Today’s guest post is by Faith. It is the latest in a series of posts focusing on the careers of leaders in the Church. The previous post in the series can be viewed here:

As a reminder, all of us have our own personal issues, it’s not white hats vs. dark hats; it’s all different shades of gray. We want to be tougher on systems than we are on people. However, when a “leader” tells other people how to proceed with life choices and the leader’s past reflects other choices, what are we to think and how are we to act? The facts in this history are controversial and a darker gray, when shown in the light.

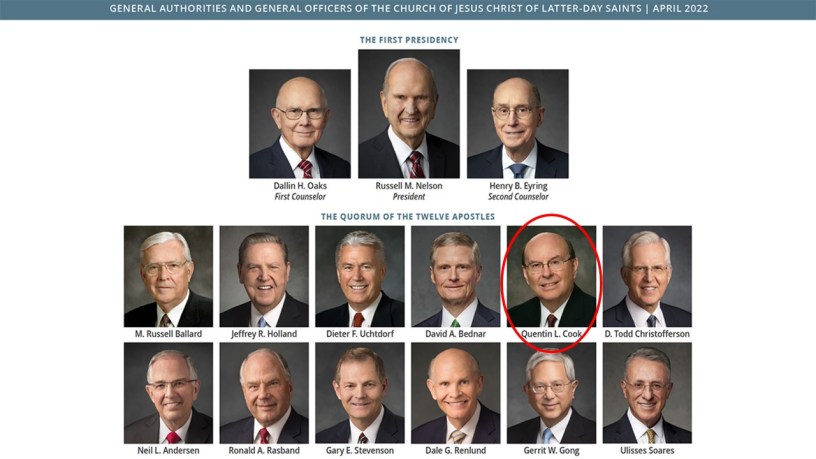

Quentin LaMar Cook

Quentin, following a Q15 preference pattern, was born in Logan, Utah. He served an LDS mission to England. He graduated from Utah State in 1963, then Stanford Law in 1966. He remained in the San Francisco Bay area, working as a corporate attorney for 27 years with Carr, McClellan PC. In 1985, he created California Healthcare Systems (CHS) which managed Marin General Hospital (MGH). Cook was CEO and President of CHS. In that role, he later negotiated the 1995 CHS/Sutter merger. He then became Sutter Vice Chairman. He resigned in 1996 to administer in the LDS Church. For the church, he was called to the 2nd Q70 in 1996, then the 1st Q70 1998, and finally an Q12 apostle in 2007. In a talk, as a Seventy, Cook stated “The word saint in Greek denotes set apart, separate, [and] holy. If we are to be saints in our day, we need to separate ourselves from evil conduct and destructive pursuits that are prevalent in the world. As saints, we also need to avoid the worship of worldly gods, including pleasures, profits, credentials, titles…as we love them more than the poor and the needy. Everyone might have some of the good things of life, but it is the obsession with riches that cankers and destroys. The saint test to ask oneself is, would our associates recognize that we have separated ourselves from worldly evils?”[1] In the Cook household, there was a saying about “Saturday morning cartoons”. It referred to only pursuing worthwhile goals and not spending time on unfruitful pursuits, like watching cartoons.[2] Let us examine Quentin’s path of trying to be a saint and avoiding “Saturday cartoon decisions”.

The deal with Marin County to CHS

California state law requires counties to provide healthcare for their residents. Marin County took on $MM in debt to build and expand its’ hospital during the 1950-1985 period. [3,4,5] As healthcare evolved, MGH was advised by their legal counsel to create a new entity to stay competitive. The Carr law firm was involved, with Cook as the lead attorney. [6] The hospital administrator/CEO, Henry Buhrmann teamed with Cook to create the new lease. CHS, a new entity, was formed with Cook as the leader. In 1985, a 30-year agreement was signed between Marin County and CHS.[5] The new lease was controversial from the start. One example was that patient revenue could be used for anything and not be returned to the county and its’ outstanding debt. Anytime there was more money in the hospital bank account than needed for the 14-day business operation, MGH has the right to “sweep”. This is known as an “excess cash transfer”. In the first two decades, this was less than $3MM/year. After 2006 this was up to $30MM/year.[7] In theory the funds are transferred to other hospitals, within CHS, needing the money. However, some reports showed, some patient revenue even made it to the Cayman Islands on a one-way trip. Siphoned money is patient revenue diverted from patient care. There were accusations that CHS/MGH had diverted funds for corporate gain, while the outstanding Marin County bond debt increased to $1 Billion.[8] In layman’s terms this is known as stealing public assets. The transactions were legal, if they went to other hospital systems, however the books were closed to the public with no transparency. MGH, became a victim of its’ 1985 lease. The covert purpose of the lease was to remove decision making from public oversight and review without a vote of the district residents. In 1995, CHS/MGH merged with Sutter Health.[5]

CHS business results

The 1985 lease did not require quality assurance. The hospitals’ internal statistics reflected the change transitioning to a business model. The ratio of nursing staff (RN, LVN, Aide) for inpatient care placed MGH in the lowest quartile of hospitals. Sutter/MGH reduced in-patient RN staffing by 42% and reduced licensed (Physical Therapists, Pharmacists, Phlebotomists) available by 73.9 %. Use of unlicensed caregivers increased 1000%. A January 1995 JCAHO full survey accreditation visit resulted with MGH in the lowest 5% of hospitals. In March 1997 Sutter/MGH falsely testified before the district board that although MGH is licensed for 235 beds, the corporation had no capacity for more than 140 beds, within 36-hours following a potential disaster. Employee morale was low with physician vs Sutter/MGH management having an “attitude” problem. Professional staff who brought violations to the attention of the district and/or state regulators were harassed, reprimanded, fired, transferred, and sued.[8] Numerous complaints were filed with CA State Department of Health services describing life-threatening care deficiencies to acutely ill Marin patients. Cutbacks at Sutter/MGH raised widespread concern over the adequacy and availability of emergency medical service. By August 1997, Sutter/MGH no longer guaranteed full-time neurological staffing. This would have cost the highly profitable Sutter only $1,000 for MD coverage, every fourth weekend.[8] This is exemplified by the death of Jennifer Childs on September 27, 1997, and the inferior medical care leading to her passing.[9]

Investigations

MGH quality care issues never seemed to end. An 80-page Federal Government investigation reported in the Marin Independent Journal, describing 50 separate patient-endangering deficiencies. [11] Missing documents became common. The pre-contract 1984/1985 board agenda packages were missing entirely, no pre- 1986 taped records were found, and the 1995 tapes are missing for meetings discussing the merger. Financial records were in such disarray that the board is unable to determine if several hundred thousand dollars due to the district under the lease were collected. [9] Nevertheless, everything went according to hospital management plans until November 1996. Voters recalled two elected board members and voted in two consumer advocates for the Marin Health Care District. Suddenly, the majority of the board consisted of watchdogs. Lapdogs were now in the minority. Immediately, the management of MGH/Sutter began a campaign for mediation between the elected board and the hospital. Then a lawsuit ensued.

By way of contrast, El Camino Healthcare District, in Mountain View CA, lost $31 MM from 1994 to 1996 under a similar lease with CHS. The El Camino district successfully sued to break their lease on the grounds that a conflict of interest existed in its’ formation. This hospital lease was also created by Quentin Cook. When the county regained control, El Camino earned $17 million in the first six months of 1997 as an independent district hospital and with no cash sweeping involved. Then El Camino Hospital profits were redirected to increased staffing, purchasing new equipment, and improved healthcare within the district. The elected directors got the hospital back from CHS. It now operates profitably, openly, and honestly. [9]

Just as El Camino did, Marin County initiated a lawsuit to regain control of their hospital. The district alleged a conflict of interest, and the lease violated their public mission. The lawsuit heard in Sacramento Superior Court was that Buhrmann and Cook broke California law. Cook was a public employee when starting CHS. It is a violation of the California Government Code, Section 1090, for a public employee to make contracts that benefit himself. Later, both Buhrmann and Cook left public employment to join the private MGH Corp. [9] They made money in the transition. The lease in itself was legitimate, however with Cook violating section 1090, could result in making the original lease void. [10] However, the judges covered Cook. The Sacramento judge ruled that the four years statute of limitations had been exceeded. She made no ruling on the merits of the case. The California Supreme court concurred. By case law, the judge could have considered the case because there is traditionally no time limit when public property is involved. The court solely based their decision on the statute of limitations expiring.[9,10] In 2010, the Marin Hospital returned to under control of Marin Health care district, 5 years early with the lawsuit negotiation, after 25 years of controversy.[11]

Cook Legacy

Cook’s work in privatizing hospitals in California involved a lot of dissentions. As an attorney he represented the Marin County Hospital District, drafted the lease, and was the original CEO of CHS. As an attorney representing other public hospital districts, he negotiated deals favorable to the nonprofit healthcare corporations. Two weeks before the Marin lease was finalized, he resigned as the hospital district’s attorney. Shortly after, he went to work for California Healthcare Systems, that he created.[12] I am not implying, Cook ever took any of the funds, but he did write the contracts that set the groundwork for it to happen by future management and he was remunerated with a large salary for his efforts. Cook left management before some of the examples provided. However, he was the founder and pioneer of the system. Cook did break the law, under section 1090, by profiting in his transition from CHS to Sutter Health roles. He created the leases, at a minimum, for Marin and El Camino hospitals and possibly another 16 hospital systems, for which the records are not available. Critics claimed the deals quietly gave public revenues to private interests. The hospitals became part of CHS, which later joined Sutter Health. Cook became the second-ranking executive in the new combined corporation. [12] His 1995 CEO salary was $311,479, just from CHS alone.[9] We have no additional information about his other salaries, bonuses, and profits from his decision making. He profited while employees and patients suffered under the business arrangement. Commenting on the contract Gary Giacomini, then a county supervisor, called it “the biggest theft of public property in Marin’s history.”[9] Critics question if Cook should have faced disbarment with enriching himself, at the client expense. Additional pertinent press articles to this are included below, although many have been erased with time. [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]

Similar to Kevin Pearson’s relationship with Optum/United Health Care, Quentin Cook created a system, profited, and then left for LDS pastorship.

Legacy in 2020s

This 60-minute TV segment shows that state of Northern California health care and the effects of Sutter health. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/california-sutter-health-hospital-chain-high-prices-lawsuit-60-minutes-2020-12-13/

Reflection

Are these the actions of a Christian Saint that avoids evil conduct and worldly gods?

Did Cook separate himself from “worldly evils” and uplift the poor and the sick or is there a pattern of the obsession with riches?

Does this account represent a worthwhile life goal, or did it have the value of a Saturday morning cartoon in the end?

Was it convenient that Cook was called as a General Authority in 1996, requiring him to resign just as the public outcry and government investigations were increasing?

Did Quentin Cook leave a legacy for good or a legacy of victims with problems in Northern California?

Are there similarities to CHS/Sutter to the way the LDS church handles its’ operations?

References

- https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2003/10/are-you-a-saint?lang=eng

- https://www.thechurchnews.com/2021/12/7/23218154/elder-cook-byu-pathway-devotional-worthwhile-goals

- https://caph.org/about/members/public-health-care-systems/

- https://medium.com/anne-t-kent-california-room-community-newsletter/marins-county-hospitals-cda62ef3dbe2

- https://www.marinhealthcare.org/about-us/our-history

- https://www.carr-mcclellan.com/our-firm/firm-history/

- https://www.northbaybusinessjournal.com/article/industry-news/marin-healthcare-district-sues-sutter-over-120-million-in-transfers/

- http://www.smartvoter.org/2000/11/07/ca/mrn/vote/severinghaus_j/paper2.html

- https://jweekly.com/1997/10/10/marin-crash-victim-19-lived-precepts-of-judaism/

- https://caselaw.findlaw.com/court/ca-court-of-appeal/1464984.html

- https://www.bondbuyer.com/news/marin-county-district-wins-back-hospital

- https://www.metroactive.com/papers/sonoma/01.11.96/frontlines-9602.html

- https://www.marinij.com/2010/08/26/attorney-sutter-engaged-in-120-million-rip-off-of-marin-general-hospital/

- https://www.marincounty.org/-/media/files/departments/gj/reports-responses/2003/healthcareoptionsfinalreport.pdf

- https://www.northbaybusinessjournal.com/article/industry-news/did-sutter-single-out-marin-to-take-funds/

- https://www.bizjournals.com/sanfrancisco/blog/2013/01/marin-general-hospital-wins.html

- https://www.marincounty.org/-/media/files/departments/gj/reports-responses/2001/hhs1_final_report_061202.pdf

- https://publicpay.ca.gov/Reports/SpecialDistricts/SpecialDistrict.aspx?entityid=1552&year=2021

- https://publicpay.ca.gov/Reports/SpecialDistricts/SpecialDistrict.aspx?entityid=1552&year=2010

I commend you not only for your in depth research, but also the time you’re devoting to this series. It is not a small thing.

Considering that the Church hides the majority of their finances, and misrepresents some of the stats they do share, it would seem that Elder Cook fits right in at the COB. And no, these actions are not those of a Christian Saint, but rather a top tier member of a multi-billion dollar business.

You can get anything you want in this world with money.

Being raised in the church as a Republican and seeing money seem to become the central theme of both, it’s hard to trust anyone anymore.

Your research and summary appear excellent, but it’s hard to assess Cook without hearing his side of the story. I for one don’t really care about his corporate and legal past, although any evidence of hypocracy from a Q12 member is troublesome. What bothers me is what he says out in the open as a member of the Q12. Among the highlights (lowlights) that I can recall off the top of my head:

1. The Church was persecuted because it was against slavery

2. Church membership was never expected to be large in number, only strong in its faith

3. Various implications from him that he has seen Christ

Ask yourself a simple question: Do you trust QL Cook?

And there was I thinking that they ask potential GAs whether there’s anything in their past that might cause the church embarrassment.

What would it take to embarrass the Q15? Clearly financial shenanigans doesn’t appear to be it..

It’s all so disheartening.

Thank you for bringing this to my attention in detail Faith. I’d seen / heard it mentioned in passing in other forums.

The last words I heard in a general conference were of Cook in October 2105 declaring that “Christianity is under attack” (apparently a phrase he has said multiple times elsewhere). I immediately turned it off and haven’t listened again.

I would say that my expectations of honesty has way less to do with whether I or Elder Cook ever did something less than honest in our lives. I don’t think it’s reasonable to expect

anyone of us has never acted in self-interest, willing to be dishonest for our gain, however, the problem is the Q15 put on a mask of perfection, acting as though they have never acted below the belt. I think honesty, in God’s eyes, has way more to do with being honest about our lives, willing to share the good, the bad and the ugly, so we can all learn together and acknowledge the harm we have done in the world. Our culture favors looking righteous over honesty, and we get what we pay for.

Unfortunately I am unsurprised by the financial shenanigans, but dissing Saturday morning cartoons (Bugs Bunny and the Road Runner) is beyond the pale.

Thanks Faith for another eye opening look into the backgrounds of the Q15. Are we starting to see a pattern yet in the type of men who are being called to the highest levels of leadership in the church?

I have an older relative who worked as a surgical nurse with Nelson back in the day, and the stories she’s told me about his behavior in and out of the OR do not reflect well upon him. DHO ran BYU as his own personal fiefdom and went overboard trying to root out LGBTQ+ students, persecuting them, having them subjected to what basically amounts to torture under the guise of conversion therapy and which then drove some of those poor souls to attempt or actually succeed in taking their own lives out of despair. Ballard was known for his poor business management abilities and dodgy business dealings. Cook and Stevenson too. That’s 1/3 of the Q15, and those are just the stories we actually know about! Is it any wonder that the SEC has had to fine the church (EPA specifically) for its use of “creative” accounting practices? Throw in rampant nepotism and a church version of the “Good Old Boys Network” and it begins to become very problematic.

Unfortunately, if you are a serious student of church history this is a continuing pattern of very flawed men who are not the kind of examples of Christlike attitudes and behavior that ought to be leading a church. And yet, these same men constantly insist that we give them special treatment and attention, obey them implicitly and let them do everyone’s thinking for them. Can we say cognitive dissonance anyone?

Thank you again, Faith.

I remember Elder Cook’s GC address from not too long ago in which he directly stated that the early Saints’ persecution was a result of them opposing slavery. I was livid when heard it, because it was not merely an obfuscation of the facts of history, or a gentle massaging of the truth (like the Gospel Topics essays do), but an outright lie, told so boldly in front of a global audience by someone who should know better. Then the following conference, he talked about the Mormon pioneers who settled the Utah territory and how kind and compassionate they were to the Native peoples who were already living there, which even a middle-school reading of Utah history shows is patently false. Two consecutive public lies about the Church’s history that both attempt to frame the institution in a less racist light is not a coincidence, it is a pattern. And in light of his past corporate attorney hospital shenanigans, it tracks with the profile of an attack-dog lawyer who is willing to do anything (and I mean *anything*, including but not limited to crossing ethical boundaries) to protect his wealthy client, whoever that may be, as long as the experience is also profitable for him.

That’s to say nothing of his key role in dismantling pubic health care institutions, while building up the for-profit healthcare system that literally enslaves millions of Americans in debt bondage and profits off of human suffering. He is not solely to blame, but he was actively part of the problem, and had numerous opportunities to make better, more Christlike choices.

Great series, keep it up!

Learning about Quentin Cook’s legal shenanigans at a freakin’ hospital–where legit human lives are at stake!–is especially disheartening, because he is how I first learned that the whole “eye of the needle referred to a back gate in Jerusalem” reading of Matt. 19:24 is total nonsense. He had published an article for the Ensign during my mission when he was still in the Q70, wherein he matter-of-factly noted how there was no such gate, that Christ was using hyperbole to drive home an important point.

The details of the rest of the article are hazy now; but as a then-recent seminary-grad who had been repeatedly told throughout high school that Christ only insisted that the wealthy be humble–that he did not actually intend for them to sell all that they have and give to the poor–it was a watershed moment for me to realize that Christ may have in fact literally meant what he said.

I’ve never found a Cook talk to be all that memorable or engaging, but that old Ensign article, combined with his ecumenical outreach, had caused me to just sorta assume that his heart was in the right place. But then, he would hardly be the first person to preach all the right things while still failing to practice it.

Jack Hughes,

I think your interpretation of Elder Cook’s statements is too broad and general. In his talk he carefully contextualizes those statements (you speak of) in order to keep them narrow and specifically applicable to the theme he’s addressing. For example, when he mentions the difficulties in Missouri he says that it was “a time of tension on several fronts.” And then he goes on to mention two areas of discord between the saints and the Missourians. So he’s not saying that the saints were driven out of Missouri solely because of their opposition to slavery.

Also, when he speaks of how Native Americans were treated by the saints he’s telling a story of a specific group — one person really — in Fillmore Utah who treated the Native Americans with dignity and respect. And then he immediately qualifies that story with this following statement: “As leaders, we are not under the illusion that in the past all relationships were perfect, all conduct was Christlike, or all decisions were just.”

Faith – thanks for all the time and effort you put into researching these articles. It’s discouraging to hear of people who prioritize profits over peoples’ health. There is so much room to do good in the realm of healthcare. But it takes so much effort to corral the greed.

It would have been better if he’d just watched Saturday morning cartoons! Better to waste time frivolously than to work to actively make life worse for sick people.

I think having only wealthy lawyers and business men as the leaders of the church is problematic. It seems that they don’t have a clear understanding of those of us working and living in humility, poverty and various difficult situations. Representation of people in many different situations matters when it comes to leadership. Those of us with different situations could really help the church succeed, if we were invited and listened to, and accommodated. Unfortunately it’s just much more comfortable to call someone like yourself that you admire because of the very fact they are like ourselves. We become more and more isolated with a more narrow perspective as we spend more and more of our time on leadership with people like ourselves focusing more and more on a narrow view of the world. Eventually, as they spend more and more years in this way, hiding away from the world associating with others like themselves and studying mostly the same religious texts, I fear our leaders can become somewhat blind to the very situations they are supposed to understand and offer leadership for.

Our health care systems are profit focused and have become more and more beaurucratic and monopolistic. They hurt families like mine with multiple members that are chronically ill. I imagine Cook chooses not to focus on or empathize with people who are chronically ill. He must not truly understand the effects of his actions.

I however, do understand the effects of Cook’s for profit actions more than I want to understand. I will never look at him in the same way again. I can’t help but hope that God will bless him to truly understand the effects of his actions, by suffering chronic illnesses of himself and family members he cares for before his death. You may think I am being vengeful and uncharitable to wish this for him. However, a life of comfort does not truly bring spiritual growth. I hope he has the experiences he needs to grow before he dies and faces God’s judgement for his actions as a leader both in and outside the church.

Thank you for the carefully sourced and documented article Faith.

Picking leaders is difficult. You need managers to handle the corporation, you need lawyers to advise on legal matters. But the corp Church needs to be more Christlike and the institution needs to be less litigious, much less. Cook doesn’t seem qualified to handle either area, plus there is the question of his ethics.

The Q15 could use a scientist and a social scientist. It also needs blue color workers. Most GAs seem weak on history and need to consult historians. They are weak on science. How about having an ethicist on call?

Elder Cook regularly shares his *sure* witness of the gospel. And I think his usage of the word “sure” echoes the kind of knowledge that Peter speaks of in 2 Peter chapter 1.

When Institutional Policy Harms the Congregation

As time passes, and we learn more about the harm caused by the pharmaceutical fraud that drowned the world economy, and the countless lies propagated by world leadership made to promote the most corrupt profiteering scheme ever witnessed by humanity—perhaps we will recognize how our Elect have been deceived: “For by thy [pharmakeia] were all the nations deceived…” (The Revelation 18:23).

The LDS colleges have harmed student health and birthrates of the Restored Church by mandating mRNA genetic experimental virus exposure cloaked as life-saving medicine.

BYU Hawaii still has the mandate in place to guard admissions—a scientifically backward policy which harms students, a policy that cannot be supported by data. If we learn that the institution has profited from owning stock in the pharmaceutical corporations that have deceived the world, our hands are unclean. If we invest the sacred tithe in evil, profiteering corporations of “the world,” our offering is unacceptable, and mocks the Restored Church.

Here is a short (a little over one minute) audio clip of Quentin Cook seemingly claiming to have seen and spoken with Christ: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2xRO4nPbrxk. Here is a quote from Church coverage of this talk (https://news-ph.churchofjesuschrist.org/article/elder-cook-reminds-youth-and-ysas-of-their-divine-role): “Elder Cook concluded his message by sharing his testimony of the Savior. A hush came over the congregation as he bore his witness, ‘I know the Savior’s voice. I know the Savior’s face. Jesus Christ lives.'” It is worth listening to the whole audio clip since Cook spends a bunch of time stating how it’s important not to share sacred experiences with others before seemingly going ahead and violating his own advice and claiming to have seen and spoken with Christ.

Another, slightly less egregious, example of Cook doing a similar thing can be found here: https://www.ldsliving.com/stunning-video-footage-accompanies-elder-quentin-l-cooks-sure-witness-of-jesus-christ/s/94182. In this one he again prefaces his comments by stating that he can’t share his sacred experiences, but then immediately claims that due to these un-shareable sacred experiences that he “can testify with all certainty as a sure witness of the divinity of Jesus Christ.”

Note that according to Dallin Oaks, Cook has probably not seen Christ. At a 2016 devotional, Oaks stated that he had never had a heavenly visitation like Alma the Younger had, nor had any member of the FP or Q12 (that he was aware of), “I’ve never had an experience like that and I don’t know anyone among the 1st Presidency or Quorum of the 12 who’ve had that kind of experience. Yet everyone of us knows of a certainty the things that Alma knew. But it’s just that unless the Lord chooses to do it another way, as he sometimes does; for millions and millions of His children the testimony settles upon us gradually. Like so much dust on the windowsill or so much dew on the grass. One day you didn’t have it and another day you did and you don’t know which day it happened. That’s the way I got my testimony. And then I knew it was true when it continued to grow.” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GrMJ2YZD62M, start at about 1:25 of the video).

It appears to me that Cook intentionally prefaced his remarks with the warnings against sharing personal experiences so that he could use intentionally vague language while referring to his experience(s) with Christ. “I know the Savior’s voice. I know the Savior’s face.” and “I can testify will all certainty as a sure witness” do not necessarily mean that he’s had a face-to-face physical conversation with Christ, yet a huge percentage of Church members who heard Cook make these statements (and who listen to the clips now) are going to assume that Cook is indeed claiming to have had a face-to-face physical conversation with Christ. This use of language from Cook seems extremely deceptive and manipulative. As Oaks says, Cook has almost certainly never physically seen or spoken face-to-face with Christ. If Cook didn’t intend his remarks to be deceptive, then he should clarify that he hasn’t seen Christ. If they were intended to be deceptive, then he should first apologize and then clarify that he hasn’t seem Christ. He will, of course, do neither of these things.

If Cook would like to share his testimony of Christ in the future, he can simply say something like, “I’ve had sacred experiences that I don’t feel I can share. Let me be clear, the FP, myself, and the rest of the Q12 have never seen Christ, and we are not likely to ever see Him in our lifetimes. However, the sacred experiences that I’ve had, which are similar to the spiritual experiences that many of you have had, allow me to bear this testimony to you…” If Cook just wants to start with his testimony without first mentioning his “sacred experiences” that he can’t share, then this whole preamble is unnecessary, but if he is going to insist on leading his testimony by teasing listeners with a mention of all his un-shareable sacred experiences, then he should at least clarify at some level the nature of those special experiences–in particular, they do not include a face-to-face personal conversation and that they are basically the same types of spiritual experiences that many Church members have had. Without such clarification, many Church members are going to assume that Cook has seen Christ. Unfortunately, that’s exactly what I think Cook hopes they believe, and if so, that’s extremely deceptive.

Wow @faith, tremendous reporting! I was tangentially involved in some litigation involving Sutter Health at the very beginning of my legal career. I had never bothered to look into what Cook had to do with Sutter, but was generally aware of issues around the privatization of hospitals in CA so had wondered if there was anything to it. Indeed there is.

I agree that we need fewer lawyers and businessmen in the Q12. Also, as a lawyer, I can confidently and with integrity say that I’ve never done anything in my capacity as a lawyer that I would be uncomfortable with seeing the light of day. I truly don’t think I’ve represented an interest that hurt people or made life worse for people. And there are many, many other lawyers who could say the same. So we really are managing to find some rotten apples to lead.

Totally agree about the shadiness of the implication that he’s literally seen Jesus.

I’ve thought about what a write-up about me might look like, and while I haven’t done anything I considered shady, I have had the unfortunate role of doing a lot of layoffs which were definitely an impact to people’s lives. It didn’t benefit me personally, however, and as an executive, I was paid less than my colleagues (as my boss frequently told me and worked to rectify with off-cycle raises). At one point, after I did some requisite layoffs and closed a remote location (offering WFH positions to the majority of the employees as an alternative), a local pastor published an article about me, calling me heartless and shameless for ruining this small town with my corporate greed, which is definitely a mischaracterization of what happened. Sometimes businesses have to lay people off or close down a remote facility because maintaining it would be a bad business decision. It’s not easy, but I’ve had to do it probably half a dozen times (more layoffs than that, but actually shutting down a site is what I mean). So, it’s possible that a few people out there still think I’m a monster.

mountainclimber479,

Elder Oaks was talking about the process of getting a testimony–not the question of whether or not anyone has seen the Lord. To the best of his knowledge none of the apostles have received a witness of the truth in one blinding experience as did Paul or Alma. They learned it quietly and incrementally just like the vast majority of us do. Even so, that’s not to say that they haven’t had experiences that are too sacred to share. They have–and so have many of the rank and file members of the church.

Jack,

Just like Bill Clinton tried to debate the meaning of the word “is” in response to his sexual misconduct, it seems to me like you are debating the meaning of the word “never” because you feel the need to live in a world where the Q15 has literal visitations from Jesus on a regular basis. Yes, Oaks’ statement was in response to a question on how to obtain a testimony, but Oaks’ statement is still pretty darn broad and clear. When he says “never”, I take him to really mean “never”–which means his entire life. Here’s the quote again, “I’ve *never* had an experience like that and I don’t know anyone among the 1st Presidency or Quorum of the 12 who’ve had that kind of experience.” I think if Oaks had seen Jesus after obtaining his testimony, he would say something more like, “In my younger years while my testimony was still forming, I never had an experience like that, and I don’t know anyone amount the 1st Presidency or Quorum of the 12 who had that kind of experience while gaining their testimonies, either.”

There are a lot of things Oaks has said and done over the years that I vehemently disagree with. However, in this case, I applaud Oaks’ honesty and clarity. So many Mormons truly believe that the Q15 literally converse with Jesus on a regular basis and because of that they accept anything said by the Q15 from the pulpit as the word of God. I thank Oaks for being honest and setting the record straight. I would only ask that he, and all of the Q15, publicly state that they’ve never literally seen Jesus at the next General Conference. I nominate Quentin Cook to be the first to stand up and tell the truth about his literal, physical conversations with deity since he’s made so many of these misleading statements in the past. I’d also love to see Cook, in the same GC talk, stand before Church membership to give his side of the story in the hospital privatization mess that he was involved in, and to apologize if he recognizes he was at fault.

The recent POX debacle is a perfect example of how I believe the Q15 does typically receive “revelation”. They study things out, they discuss/debate, and they pray. Eventually, the answer comes to them like “so much dust on a windowsill or so much dew on the grass”. If you read Nelson’s description of the POX and its revocation, you will see that this is exactly how he says things happened with the POX decisions. Each member of the Q15–according to Nelson–felt they’d received revelation to enact the POX in 2015, and then again to revoke it in 2019. The Q15, even when acting in unison, got it wrong with the POX, just as they’ve gotten things wrong with other “revelations” in the past. It would sure be nice if Jesus would literally converse with the Q15 more frequently to avoid the pain and suffering caused by false revelations such as the POX, but it appears that He is willing to allow His Church and its leaders a lot of leeway to make mistakes–if only we, and especially the Q15, could learn a little from these mistakes.

Finally, in my previous comment, I was not raising an issue of whether or not the Q15 or rank and file members have had sacred experiences that they don’t feel comfortable sharing. That’s fine. However, I do find it very disingenuous for people like Quentin Cook to tease or lead on Church membership with such claims of fantastical, mind-blowing, supernatural experiences, especially when using such claims to justify other statements or teachings they are making. “Oh, gosh, I sure would like to share with you some of these super sacred experiences I’ve had, well, maybe I will…No, darn it, I guess the blasted scriptures say I just can’t share them with you, but *wink, wink* I will just say, ‘I know the Savior’s voice. I know the Savior’s face.’ *wink, wink*” If you’ve had a sacred experience, and are going to share it, then actually share the experience. If you’re not going to share it, then just make your statement/bare your testimony without manipulating your audience with hints of experiences “too sacred to share”.

The “too sacred to share” is absolute BS.

The early apostles shared their witness of the resurrected Jesus.

Early church members, starting with Joseph Smith, recounted their experiences with visions and healings.

A witness that refuses to describe what he or she witnessed is useless to everybody else. If someone had really seen Jesus and wanted to convince others that Jesus is real, they would describe what they say.

The “we don’t share” is aimed at two goals:

(1) prevent ordinary members without the right rank from gaining a following by sharing such experiences (a la Denver Snuffer);

(2) cover for the fact that unlike Jesus’s apostles and other early Christians and early Latter-day Saints claim to have done, our modern day apostles have never had that kind of experience. Ever.

Those who are mature in the faith do not share all that they know. And the scriptures provide many examples of instances when the Lord commands his servants not to share everything the he reveals to them. It is commonly understood that towards the end of his life Joseph Smith become a rather lonely individual because of everything he knew and could not share. And such has been the case for many of the saints in every age. The were strangers in a strange land not only because of the way the demands of living the gospel separated them from the wicked. But also because of what they knew — “the vision of all” — that they could not reveal to others except as they were constrained by the spirit.

These things are real, my friends. There is an upper world–and because we (fallen creatures) are not capable of receiving a complete knowledge of heavenly things all at once it only stands to reason that there must be knowledge had by some that is too sacred to share.

I met people on my mission in Brazil who told me they had seen Jesus. I don’t doubt they had that experience. I also don’t think seeing Jesus necessarily equates to a corporeal Jesus actually visiting you. Im guessing most of us here feel that way about Marian apparitions. We believe people experience them but we don’t believe the historical Mary is actually involved.

I think Elder Cook’s statement could be easily explained by the following scenario: He had a dream in which he saw Jesus and, because he is an apostle, he thinks this means the Jesus he saw in his dream is the real Jesus. That would explain such a statement as “I know his face.”

I’m purely speculating here but I imagine the Q15 do have visions of deity occasionally. Men of their age, not always of sound mind, prone to believe their every early-morning thought is revelation—statistically, it’s bound to happen once in a while. I also imagine they strictly police each other on not talking about these to the membership so they don’t undermine each other or church doctrine. Early church leaders had conflicting visions and competing seer stones and such. I’m honestly glad they don’t bring that kind of chaos to the pulpit today. But also, I wish they would stop insisting they have any special knowledge or authority over the members, especially in light of closet skeletons like those mentioned in the OP. Yikes.

The mental gymnastics involved in insisting that the fact that people don’t share experiences of visions actually proves they have those experiences is pretty spectacular.

@kirkstall, on the one hand, I get what you mean about people not sharing every passing whim over the pulpit. Except that they do. Andersen on abortion. Oaks on gay marriage. Nelson on the evils of using the word Mormon. These are their passing whims, personal preferences and pet peeves, that they choose to inflict on everyone else as if it’s gospel truth. And if they are supposedly apostles just like Jesus’s were, then I don’t think it’s unreasonable to expect them to have had some kind of experience like that AND bear witness of it. And then people can judge whether it seems credible or not. Perhaps if that kind of conflict were actually on display people would realize that these are in fact personal beliefs, preferences, and experiences from men who aren’t really any different than anybody else.

The comments are more fun if you read “Jack” as Jack Nicholson essentially telling us in his comments that “we can’t handle the truth.” =)

If someone shared something with me and asked me not to share, then alluding to it without actually sharing it is really inappropriate. So there’s that.

I appreciate learning a side of these men that you won’t get in the teachings of the living prophets class taught at BYU (which I took 20 years ago). The worlds of high/low finance are really a fraught environment but I hope I am doing better.

I was reminded of another moment of honesty and clarity from Hinckley’s interview with David Ransom on the Australian Broadcasting Company’s show “Compass” in 1997:

DR: As the world leader of the the Church, how are you in touch with God? Can you explain that for me?

Gordon B. Hinckley: I pray. I pray to Him. Night and morning. I speak with Him. I think He hears my prayers. As He hears the prayers of others. I think He answers them.

DR: But more than that, because you’re leader of the Church. Do you have a special connection?

Gordon B. Hinckley: I have a special relationship in terms of the Church as an institution. Yes.

DR: And you receive–

Gordon B. Hinckley: For the entire Church.

DR: You receive?

Gordon B. Hinckley: Now we don’t need a lot of continuing revelation. We have a great, basic reservoir of revelation. But if a problem arises, as it does occasionally, a vexatious thing with which we have to deal, we go to the Lord in prayer. We discuss it as a First Presidency and as a Council of the Twelve Apostles. We pray about it and then comes the whisperings of a still small voice. And we know the direction we should take and we proceed accordingly.

DR: And this is a revelation?

Gordon B. Hinckley: This is a revelation.

DR: How often have you received such revelations?

Gordon B. Hinckley: Oh, I don’t know. I feel satisfied that in some circumstances we’ve had such revelation. It’s a very sacred thing that we don’t like to talk about a lot. A very sacred thing.

DR: But it’s a special experience?

Gordon B. Hinckley: I think it’s a real thing. It’s a very real thing. And a special experience.

According to Hinckley, he and the rest of the Q15’s spiritual experiences are similar to what the rank and file members generally describe. There is no difference. The Q15’s experience with deity is identical that of the general membership of the Church and has been for a very long time. Unfortunately, such a mechanism for receiving receiving revelation is apparently so subtle that even the Q15 when acting in unison can misinterpret it (again, the PoX debacle is just one of many examples of this). In fact, this mode of revelation is so fraught that it is apparently quite easy for the entire body of the Q15’s personal biases to be mistaken as revelation as evidenced by the stream of revelations related to gender, sexuality, and family that the Q15 has forced on the Church over the last 50 years, many of which the Q15 has either stopped talking about or explicitly reversed itself on.

I feel like Cook has, on multiple occasions, used deceptive language–“too sacred to share, but let me hint so blatantly that it’s almost like I am sharing”–to give the impression to rank and file members that he has had experiences more special than that which Hinckley and Oaks describe as having. I highly doubt that his experiences are any more sacred or special than those of Oaks, Hinckley, or just regular Church members.

Thank you for this detailed post…it’s important that the saints know this history.

One doesn’t know the pain of corporate healthcare greed until you lose a friend or family member due to cost/access issues. Whether to an emergency room turn-away or cancer or heart disease detected too late because basic care wasn’t affordable, the pain is the same. One of Cook’s early conference talks was about adversity, “Hope ya know, we had a hard time” which was a “stiff upper lip” type pep talk about adversity to the rank and file. Knowing then of his privileged background and the harm that others had received as a result of the profiteering of healthcare at specifically his hands, the talk made my blood boil. After revoking our life-saving access to healthcare, how dare he tell us from his comfy corporate chair and on church-paid health insurance to have a stiff upper lip. I wrote an essay about it on my blog years ago. I still bristle thinking about it.

That being said, I often struggle with the apostle Matthew- the tax collector in the same way. R. Azlan’s “Zealot” delves into the Roman strategy of setting carefully calculated tax rates to ensure eventual default of rural land, thereby flipping Judean subsistence farmers into lifelong Roman indentured servants on what used to be their own land. The Roman army- tromping over the expanding empire needed food- and this way- the Roman state controlled it. Jews who “sold out” sided with Rome for middle class security and enforced these crippling policies on their kinsmen and women and against the Jewish belief that the land had been divinely appointed for the Jews- the Chosen people. If I were a poor Galilean farmer who lost my family land (also God’s land) for Roman conquest at Matthew’s hand, I’d loathe him. I’d probably loathe him more than the Romans, as he was betraying his own. I often wonder how the Apostle Simon the Zealot got along with Matthew. Simon would have been a guerrilla rebel engaged in the ongoing disruptive and sometimes violent uprisings against not only Rome, but Roman sympathizers like Matthew.

We tend to think of Matthew the tax collector as a modern day IRS man (beholden to the people), a dutiful clerk who played an important if unpopular role. But in the context of occupied Judea and ongoing civil war, he had truly sold out his religion and his poorer brothers and sisters to the occupiers for a middle class existence. He was working for the enemy-, the rich and powerful oppressors who had revoked Judean autonomy and liberty.

I never really understood that about Matthew- I had simply been inspired by the gospel attributed (even second hand) to him. That creates cognitive dissonance for me, in the same way that some of ETB’s rhetoric used to resonate with me and now I find that a lot of it disgusts me. Until recently, I was never exposed to his racism or Bircherism.

As I grapple with ETB, Matthew, Cook, Paul (as brilliant as he was), or current leaders at a local and even GA level who engage in the absolutely ridiculous lies of Qanon and a certain political alignment I won’t threadjack us with, I wonder how anyone with the H.G. could follow ungodly ideologies or practices without a single bell going off. I wonder it about myself. How flawed can a leader be before they can no longer be used by God? I wonder how people perceive the Light of Christ and Gift of the H.G. if we as the body of Christ are so divided in its message when it comes to issues of eternal consequence and temporal urgency.

I don’t have the answers, but I just wanted to point out that the ethical q’s you raised about Cook are not new and existed among Jesus’ own apostles. I don’t think the answer is black and white, it seems much more complex. All our rhetoric about “truth” and “truth seeking” floats at such a theoretical level that it never grapples with this ghastly real problem. I’m not just talking about the “human fingerprints” but of serious flaws in identifying and harkening to the light and the abysmal and inexcusable way some leaders treat the poor. I don’t understand how Jesus, who laid down his life standing up against systems of oppression, allows it to happen in his church. And yet, he called Matthew.

My daughter, who is currently serving a mission, shared an email from a friend who is currently in the MTC. The email was long, but the part of interest here is, “[MTC branch president] told us that President Oaks once told him that he has seen Christ’s face, and heard His voice. So that blew our minds. And just adds to how real and important this work is.” It appears that either the missionary misquoted the branch president, or the branch president attributed the quote to the wrong apostle because I’m pretty sure that the branch president is actually quoting Quentin Cook here. See my comments above for more detail, but I’ll repeat one Cook’s quotes here, “I know the Savior’s voice. I know the Savior’s face. Jesus Christ lives.”

Cook has almost certainly not physically seen Jesus’ face or literally heard His voice, yet now we have multiple 18-year-old young men believing that he has. And the cycle of the worship of the Q15 starts all over again with these 18-year-olds because of Cook’s weasel-like abuse of the English language. He chose his words ever so carefully enough to make almost everyone that hears it believe that he has seen and heard Christ while he can still claim later on that he was speaking figuratively. I feel like this is real problem. Quentin Cook should clarify his remarks and tell the truth.

The recent news of Sutter 90 million dollar fine for destruction of evidence and fraudulent billing codes and then an additional 13 million for fraudulent outside lab testing has brought the name on tax documents to the attention of many, JONATHAN ZACHRESON an LDS family soy boy who is the SUTTER HEALTH manager – audit and reporting. Jonathan was recently supported by the PLACER COUNTY GOP and MOMS FOR LIBERTY. Jonathan’s cousin Daniel Zachreson works for EPI GLOBAL- LDS SEDGWICK FAMILY owned company! Jonathan Zachreson and Sutter are working with Newsom and Biden Admin as the elite group of fraudulent billionaires club. These evil people have no soul and are a threat to the American people.

Elder Cook is one of the most humble and kind person I know, along with his wife Mary. We lived in the Bay Area and a family friend. He is misrepresented in this blog. Read his actual words or listen to his talks, and if you have the privilege, meet and talk to him.