TL:DR – Some church critics claim Joseph Smith got the names “Moroni” and “Cumorah” from tales of Captain William Kidd’s exploits on the Comoro Islands in the Indian Ocean. Turns out, Captain Kidd never set foot on Grande Comore island, the location of the current city Moroni, and he wasn’t even a pirate till months after he left the Comoro Islands. The name Comoro (or derivatives) rarely occurs in pirate lore, though the individual names of three islands in the Comoros (Johanna, Mohilla, Mayotta) often do. The name Moroni never appears in pirate lore, and is absent from all pre-1830 maps and literature, except for a mysterious village named Meroni/Merone on mid-1700s maps of the island Johanna. In order to use that village for source material, Joseph Smith would’ve had to view the name Meroni/Merone on one of the few detailed maps of Johanna island, which is unlikely.

With pirates at the box office, it seems appropriate to talk about how pirate legends may (or may not) have influenced the creation of the Book of Mormon. Ever heard the one about Joseph Smith getting the names Moroni and Cumorah from the scandalous piratical tales of Captain William (a.k.a. Robert) Kidd? If not, you are in for a treat.

Near as I can tell, the first published source proposing the theory was Fred Buchanan in the June 1989 Sunstone magazine. In “Perilous Ponderings,” Fred Buchanan talked about how a chance encounter with the word “Moroni” in an atlas developed an off-and-on interest about a possible connection between the town, located in the Comoro Islands, and Joseph Smith. After ruling out several avenues, Buchanan stumbled upon one that seemed plausible:

My friend had written and mentioned that the famous buccaneer “Captain” William Kidd, who is reputed to have hidden gold and treasure at Gardener’s Island, New York, and in a variety of New England locations, actually visited the Comoro Islands during his voyage to East Africa… Ultimately I found that Kidd actually spent a considerable amount of time in the vicinity of the Comoros between March and August 1697, and that the islands were an important stopping-off point on the long voyage from New York to India. In fact, New York was a major source of supplies for pirates in business in the Indian Ocean. Captain Kidd, buried treasure, Comoro and Moroni-Joseph Smith, treasure hunting, gold plates, Cumorah and Moroni? Is all this coincidence or is there a connection between the activities of a Scottish buccaneer in the Indian Ocean in the late seventeenth century and the development of a prophet in upper New York in the early nineteenth century? Did Joseph Smith have access to accounts of Captain Kidd’s exploits, which became more and more elaborate in the years following his hanging in London in 1701? Did accounts of Kidd’s rendezvous at Comoro and Moroni color the folklore about Kidd’s buried treasure to which young Joseph may have been exposed?

Many years later, Ronald V. Huggins published an article in Dialogue exploring the connection between Captain Kidd and Joseph Smith. The focus of that 2003 article, “From Captain Kidd’s Treasure Ghost to the Angel Moroni: Changing Dramatis Personae in Early Mormonism,” was early historical accounts describing the angel Moroni as a “murdered treasure-guardian ghost particularly (though not exclusively) associated with the story of Captain Kidd’s treasure.” Related to Huggins’ discussion was the importance of the Comoro Islands in pirate lore.

In those days pirates, even famous ones, were no oddity in the Comoros. Anyone who read, for example, the popular two-volume A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates (1724 and 1728) by Daniel Defoe (a.k.a. Captain Charles Johnson), would find the Comoro Islands figuring into the accounts of Captains England, Misson, Tew, Kidd, Bowen, White, Condent, Cornelius, Howard, Williams, Burgess, North,1 and la Bouche.2

The pirate to whom Defoe dedicated his first chapter, Henry Avery (Every), also had a connection with the Comoros, which the author fails to mention.3 There were other pirates not treated by Defoe such as William Ayer, Captain Quail, John Ap Owen, Thomas Harris, William Cobb, and Davy Jones—all famous pirates who visited the Comoro Islands at one time or another.4

Huggins also posited an association with the name Moroni in the Comoro Islands as source material for Joseph Smith.

For Mormons, the fact that the pirate was hanged for crimes allegedly committed in the vicinity of Moroni on Grand Comoro is significant because the hunt for his treasure came to play a part in the story of Moroni on Comorah.

In 2013, Jeremy Runnells took up the Captain Kidd/Moroni/Cumorah mantle in his infamous CES Letter.

“Camora” and settlement “Moroni” were common names in pirate and treasure hunting stories involving Captain William Kidd (a pirate and treasure hunter) which many 19th century New Englanders – especially treasure hunters – were familiar with.

Let’s start with Runnells and work our way back. First, he declares that “Camora” and “Moroni” were “common names in pirate and treasure hunting stories involving Captain William Kidd.” How could we test this? Well, there’s the original transcript of Captain Kidd’s 1701 trial, published multiple times in the 18th and 19th centuries, but neither Moroni nor Camora (or any derivatives) show up in those proceedings. There’s Washington Irving’s 1824 short story, Kidd the Pirate, but that doesn’t have any words like Camora or Moroni (or any derivatives). There’s some fascinating detail in the 1830 Annals of Philadelphia account of Captain “Kid”, including many tales of his treasure supposedly hidden in the Northeastern United States. Unfortunately, no mention of Camora or Moroni (or any derivatives), but it was a year too late for the Book of Mormon, anyway.

So, where did Runnells get this idea that “Camora” and “Moroni” would be easily found in early 19th century accounts of Captain Kidd? Well, it makes sense when you look at what Huggins argued in 2003. Huggins said that the Comoro Islands figured in historical accounts of a host of infamous pirates, including Kidd (and if the Comoros Islands were prevalent, obviously the capital city, Moroni, would show up as well, right?). As proof, Huggins offered the “popular two-volume A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates (1724 and 1728).” Fortunately, these volumes are easily available online (Vol. 1 here, and Vol. 2 here). The first volume (426 pages) doesn’t have a single mention of Moroni or Camora (or any derivatives). The second volume (413 pages) has one mention of “Comaro” – yay! But no mention of Moroni. Hmm…

Oh wait! We missed Huggins’ footnote! Here it is:

The edition used here is Daniel Defoe, A General History of the Pyrates, ed. Manuel Schonhorn, (Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina, 1972). Johanna is mentioned in the accounts of Captains England, 118, 130, 132; Misson, 407-16; Tew, 424-26; Kidd, 443; Bowen, 461; White, 478; Condent, 584; Cornelius, 605; Williams, 503; Burgess, 510; and North, 516. Mayotta is mentioned in the accounts of Captains England, 118; Bowen, 461, 478, 481; White, 478, 481; Howard, 493; Williams, 503; and North, 516, 521, 539. Mohilla is mentioned in the accounts of Captains Misson, 407-14, 416, 418; Kidd, 443; and Williams, 503. Comoro is only mentioned in the account of Captain North, 516.

Obviously Huggins meant that you’d find the names of the other islands making up the Comoro archipelago (Johanna, Mayotta, Mohilla) in pirate stories, not the name of the archipelago or the namesake island Comoro/Camora. Silly Jeremy. And silly Grant Palmer: “Both the Camora/Comoros Islands and the two Moroni place-names, were commonly associated with pirates and treasure hunting ventures in that part of the world—the very area of Captain Kidd’s greatest adventures.”

But it doesn’t matter, right? Because, as Huggins argued, “the pirate was hanged for crimes allegedly committed in the vicinity of Moroni on Grande Comore.” Except… he wasn’t. Captain Kidd never set foot on the large island Grande Comore, the location of the modern-day capital city Moroni. Which is why it’s a problem when Buchanan was talking in 1989 about Kidd’s “rendezvous at Comoro and Moroni” influencing Joseph Smith.

But we know Captain Kidd was on the neighboring islands of Johanna and Mohilla (based on testimonies given in the 1701 court case). So, obviously, we can count the crimes committed on those islands, right? Except… Captain Kidd never committed crimes on those islands. He wasn’t a pirate when he was in the Comoro Islands.

A History Lesson

Captain Kidd was Scottish-born but lived in New York. He was a successful privateer who typically worked the West Indies. An upstanding British citizen, he got hired in 1696 to go after pirates in the East Indies (and French merchants, because England and France weren’t on good terms). He and his crew were to be paid from the spoil they got, with a portion going back to his sponsors. Hiring these privateers was a way the British government could supplement their navy to look after their interests on the high seas… and have plausible deniability if the privateers ever did anything stupid.

With a brand-spankin’ new ship and a bunch of experienced New York seamen, Kidd made his way to the East Indies. It took a year, but Kidd and his crew finally reached Madagascar, a known pirate haven, in January 1697. Unfortunately, he couldn’t find any pirates. Whoops. After a month he headed over to Johanna, the most popular island in the Comoro archipelago. He spent March and April in the Comoros, bouncing back and forth between the islands of Johanna and Mohilla. On Mohilla he lost fifty men to sickness. Luckily he got more men on the island of Johanna and was finally able to borrow enough money to repair his debilitated ship. He left the Comoro islands an honest man, a little financially desperate, but an honest man. It wasn’t until a few months later things started to get a little fishy.

Kidd traveled about a thousand miles north to Bab-el-Mandeb at the mouth of the Red Sea and unsuccessfully attacked a fleet in August 1697. So he decided to try his luck on the Malabar Coast, along the Western coast of India. His crew grew antsy, and they attempted mutiny when Kidd refused to attack a Dutch ship. The leader of the mutiny, William Moore, later died when Kidd threw a bucket at him (this death became important later). Ultimately he only ever took two French ships while sailing down India’s western coast, but the second, the Quedagh Merchant, was laden with valuables. Unfortunately, England was on better terms with France, so the capture of the ships was viewed as scandalous (turns out the latter ship was captained by an Englishman – double whoops). Once word of these activities reached London in late 1698, William Kidd was declared a pirate and orders were given to apprehend him.

Captain Kidd, unaware of his infamy, sailed the Quedagh Merchant to the Caribbean (after a brief, uncomfortable encounter with a real pirate at Madagascar). Upon his arrival in the West Indies, he used part of his treasure to purchase a new ship and left the Quedagh Merchant, now a liability, behind. Later Kidd’s crew pillaged the ship and burned it. The remains of the Quedagh Merchant were re-discovered in 2007, just off the coast of Catalina Island.

Kidd sailed up to New York to appeal to higher ups and hid a bunch of his treasure on Gardiners Island (fueling rumors that he or his associates were also burying treasure in other areas of the Northeastern United States). He was apprehended and taken to England. Found guilty of piracy and the murder of William Moore, Kidd was executed in 1701 with two associates, and his body was hung for three years over the River Thames to discourage would-be pirates.

From this history, we can see why Captain Kidd’s time in the Comoro Islands wasn’t typically emphasized in his pirate exploits. It was inconsequential to the main storyline. In both Washington Irving’s short story of Captain Kidd and the 1830 historical account in the Annals of Philadelphia, neither Johanna or Mohilla (the Comoro islands Kidd did visit) were mentioned at all.

Unfortunately, “carefully worded statements” made by proponents of this theory tend to distort the relationship of the Comoro Islands to Captain Kidd’s more infamous exploits. Besides the quotes from Huggins and Palmer above, there’s this from Jeremy Runnells:

Captain Kidd spent considerable time in the Comoros islands and the Indian Ocean between 1697-1698 seizing booty from the French and other ships. Shortly after Kidd returned to New York in 1699, Kidd was arrested for killing one of his crew members by the name of Moore. He was also arrested for capturing a treasure ship called the “Quedagh Merchant” in the Indian Ocean near the Comoros islands.

Kidd captured the Quedagh Merchant near the coast of India, thousands of miles away from the Comoro Islands.

And then there’s the buried treasure thing. Even though it’s known Captain Kidd was poor while he was in the Comoro Islands (remember, he had to borrow money to repair his ship), some people suggest he may have buried large amounts of treasure there (see here and here). He was burying treasure before he ever acquired any treasure. Makes perfect sense.

What about Moroni?

People are right that the Comoro Islands sometimes went by variations like Camora. Noel Carmack demonstrates this quite adeptly in his 2013 Dialogue article, “Joseph Smith, Captain Kidd Lore, and Treasure-Seeking in New York and New England during the Early Republic.” He put together an impressive list of geographic references from maps, atlases, textbooks, etc. However, Carmack admits in his conclusion,

That Joseph Smith Jr. had pre-1830 knowledge of the East Indian Ocean pirate haunt—the Comoro Island group and its sultan town, Moroni—is difficult to conclusively determine. No extant pre-1830 chart or map shows Moroni as a place name on the larger island.

Carmack did present a 1778 map of Grande Comore island showing the town, but it was spelled “Moroon” (p. 93).

There’s a good reason Moroni wouldn’t often appear on maps, though. The bay wasn’t safe for European ships, at least through the mid-19th century. Here’s a description from 1852’s The India Directory:

Excepting the anchorage at the N.W. end, the island is generally steep, having no soundings at a small distance from the shore; there are, indeed, two small bays, called Ingando and Moroon, to the northward of the S.W. point, where the bottom is coral, and the depth 35 fathoms within a cable’s length of the breakers; but no vessel should anchor there, more especially as a reef of breakers is said to extend from the S.W. part of the island to a considerable distance, with shoal coral patches beyond the breakers, upon which a ship returning from Bombay to England a few years ago was nearly lost.

Remember that one reference to “Comaro” in the two-volume trove of pirate stories? This is the complete story of that exploit by Captain Nathaniel North:

They cruiz’d among the Islands, landed at Comaro, and took the Town, but found no Booty, excepting some Silver Chains, and check’d Linnen.

Yep, one sentence. That’s it. What’s the “Town”? It’s King’s Town on the northern tip of Grande Comore island, now Mitsamiouli, the only safe anchoring spot at the time (see King’s Town noted on Cormack’s map on p. 93). Unfortunately, water is hard to access on this island, so even that harbor wasn’t an attractive “refreshment” stop for European ships, pirate or not.

The Comoro Islands were indeed heavily utilized by pirates, though. They were a part of the Pirate Round, a “sailing route followed by certain mainly English pirates, during the late 17th century and early 18th century.”

From Madagascar or the Comoros, a number of profitable destinations were available to pirates. Most important were Perim (a.k.a. Bab’s Key) or Mocha at the mouth of the Red Sea. This was the ideal position for intercepting and robbing Mughal shipping, especially the lucrative traffic between Surat and Mecca, carrying Muslim voyagers on the Haj pilgrimage. Other pirates struck toward the Malabar and Coromandel coasts to rob Mughal merchants or richly laden East Indiamen.

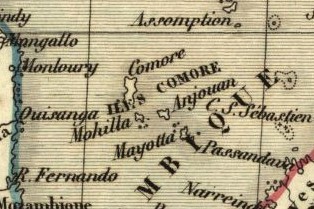

But, to be clear, the pirate stories don’t refer to these islands as a group (Comoro Islands) in any way, even though gazetteers, atlases, and textbooks of the time period will. In pirate tales, the individual island is always referenced by name: Johanna, Mohilla, or Mayotta. Maps are a mixed bag. Comoro (or it’s variations) will refer to the whole group and/or the big island. The latter is the case on the 1808 map that Jeremy Runnells insists shows Comora as referring to the whole archipelago. It’s not. It’s just referring to the one island, and you can tell because it’s the same size as the names Johanna and Mohilla.

Of the four islands, Johanna was utilized the most by European ships. It had several good anchoring spots, readily accessible water, and the inhabitants were generally favorable towards Europeans. Mohilla and Mayotta were used less often, though still way more than the island Grande Comore. A historian once wrote that the lagoon at Mayotta was a common pirate hideout.

Johanna is also noteworthy for our purposes because it contains a village named “Meroni” or “Merone” on maps from the mid-1700s. I’ve only included a 1748 map below, but the FairMormon site has one from both 1748 and 1752. (FYI – there are two legitimate 1748 map versions out there – one has “Merone” and the other has “Meroni”.) Some people have put forward this village on Johanna as a more likely source for the name “Moroni” than the town on Grande Comore. The problem is these maps are the only known reference to that village.

The island Johanna, Nzwani in the native tongue, was also historically called Anjouan or Hinzuan. In 1791, The Scot’s Magazine published a lengthy account of one man’s visit to the island in summer of 1783. It is BY FAR the most detailed account of the island I’ve found in the 18th or 19th centuries (well over a dozen pages divided in three sections), but even that only lists the names of a few towns on the island: Matsamudo, Bantani, Domoni, and Wani. Wani (spelled Ouani today) is clearly the same village as Warne in the upper right-hand corner of the 1748 map, adjacent to our Meroni/Merone. Lamude is a large town, which means it must be the modern-day Mutsamudu. When you look at a satellite map of the area today, you can clearly see the anchorage point (a dock). If Meroni/Merone really existed just northeast of the anchorage point, it has clearly merged with the current town Ouani.

From what I can tell, the only way Joseph Smith could’ve known about the village of Meroni/Merone on the island Johanna is through those few detailed island maps created in 1748 and 1752. Pirate stories, travel accounts, gazetteers, directories, atlases – none of them mentioned the village.

So, what do you think about the Captain Kidd theory? Do you believe Joseph Smith used the Comoro Islands as source material? Why or why not?

Interesting post. Thank you for putting it together.

As it happens, just this week I finished reading the recently published biography of Joseph Smith’s early years by the late Richard S. Van Wagoner: Natural Born Seer, Signature Books. He mentions Captain Kidd and covers some of the same ground cited in this post. Nothing conclusive regarding the specific name connections. Still, there seems to be a useful amount of contemporaneous source material, of the anecdote/affidavit variety, regarding this subject. Using that, Van Wagoner demonstrates that both Josephs Smith, Jr. & Sr., displayed an active interest in Captain Kidd’s legend and treasure hunting in general. The Smiths also had a close connection to seafaring culture and storytelling through Solomon Mack, Joseph’s grandfather. Also worth mentioning is Joseph’s boyhood time spent convalescing in coastal Salem, Massachusetts.

For interest’s sake, I’ll quote this from Van Wagoner’s footnote on the subject: “The Hill Cumorah, where Moroni’s father Mormon reportedly hid the golden plates, is consistently spelled ‘Camorah’ in the first (1830) edition of the Book of Mormon.” (Note 53, pg. 185) Absent any inarguable connection, I still find the name similarities both remarkable and unmistakable. Well before I ever heard anything about Captain Kidd’s legend overlapping with Joseph’s learning, Comoros and Moroni caught my eye on a world map. I’m not aware of them being common names in any other context.

Thing is, Moroni was spelled “Moroon” in both cases of 18th/19th century sources cited (the map in Carmack’s article and the 1852 sailing directory). If spelling is that big of a deal, then a source like the Moroni surname in Italy would technically fit better: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moroni_(name)

Like I said in the post, the various spellings of Camora totally work, but you’d have to argue that Joseph was getting this from either maps or geographic publications or his experiences with seafaring culture – the name just doesn’t come up in the pirate stories often enough for me to buy the “Joseph was really into Captain Kidd dime novels” argument.

It is this type of analysis that is missing in the dialogue between church publications and critical publications. Even the apologetic literature misses this. Thanks for this analysis.

Slightly off topic. The amount of misinformation is frustrating when it comes to analysing what is correct and what isn’t. The CES letter raises interesting issues but it is so biased it is hard to take seriously. Conversely apologetic literature is just as biased on the other side. The other issue is that everyone seems to look for quick criticisms and/or quick answers that you end up either defending the church or being critical of it. These types of in depth analyses of the issues provide the nuances that are needed to make intelligent decisions that, in many cases, effect people’s lives and salvation.

Well done, Mary Ann! This is by far the most extensive and detailed treatment I have seen.

I searched my email and found the below expression of an opinion from 2005:

I think it is indeed a coincidence. I’ve known about

this argument for 8 years, and I have yet to see any

documentary evidence to suggest Joseph got these names

from the Comoros Islands. Grant’s little piece below

doesn’t change that. If Joseph read a book that

references these names, he needs to quote the primary

source (IE the book). How often were the names used

in the book, in what forms and in what contexts? I

presume, since he does not provide such quotes, that

they do not exist (although if they do I would very

much like to see them and would be happy to be

educated on the subject).

I want to see mention of the name Moroni and the

Comoros Islands in Joseph’s information environment in

a way that would have been accessible to him. They

should make some sort of an appearance in newspaper

articles, letters, journals, books, or something.

Absent that, this is a curious and interesting

coincidence, but a coincidence, nonetheless. I would

sooner see the Rennaisance painter Moroni as a source

for the name than the Moroni of Comoros (also, it is

my understanding that Moroni did not become the

capital of Grand Comoro until later in the 19th

century, which underscores the need for actual

contemporary documentary evidence before we accept

such a flight of fancy).

Just my opinion, of course.

I sympathize with Runnels who seems to have trusted Palmer.

Palmer? Not so much. If he was doing real research he would have the same materials this essay used.

Good to see primary research work.

Kudos.

Excellent balanced analysis, Mary Ann .

Anyone else notice a double standard?

Comoros and Moroni on pirate maps => a coincidence

NHM in Arabian desert => Nahom in BoM

It is all pretty shaky, who to believe?

Burden of proof? Outrageous claims require compelling evidence.

Mike, a lot of people like to make the comparison to Nahom. Personally, I side with the apologists on that one, because Nahom in Book of Mormon, encountered along trail south, where Nephi & friends buried Ishmael circa 600 BC —> Nahom along major spice trail from Jerusalem, with massive burial ground used by travellers, and archaeology placing the name back at the right time period. For the Moroni/Comoros argument to work, I’d want to see an individual (not an obscure bay) named Moroni burying treasure on Grande Camore – that, to me, would be a comparable level of correlation. It’s one reason I was willing to play around with throwing historical supports to the Vernal Holley theory in my post a couple weeks ago – it’s a comparison of place names and geography to place names and geography, apples to apples. The major flaw to me of the Comoros theory is the obscure bay (Moroon) or village (Meroni/Merone) being converted to a person – apples to oranges.

I am a semi active member who does not believe in the historicity of the Book of Mormon. I see too many anachronisms. That being said, I am suspicious Joseph pulled names from Captain Kidd. Kudos to May Ann for a very thorough analysis.

the various spellings of Camora totally work, but you’d have to argue that Joseph was getting this from either maps or geographic publications or his experiences with seafaring culture – the name just doesn’t come up in the pirate stories often enough […]

I’d want to see an individual (not an obscure bay) named Moroni burying treasure on Grande Camore

I think that this is called “Moving the Goalposts.”

Like, you’re not looking at the available evidence and figuring out the most likely explanation for it. You’re saying “well, it doesn’t look exactly like how it appears in the CES Letter, so I think this is all just a crock.”

And I mean, I get that for you “the available evidence” includes your testimony. I get that it includes all the positive spiritual experiences you’ve had, especially when they were closely tied to the LDS church. I don’t place zero value on all that, and I’m pretty sure you don’t either.

I’d just like to bear my testimony that when I realized that there was no way that Mormonism’s specific truth claims held up, I prayed one of my most desperate prayers, not even knowing who was on the other end of the line anymore. And I felt what I used to call the Spirit, so strongly. I knew that they were still there, and that changing the way that I saw the world was scary but that they would be there for me as I went through this. Just like they always had.

I’d like to further bear my testimony that these feelings of closeness to Deity are natural, that a lot of (but not all) people have them, and that they are okay to have. The only way they become bad is the same way our other feelings become bad; when someone tells us that they mean we need to buy something, hurt someone, or believe everything that someone else says.

Those feelings, that closeness to God, is what really brought me out of the LDS church. Because as I learned more and more about what our LGBT+ siblings go through, I realized that it was tragic what we’d done to them, and what we taught about them. I prayed and asked Heavenly Father if this — all this that I’d learned about people’s suffering — was really how things were supposed to be. And the answer I got was a careful, measured silence, which I now know is because they’d known all along that this wasn’t right. They were just afraid that by telling me that, they’d make me more defensive, and get me to double down on rationalizations instead of realize this stuff for myself.

I’m very, very sorry if my earlier comments made you more defensive. And I’m sorry that they were so glib.

Well done MaryAnn. Anyone who believes Joseph got names from Captain Kidd clearly isn’t looking at the evidence, and is just looking for a reason to disbelieve. There may be good reasons to disbelieve, but this theory isn’t one of them. It’s laughable.

I wasn’t actually looking for reasons to disbelieve, by the time I got to the point that I considered maybe this stuff had merit.

I had come to the sickening realization that the LDS church as I knew it was hurting innocent people, that I was paying for this with my tithing and vocal support of it, and then I had no way to effect any change. At that point I was like “but it’s still the true church … right?”

” … oh. I guess not.”

Sure Jewelfox. I think the LDS Church has been cruel to singles, gays, blacks, sexual assault victims, etc. If a person wants to leave the LDS because of that, I understand, and can empathize.

But saying that the Captain Kidd theory has merit is clearly false. Reason #1 (cruelty) is fine. Own it. Reason #2 (Captain Kidd) is clearly without merit. Don’t glom on to that as a reason, because that is demonstrably false.

It sounds like you’re conflating issues. If you want to disbelieve the LDS Church, that is your right. But have valid reasons. Spaulding Theory, Captain Kidd are bad theories and easily debunked. Don’t glom onto those reasons. If you do, it sounds like you don’t have valid reasons, and are relying on sketchy information that is easily debunked.

But you’ll find no argument from me that the LDS Church has been cruel to blacks and gays. That’s demonstrably sad, but true.

Jewelfox, the Holley post and this post aren’t about debating the truthfulness of the church, they are about debating the merits of these theories. This is the type of research *I’d* want to see if I were encountering these ideas for the first time. I’d want to know the pros and cons, and I’d want to have access to whatever source material was available so I could make a judgment for myself rather than just trusting whatever the blogger said.

Say I was given an assignment – I had to write a paper defending either the Holley theory or this Captain Kidd/Comoro/Moroni theory. Hands down, I’d choose to defend the Holley theory. Based on my research, I just don’t think the pirate stories *only* theory holds up (and that is what Runnells specifically argued in his Debunking Fair piece – that Joseph *wasn’t* looking at maps, he was getting the names Camora and Moroni from pirate stories). I think, in this case, moving goalposts to include maps/geographic literature (or personal seafaring accounts from Mack family members) is a *smart* move for someone wanting to prove a connection between the Comoros and Joseph Smith. Again, though, the sticking point to me is the name (not easily accessible) and concept (geographic to individual) of Moroni in relation to the Comoros. I would not feel confident if someone asked me to defend this theory.

Reason #2 (Captain Kidd) is clearly without merit. Don’t glom on to that as a reason, because that is demonstrably false.

I just tossed it out there, in a comment in an earlier discussion, about how as a fiction writer it seemed really unlikely to me that Moroni and “Camorah” weren’t derived from Moroni and Comoros.

In response, Mary Ann wrote a humongous article about pirate history.

This topic is clearly important, but I’m not one of the people that it is important to.

Let me rephrase that: It was reading about the connections between BoM names and actual place names that caused an epiphany for me in 2010. I’ve read, and thought, and done an awful lot of things since then. I’ve long since moved on from “but is the Book of Mormon true?” and on to more pressing concerns like how I will survive a gender transition, whether or not I can immigrate to be with my loving partner, and how I can support other trans women creators who are making the world a cuter and kinder place.

For me personally, the name connection is a non-issue. It’s sort of like arguing young earth creationism. Where even if you point out the holes in the current understanding of evolutionary biology, that doesn’t mean “this specific God did it in 6,000 years” is a likely alternative. From my point of view, these essays about names are saying “this, this, and this would have had to happen in order for him to have known about this, and maybe not every place name was cribbed from a real world location.” And I’m just like, “okay,” because I don’t spend any more time these days wondering about the LDS church’s claims to truth and authority than I do about Answers in Genesis’.

I’m extremely sorry if this comes across as condescending or as a betrayal. I’m trying to explain why your essays aren’t having what may have been the intended effect. I’ve only continued engaging because I could tell this was very important to you, and that you were actually giving it serious thought. I hoped it would help you to talk through these issues, partly because I know it helped me and partly because your church has done an awful lot to hurt me and the people I’m close to and trying to help.

I’m very sorry if I gave you the wrong impression. I hope life treats you well. I hope anyone who is being hurt by the LDS church can escape.

Jewelfox, this was actually my reply to your glib comment: “You know, I’ve been itching to look into that Comoros Islands theory. The fact that the modern-day city of Moroni is on Grand Comoros Island but Jeremy Runnells keeps passing around a 1748 map of a different island in the group (Anjouan/Johanna) as evidence really bugs. I also haven’t seen anyone come up with a Captain Kidd publication from that era with those two place names. Just seems shoddy on the research front. Maybe that’ll be my next post.” Your confidence in the Moroni theory had piqued my interest: “plus, it seems really unlikely that that isn’t where he got those two names. I mean, really.” This post is the result of research on an interesting topic, and research is my thing. The intended effect of the essays is to get information out there for people researching these theories. If you are not interested in debating these theories or learning more about them, then you are not the intended audience.

Joseph Smith got the word Moroni by prophecy. It was the name of a very popular Nephite pasta pronounced such that it rhymes with spaghetti. Sort of parallel to Buckwheat, an nutritious breakfast cereal and also the name of a hero in the 1934 film Little Rascals which delighted me when it came out. Spanky, the other hero, does not appear in any of Joseph Smith’s prophecies, not even those on polygamy. This proves…. I’ll think of it here in a minute.

Wait a minute, an obsession with pasta… does that mean Nephites might have worshipped the flying spaghetti monster?!

Very informative. Btw, as far as the NHM argument in the comments, Nahom is different because the Book of Mormon PREDICTS that it is real history, with a variety of details etc. – while the Holley names list is the sharpshooter fallacy. In other words, Nahom is like shooting a gun and hitting a bullseye, while Holley is like shooting a gun and then going up and painting a bullseye around bullet hole.