something to them you think is funny. Imagine telling them a joke you regard as irreverent but harmless, all the while looking directly into their eyes. Notice their expression change to disapproval. They do not find your joke funny. It offends them.

As the loved one looks into your eyes, their disapproving expression becomes more intense. You feel a distinct impression they want you to leave the room. This person, who until a moment ago loved you unconditionally, now places an absolute condition on their love. In fact, you no longer feel any love from them at all. Unmistakably, they want you to leave and stay gone forever.

Incidentally, this is why demons, once successfully cast out, tend not to return to that host. As it turns out, sons of perdition have a just a little bit of self-respect. Not much. But enough so that, once cast out, they move on.

That is what it feels like to be the object of exorcism. It is the experience of looking into the eyes of the most beloved person in your world and realizing, with horror, that you have found the limit of their love—a point beyond which there is no love left to give. Wouldn’t you leave then? I did.

“…I think the demon’s target is not the possessed; it is us … the observers … every person in this house. And I think—I think the point is to make us despair; to reject our own humanity, Damien: to see ourselves as ultimately bestial, vile and putrescent; without dignity; ugly; unworthy. And there lies the heart of it, perhaps: in unworthiness. For I think belief in God is not a matter of reason at all; I think it finally is a matter of love: of accepting the possibility that God could ever love us.”

Father Merrin, the Exorcist

Notes and Discussion Questions

Thank you for reading. This post was prompted by my first reading of the novel The Exorcist. The film adaptation has been a favorite of mine for many years. If you have seen or read The Exorcist, what was your experience with the story? What did or didn’t you care for, and why? How does the story relate to your sense of real-life struggle between the mind’s sense of good and evil? Your comments on this post are welcome below.

[1] The lyric “In mem’ry of the broken…” comes from the hymn “How Great the Wisdom and the Love,” #195 in the green hymnal of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It served as my soundtrack while writing this post.

This resonates with me. The word ‘unworthy’ was very common when I was LDS. Black or white – worthy or unworthy. I think Satan has a great influence on church leaders through the door of arrogance (we are the elect leaders who don’t apologize). The light of God never goes out based on my learning of grace. In a performance-based church like LDS, it’s very easy for the light to go out. Based on my years of learning in the field of organizational leadership, the Pygmalion Effect holds true – how we see people affects them deeply over time. I’ve read many stories of people who have experienced church courts and heard a story just last week of a high-counsel member who left after sitting in on one. You leave feeling no dignity, Many leave in despair, rejecting themselves in shame, which is the worst feeling to have if you want to break the bad behavior that got you into the court. Ironically, feeling unworthy to start with, and having even more unworthiness piled on during the court, this would be the optimal time to show the grace of Christ; to show love to the one who feels undeserving of it. To show the true Christ, not the LDS legalistic version that only forgives when behavior is corrected and a man judges the sinner to be worthy. The more I learn about grace and the infinite love of Christ (from other religions), the more I see clearly the distorted and inconsistent views of grace. When guys like Brad Wilcox have to explain grace and it’s not coming in a unified manner from the top 15, there is a major problem.

Part of being agnostic for some of us is not really knowing if there is indeed a Satan. My guess is he does not exist. But I certainly believed he did for the first 50 years of my life. In fact, as much as I like horror movies, I always avoided those with a Satanic theme. I guess I believed in the idea that you could invite Satanic influences into your life if you focused on that kind of stuff.

I have to say that it is very liberating to no longer believe that my choices are influenced by greater powers. I don’t do good things due to the Lord’s influences nor do I do bad things due to Satan’s. It’s just me, every day, trying my best to make reasonable, ethical choices. Nobody to blame when I screw up but me. People believe some pretty fantastic things. Elevated emotion is indeed a powerful force. And I suppose we can allow a perception of evil forces into our lives too. But ultimately, to me these are just mind games we play in order to cope with the ups and downs of life.

Thanks. Although I dislike most horror fiction, I do like discussions on it. Which is why my favorite Stephen King book is ” Danse Macabre”. My complaint with the genre is that over 90% goes for the gross out. Which explains the popularity of the film “The Exorcist” when I was in high school. Everyone talking about a gross looking Linda Blair with her iconic spinning head.

If memory serves, Church leaders warned against seeing it. Cuz you could get possessed somehow??? ( Heard unintentional funny stories in Seminary) So it was years before I saw it.

It was very funny.

At the End of he 80’s. I attended a talk by David Morrell about why he wrote Horror (and yes he kept all the merchandising rights to Rambo). And heard him speak about reading, late into the night, a novel by Stephen King. And kept reading by the hospital bed, as he kept watch over his dying son.

What I find is that for me, we are always possessed. Cast the Demons out and they reach out with wispy barbed tentacles and wrap intertwined with our DNA.

It’s why I’m here.

The demon, Pazzuzu, wins when Fr. Damien opens himself to be possessed by him, then commits suicide. The demon, of course, survives, but Fr. Damien presumably goes to hell for his disbelief in God–not because he disbelieves in the supernatural (on the contrary, he has experienced it!), but because what kind of God would permit this? God is the true demon.

Well, that sure sounds like a Zla-od opinion (or perhaps the opinion of whatever demon is speaking through Zla’od ;-). Karras might go to hell “presumably” to you, but I see no support for that in the text. Compassion for most, if not all, the characters is everywhere present in the novel. I don’t buy that Blatty takes us through 200+ pages of heartfelt storytelling just so he can have a priest give up and be sent to Hell. Simply doesn’t track, and is also quite cynical.

On the contrary, we have the observations of Father Dyer, who performs last rites for Father Karras and witnesses the fallen priest’s final moments. He describes Karras as appearing to be at “peace,” and just before taking his final breath of having a facial expression that seems to include a sense of “triumph.” Peace and triumph being the author’s words, given through Father Dyer. Not descriptors for the mood of a soul about to be dragged into a lake of fire and brimstone. More like the ecstasy of the martyr Stephen in Acts 7 (though that’s speculative on my part). The text is deliberately unclear about Father Karras’s eternal fate, so there is no textual support for your assertion.

Now! My take works if you see Karras’s act not as suicide but as sacrifice. He pulls the demon into himself to free the girl, and then throws himself out the window, literally removing the demon from the house and depriving it of the chance to continue harassing the occupants. All of this hearkens to the Gospel account of Jesus taking the demon(s) out of a possessed man and placing them into a herd of swine which then runs off a cliff. We know Blatty, the author of The Exorcist, had this in mind because he cites it specifically during the exorcism chapter, having Father Merrin read the passage aloud (Luke 8:28-33) as Karras follows along. But, y’know, The Exorcist is a yarn. Read it however you want.

Thanks to each of you for your interesting observations. I appreciate you sharing them!

Thought I would mention The Exorcist is getting a 4k release in a couple days. Both the Theatrical and Directors cut. Not much in way of special features but it does include commentary by William Peter Blatty. Also next month (probably to capitalize on Halloween) coming out is some sort of sequel.

Not knowing much about Catholicism, I can’t really comment on author’s intent in The Exorcist. What my secular eyes sees is slick propaganda that uses superstition to demonize a girl becoming an adult. And a man rejecting rationality and jumping out a window. And this is somehow a virtue. Looks like Darkness wins.

Suzanne, thank you for sharing a very different take than mine. In defense of my take, I feel like the movie goes all in on an authentic possession. That is to say, within the universe of the movie, demons are real and this is an actual minion of Satan possessing Regan. So, strictly speaking, in the context of the movie, Karras is being rational in his approach to casting the demon out. But that’s creative writing nitpicking on my part.

I do feel, for all its bells and whistles, like the novel leaves the door open for this all to have been hysteria, not an actual possession. Which only gives more space for your thesis to be compelling. More importantly, I can only assume that there are more, and more blatant, examples from film and novels where a young girl’s maturation is effectively demonized/commodified/lampooned. Just want to welcome for all my readers what you’re saying about the presence of both veiled and unveiled misogyny in culture and literature. Thanks for commenting!

I get in the context of the film it’s real. But I don’t believe in demons or magic, and have trouble getting past that. But hoy, place it on a spaceship and I’m good to go.

The movie The Exorcist is considered one of the best movies made and Blatty won an academy award for best screenplay. Yet most of the criticism I’ve read is through a feminist lens. And the film (and book) is seen as deeply, deeply misogynistic. There is nothing scarier in a horror film than a girl going through, um,um bodily changes. Especially one with a single mom. Fortunately, a couple of fathers arrive (unlike for poor Carrie) to save her by inflicting abuse. Yeah for Hollywood.

And to move from the fictional world to the actual shooting of the film. Ellen Burstyn permanently injured her back,“I said: ‘He’s pulling me too hard.’ Billy [Friedkin, the film’s director] said: ‘Well, it has to look real.’ I said: ‘I know it has to look real but I’m telling you, I could get hurt.’ So, Billy said: ‘OK, don’t pull her so hard,’ and as I turned away, I felt him signal the guy and he smashed me on the floor. I expected Billy to yell cut. Instead, I saw him touch the cameraman’s arm to move the camera closer and I was screaming at the top of my lungs. Through my screams, I said: ‘Turn the fucking camera off.”

And Linda Blair who had chemical burns from makeup, also fracturing her spine. Nothing like real screams to add authenticity.

Of course the book has no bearing on happenings on set, unless both are sailing in the sea of blah,blah,blah.

I am not seeking to blame literary creations (we have enough problems with book bannings), but view them as indicative of a culture that bleats “Protect Children” and uses that “protection” to harm them.

Jake: Really interesting take. I have seen the movie, but not read the novel. A horror movie from my childhood that made a big impression on me was The Amityville Horror (it was filmed in the town I lived in at the time, based on a “true” story, and my parents took me to see it at age 11 for Family Home Evening, which was a parenting choice I guess). I like the “You Are Good” movie podcast, and they discussed this film. They talked about several horror films from the 70s, of which this was one, that all shared a certain formula: 1) your family’s problems are all due to Satan, and 2) only the Catholic Church can help. Amityville Horror, for those who’ve watched it or read it, conveniently overlooks and downplays the fact that the stepdad is getting more and more emotionally abusive, and the family is in his control. Instead of criticizing patriarchy and the terrible man running the household, it must be Satan.

But then they spent some time talking about exorcism (or maybe this was on the other Sarah Marshall podcast You’re Wrong About, and the weird thing was that objective studies showed that exorcism…wait for it…works. That doesn’t mean it’s necessarily casting out demons, but the ritual (for believers anyway) alters the symptoms of the afflicted. I’d have to go back and re-listen to it because it’s been a while.

Anyway, very interesting thoughts. Thanks for sharing! This sounds like great book club fodder. Have you considered starting a virtual book club? (I’d also recommend some other 70s staples like Stepford Wives, but the book).

Hi Angela. Thanks for mentioning the objective studies. Such an important point. One of the things where the movie stays close to what the novel discusses in more detail, The Exorcist discusses the suggestibility factor. Ironically, the credulity that gets a person into believing they are possessed is the same thing which enables them to be freed via exorcism. In The Exorcist, even Karras advocates for pursuing biological/medical methods above all else. When those fail, psychiatric methods serve as a fall back. Only when those also come up short, is exorcism on the table as a last resort. A more recent film, The Exorcism of Emily Rose, addresses this in a courtroom dialogue where they talk about the ritual providing a psycho-spiritual shock that the victim needs to bring them out of the mental state, regardless of if it’s authentic possession. Fascinating to me

Like you, I remember Amityville Horror being a big deal, but I don’t think I ever watched it. Poltergeist was the one my folks let us try as kids. I guess a guy tearing his own face off is okay as long as Spielberg is producing and Satan isn’t involved, just nondescript ghosts…

Jake C.: (hjss) Your mother drinks coffee in the Telestial Kingdom! 😉 But yeah, I forgot about the last rites. It’s been awhile. There were sequels too, but we don’t talk about those…

Some good movie demons in “Hereditary” and “A Dark Song.” (Goetic / Solomonic, not Catholic.) For novels, I like “Son of the Endless Night” (John Farris) where a fundy exorcist drives a van with a neon cross on it, speaking in “the Unknown Tongue” through a loudspeaker. I mean, demons can’t all be high church Catholic!